Two Slide Cases

Clair Le Couteur

To cite this contribution:

Le Couteur, Clair. ‘Two Slide Cases.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/two-slide-cases/.

This contribution arranges a semi-random selection from the John Affey Museum’s (JAM) Warrington Collection, assembling a pair of display cases, each containing a dozen slides. It attempts what Patti Lather termed ‘transgressive validity’ – in her ‘checklist that mimics checklists’1 – by mimicking museum poetics on the OAR native web platform and Adobe’s PDF architecture. Accompanying the slides are 50–60 word labels, following the Victoria & Albert Museum’s ‘Ten-Point Guide’,2 as does this 180 word Intro Panel. A collection of seven quotations, or reference points, precedes the slides. Hidden amongst the quotations, slides, and labels are a set of invisible hyperlinks, which can be found only by tracing the pages with your mouse pointer. External hyperlinks gesture outward, to other locations on the internet, but the internal links point to views within the PDF, changing the location and level of magnification. This acrobatic spatial experience of jumping back and forth, zooming in and out, gradually diagrams our proposal: a flexible, combinatorial, associative validity – a tensile strength – relying on careful attention to details, and a cognitive, sculptural lacemaking.

NB: The present version of this contribution is only a preview, as this work was conceived as an interactive pdf piece. For this functionality, please download our full issue on the homepage and use Adobe Acrobat Reader (available here).

We aim…at two distinct objects by the use of systems: we use the artificial for becoming acquainted with individuals, and the natural as the means of combining them…Division and separation is the end of the artificial system; – to establish agreements is the end of the natural.

J. E. Bicheno, ‘On Systems and Methods in Natural History’ (1827)3

[T]he language in which I might have been granted an opportunity not only to write but to think is…not English…but a language of which I know not one word, a language in which mute things speak to me and wherein I may one day have to justify myself before an unknown judge.

Hugo von Hofmanstahl, ‘The Lord Chandos Letter’ (1902)4

This linguistics of interval and position is usually closed off by themes and titles, complex nouns that immobilise a system in a particular attitude. In this sense, explanations are modes of concealing…Placement as a grammatic concept can be extended to any abstraction…to a degree we may speak of meaning as a system of permutations, as a mathematics of placement.

Sigmund Bode, ‘Excerpt from Placement as Language’ (1928)5

There is always a moment when, the science of certain facts not being yet reduced into concepts, the facts not even being organically grouped together, these masses of facts receive that posting of ignorance: ‘Miscellaneous’.

Marcel Mauss, ‘Techniques of the Body’ (1935)6

The set of objects the Museum displays is sustained only by the fiction that they somehow constitute a coherent representational universe…that a repeated metonymic displacement of fragment for totality, object to label…is somehow adequate to a nonlinguistic universe.

Eugenio Donato, ‘The Museum’s Furnace’ (1979)7

The problem with things is that they are dumb. They are not eloquent, as some thinkers in art museums claim. They are dumb. And if by some ventriloquism they seem to speak, they lie.

Spencer R. Crew & James E. Sims, ’Locating Authenticity’ (1991)8

In itself, such a pair – an image…and a commentary…– does not represent anything new and is perceived entirely naturally, especially when we are talking about an object in an exhibition in a museum…A little different situation arises, when we arrange both a commentary and an explanation next to a painting (object) in such a way that both the first and the second form an artistic whole… being placed in the same compositional field with the object described, forming to a certain degree a new whole with it, these texts begin to radiate some new significances, new meanings. This clearly occurs, because such a pair turns out to be itself in the field of commentaries and explanations ‘pronounced’ by the viewer who examines this ‘matrimonial pair’ from the outside.

Ilya Kabakov, The Text as the Basis for Visual Expression (2000)9

John Affey Musuem & Clair Le Couteur, Roots Between the Tides, 2016.

