Truth to Visions

Cath Keay

To cite this contribution:

Keay, Cath. ‘Truth to Visions.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/truth-visions/.

Introduction – Seed Crystal

In 1919, the Expressionist Gläserne Kette (glass or crystal chain) of architects and artists exchanged visions for advanced utopian societies living harmoniously in crystalline cities. They were led by the prolific architect activist Bruno Taut, who was convinced of the redemptive effects of architecture upon society. His iridescent Glashaus (1914) at the ‘Werkbund’ exhibition in Cologne was a celebrated synthesis of a vision shared with poet Paul Scheerbart, whose novel Glasarchitektur was published the same year. Each dedicated their work to the other.1

World War 1 convinced Taut of the necessity of an ideal for the future that was led by the arts, with architecture as the leading plastic art, capable of elevating mankind from further war, revolution, and chaos. Taut’s Alpine Architektur (1919) portfolio presented luminous drawings of coruscant cathedrals and bridges of glistening glass to provoke a collective vision so awe-inspiring that people would no longer fight. Following critical acclaim for his ‘Exhibition for Unknown Architects’,2 Taut asked fourteen like-minded exhibitors to exchange letters and designs for a better society. His first letter to the group proclaims: ‘Let us consciously be ‘imaginary architects!’ We believe that only a total revolution can guide us in our task’.3

Crystalline Growth

Throughout the sixty or so letters between the Gläserne Kette correspondents are myriad references to spontaneous growth and their aspiration to autogenetic materials. Taut asks: ‘Are you looking for the absolute, the building that grows organically?’.4

Between them, opinions diverged between those who urged for spontaneous intuitive design, and those inspired by natural growth patterns and the orderly logic of lattices.

Was their architecture buildable? In 1919, the materials and technology for Hermann Finsterlin’s biomorphic edifices or Wenzel Hablik’s angular accretions were unattainable. Yet, today’s spiritual descendants of these ‘crystalist’ architects create biomimetic explorations in synthetic biology to enable biominerals resembling limestone to be farmed from calcifying bacteria.5 Could such base morphologies be elevated to Bataille’s definition of architecture as society’s ideal nature?6

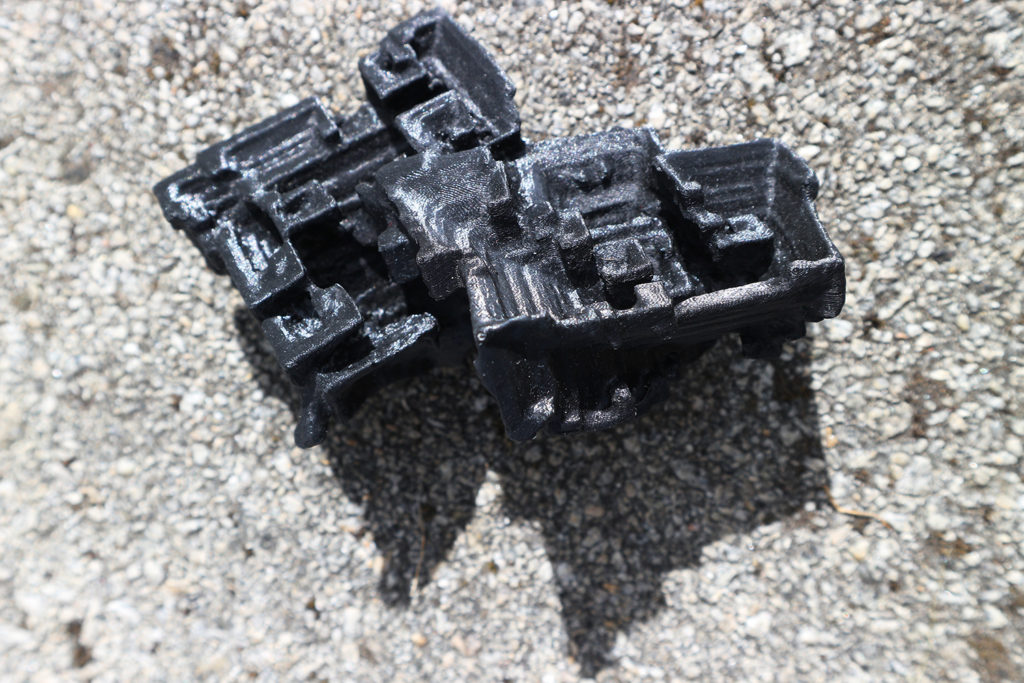

I have on my table a 3D printout of a bismuth crystal. Its irregular organic form is countered by its plasticky stratified sheen. Removed from the laboratory it becomes an alien object, a meteor from the near future collaged against shabby surroundings. Yet what if it were found in a flea market in 2119, its laminated layers matted with grime or crazed by sunlight? How can we reveal the truth of materials which are so new?

1. C. Keay, bismuth print, 2016, 10 x 6 cm, 3D print.

1. C. Keay, bismuth print, 2016, 10 x 6 cm, 3D print.

Crystal Core of the Avalanche

These architects sought to transcend the chaos and privations of Germany’s defeated, post-revolutionary flux.

The Gläserne Kette were named for their reverence for crystalline materials and forms. Their drawings are infused with sparkling, facetted constructions straddling mountains or bursting from the earth; while their writings propound transcendent visions: ‘Light bestrides the universe and comes to life in the crystal’.7

Crystals encompassed clarity and transparency; natural order and sublime beauty. The Luckhardt brothers’ architectural drawings resemble cut gemstones or quartz starbursts, while Wenzel Hablik explored the cubic forms of rocksalt and bismuth’s stepped ziggurats. In one letter, Wassily Luckhardt contemplates a crystal in his studio:

In front of me lies a crystal geode that has broken away from the earth’s crust…Doesn’t one already have the impression here of architectonic creation – don’t these structures seem to demand the creating hand of man to shape a meaningful entity out of the chaos of these elemental forms?8

While crystals symbolised the ideal, glass offered a tangible solution enabling architects to render sublime crystalline forms as glassy cubic structures associated with the Modernist movement that followed.

‘Form is initially an anchoring element, and then becomes the all-embracing crystal, the ‘world-building’.9

2. C. Keay, bismuth detail, 2016, 10 x 6 cm, detail of 3D print.

Not Crazy Caprice

Taut stated: ‘Whenever I can I will always defend the objectivity of building, as embodied for me in the concept of glass architecture’.10

Scheerbart’s extraordinary book Glass Architecture (1914) presciently proclaims every aspect of the transformative and aesthetic advantages of glass. Critic Adolph Behne wrote ‘it is not the crazy caprice of a poet that glass architecture will bring a new culture. It is a fact!’.11

Scheerbart’s influence was literally written all over Taut’s Glass Pavilion (1914) at the ‘Werkbund’ exhibition, where the architect sought to ‘introduce the effects and possibilities of glass in the world of architecture’. Fourteen rhyming aphorisms were inscribed around its exterior, and inside the pavilion their shared ‘cosmic colour love’ was realised.

‘The Glass House has no purpose other than to be beautiful’, Taut wrote in the catalogue. He then describes a tantalising list including: a tiered waterfall over lemon-coloured and luminescent red glass, silver smalti mosaics, mother-of-pearl and precious beads all illuminated by ‘kaleidoscopic images composed by artists’.

A ‘total work of art’, Taut’s Glass House was sacrificed as target practice for cadets rehearsing methods of indiscriminate destruction for the impending war.

Then as ever ‘An attack on architecture is an attack on man’.12

3. C. Keay, amber glass detail, 2016, 30 x 20 cm, detail of cast glass.

Building of a Glass House

The Wenzel Hablik Museum illuminates the town of Itzehoe in Germany’s ‘god-forsaken icy, conservative North’. It contains paintings of the galaxy, brass planets that once held sweets, starburst lights and collected crystals that Hablik carved with doors and windows into extraordinary architectures:

I was a six-year-old boy when I first picked up a rock crystal druse from the earth and faithfully looked after it for the single reason that I saw ‘magic castles in the mountains’ in it such as I wanted to build myself one day as a grown up.13

Hablik’s film scenario Building of a Glass House Beside the Sea (1920) imagines advanced technologies that spontaneously generate glass architecture from sand on a shore: ‘Magnificent structures are already appearing, giant iridescent glass domes drawn out into spikes and points – globes and tongues, spheres and flowery tubes – glittering and shining – showering out sparks’.14

New additive manufacturing techniques bring us closer to generating architecture from raw materials in situ. Indeed, habitable houses have been printed in Russia, and a white bridge in Barcelona is reminiscent of Taut’s Alpine Architecture; but a speculative colonisation of Mars by printing towers from mycelium spores now evokes Hablik’s cosmic utopias.15