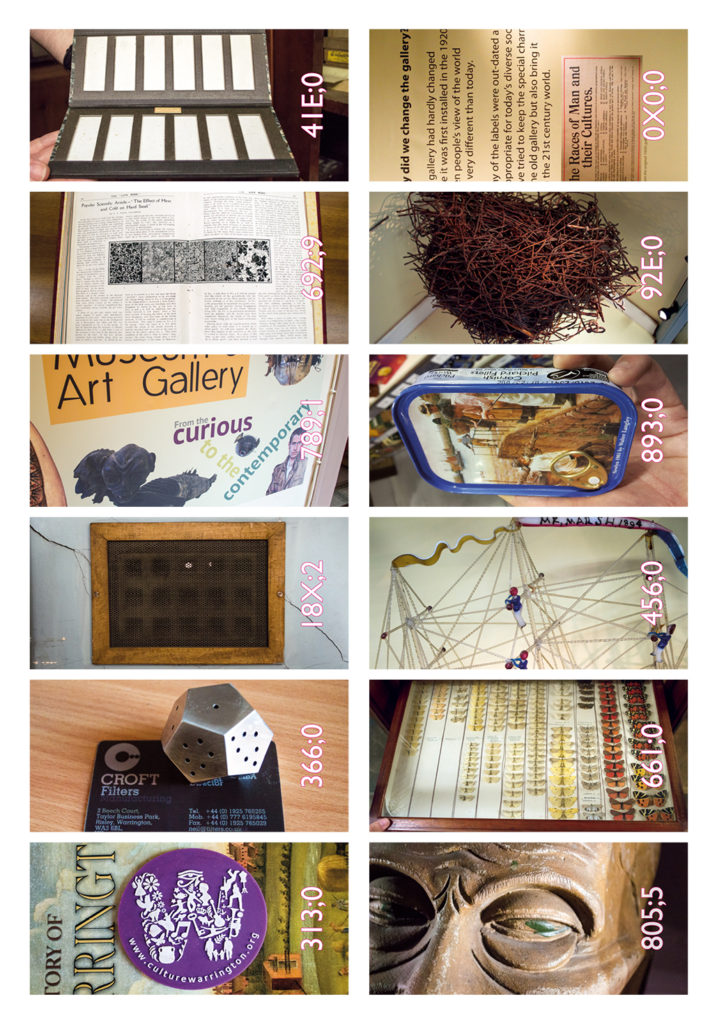

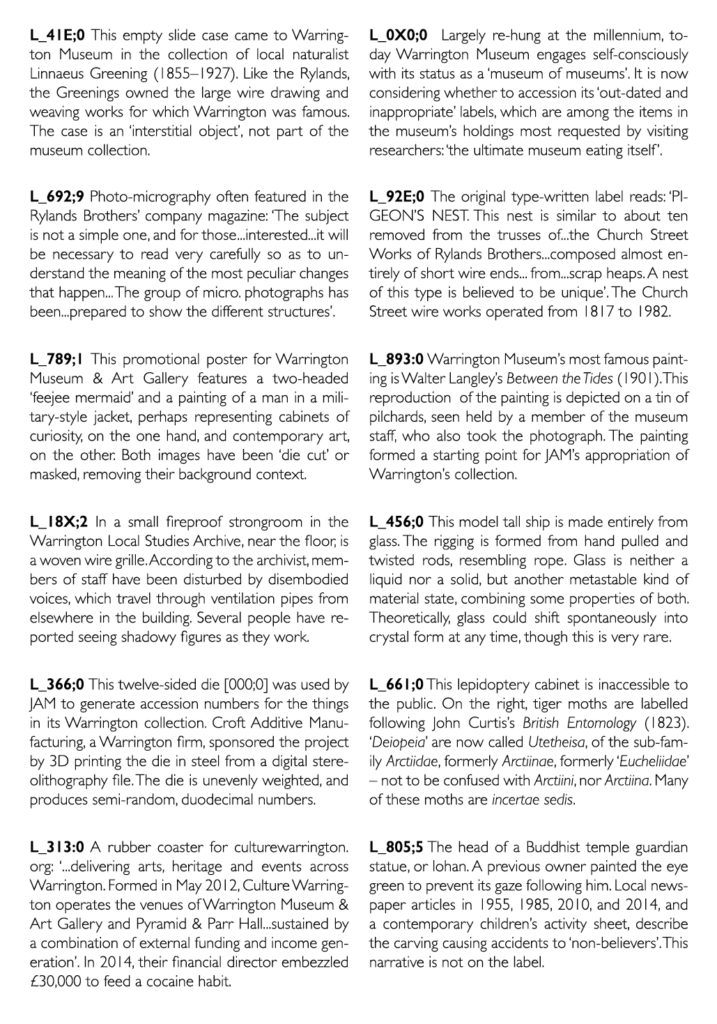

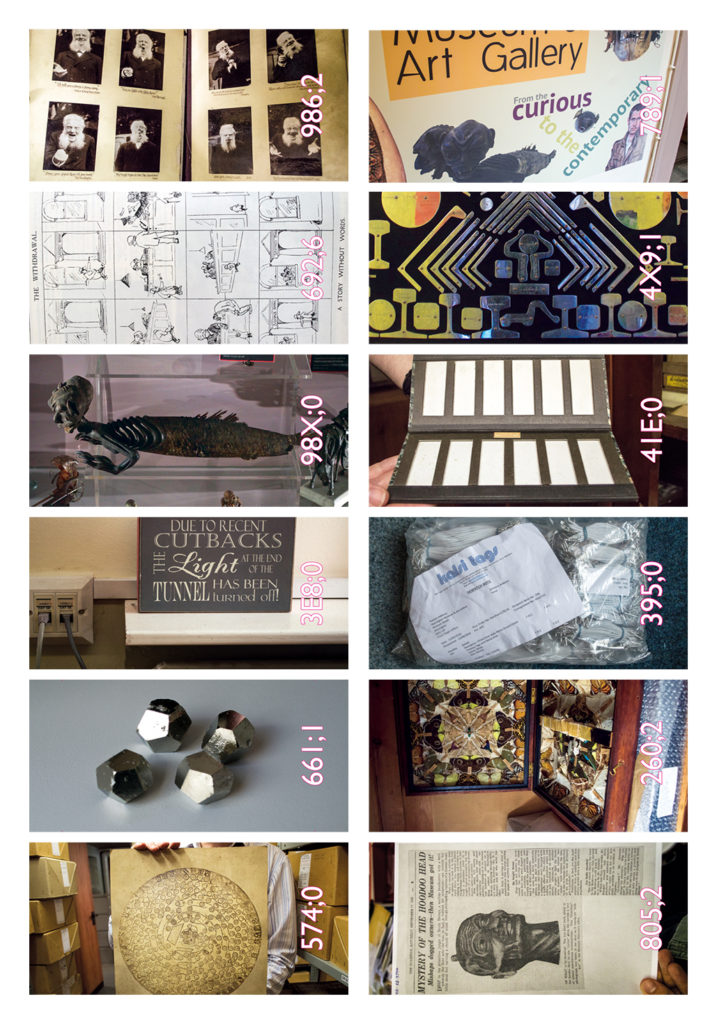

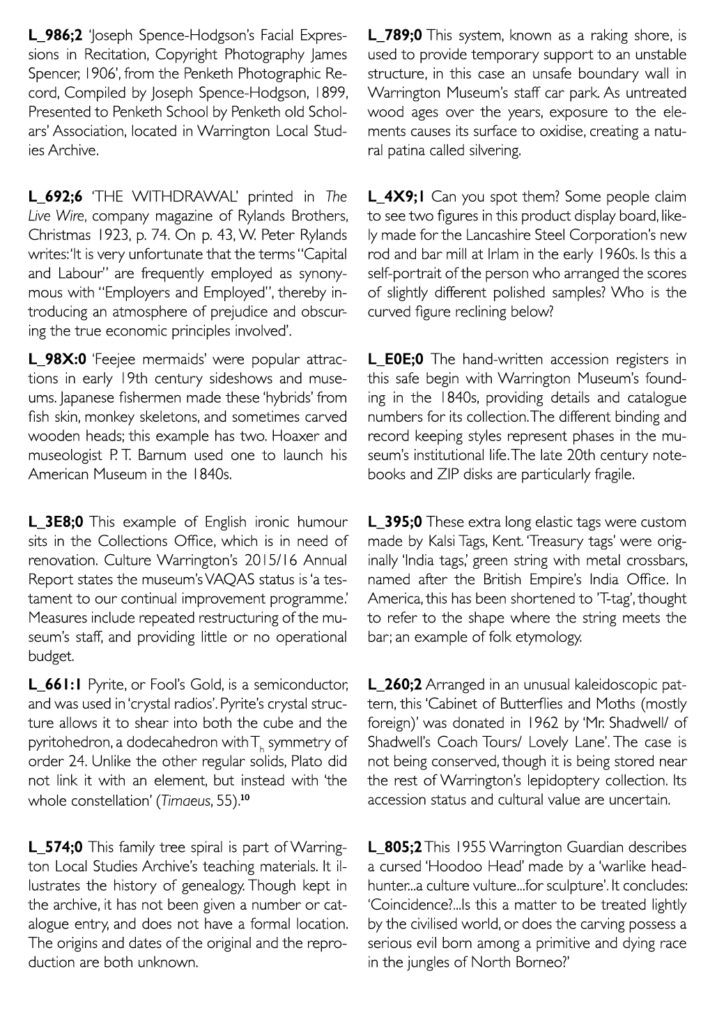

Hanging in the mezzanine void between Warrington Museum’s 1920s Ethnology room and the Fish Gallery upstairs are 188 digital photographs, linked by giant elastic ‘India tags’ [see 395;0]. The photographs were taken in the museum’s stores, archives, and surroundings, and accessioned by the John Affey Museum as part of a research residency called Roots Between the Tides (RBTT). Made for Warrington Contemporary Arts Festival 2016, RBTT is now on long-term loan to Warrington Museum. As part of the JAM accessioning process, each digital slide is given a semi-random, four digit duodecimal number. The numbers were generated by an 3D printed steel Accessioning Die – numbered 000;0 – made by a Warrington firm [see 366;0]. RBTT forms a model or portrait of the museum, a constellation saturated with tensions, a space of association. The JAM collection is not labelled in traditional museum fashion – by short, anonymous, institutionally-authored texts outside the collection – but by itself. Labelthings, linked together into one of many possible network configurations, generated from a database of virtual associations between the slides.

But how to expose these associations in detail, to map their specifics? OAR offered an opportunity. In place of the contingent gesture of elastic tagging, the virtual structures of association could be modelled with another kind of line: digital hyperlinks with the capacity to control framing. In building a cognitive sculpture of these links, between embodied minds and PDF files, we may begin to sense together that the spatial aspects of knowledge – distances, discontinuities, symmetries, the in-between of association – go beyond mere figures of speech, and instead form a vital part of the materiality of thinking.

1. Patti Lather, ‘Fertile Obsession: Validity After Poststructuralism,’ The Sociological Quarterly 34:4 (1993), 673–93, 676.

2. Victoria and Albert Museum, ‘Gallery text at the V&A: a Ten Point Guide,’ (2013), http://www.vam.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_ file/0009/238077/Gallery-Text-at-the-V-and-A-Ten-Point-Guide-Aug-2013.pdf.

3. James Ebenezer Bicheno, ‘XXIII. On Systems and Methods in Natural History,’ Transactions of the Linnaean Society of London 15:2 (1827), 479–96, 488–89.

4. Hugo von Hofmannsthal, ‘The Lord Chandos Letter,’ in The Lord Chandos Letter and Other Writings (New York: New York Review of Books Publishers, 2012), 117–28, 127–28.

5. Sigmund Bode, ‘Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928),’ in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1999), 18–21, 18.

6. Marcel Mauss, ‘Techniques of the Body,’ in Beyond the Body Proper: Reading the Anthropology of Material Life, ed. Margaret M. Lock, & Judith Farquhar (London: Duke University Press, 2007), 50–68, 50.

7. Eugenio Donato, ‘The Museum’s Furnace: Notes Toward a Contextual Reading of Bouvard and Pecuchet,’ in Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism, ed. Josué V. Harari, Vol. 699 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979), 213–38, 223.

8. Spencer R. Crew & James E. Sims, ‘Locating Authenticity: Fragments of a Dialogue,’ in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. Ivan Karp & Steven D. Lavine (Washington, DC.: Smithsonian Institution, 1991), 159–75, 159.

9. Ilya Kabakov, The Text as the Basis for Visual Expression, ed. Zdenek Felix (Cologne: Oktagon, 2000), 257.

10. Plato, Timaeus, trans. Peter Kalkavage (Indianapolis: Focus, 2001), 88–89.