BlueprintsstnirpeulB

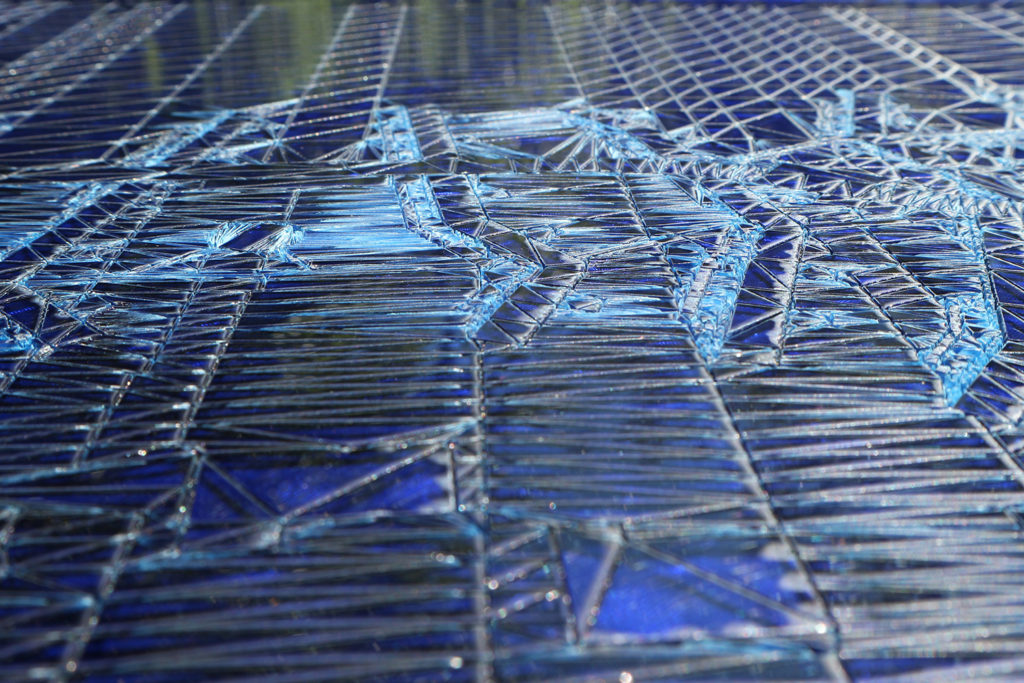

Mondfleck and myself collaborated on two print editions from his architectural scheme for row housing on a cold, remote island.

The Gläserne Kette architects used gelatin plates to duplicate their ideas for distribution round the group. Hablik’s Flower Greetings from the New World (1920) exists both as ink drawing on brown paper, and as blueprint negatives: crystalline flowers transmuted to absent white lines crazing the sky.

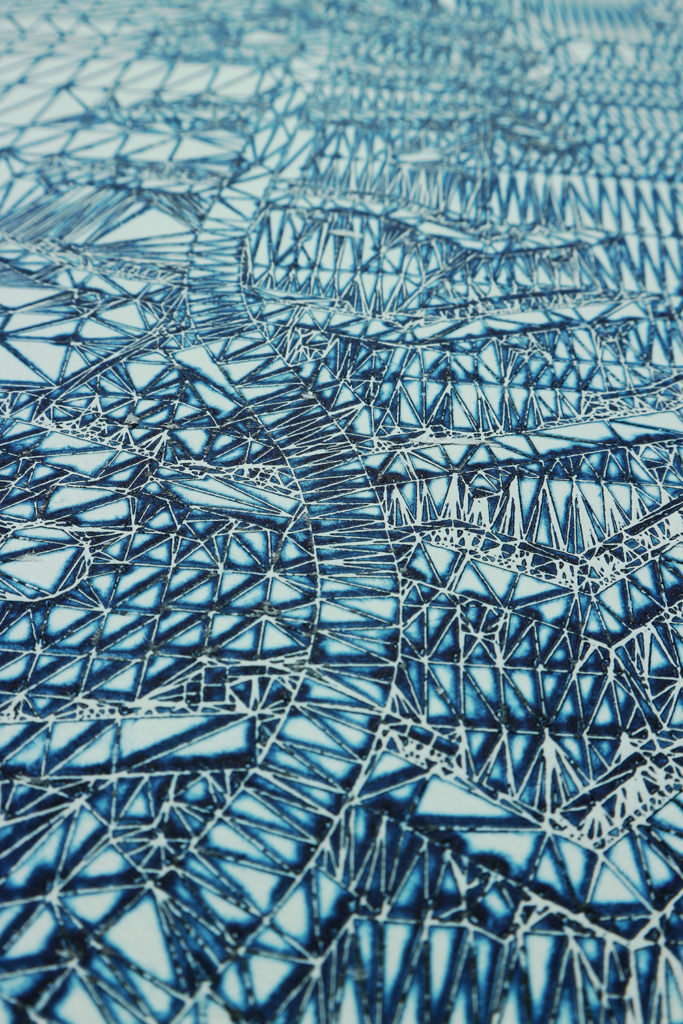

One cross-section from Mondfleck’s CAD drawing was selected from many viewpoints then lasercut onto acrylic. We produced both relief prints and etchings from this plate, and chose Prussian blue ink as the same colour as the photosensitive compounds that give blueprints their name.

Triangulated vectors lace across the relief print and cluster round buildings to form a cat’s cradle of digital information that could denote anything. The process creates texture, thin washes or fathomless velvety blue, with occasional white misprints like gulls. As an intaglio print, blue ink builds up against the cinctured lines as a snowdrift shadows a wall. This lends the print a deep, textured appearance round the edges of each inkless crevice created by the lasercutter. The result is like icy tracks recording the activities between houses on a snowy morning.

4. C. Keay and M. Paredes Maldonado, Remote Island, 76 x 50 cm, Etching.

Finsterlin’s Temple

I have here on my table a thick piece of yellow glass. Heavy as a building brick, constantly changing in appearance. Certainly its prismatic form is constant, but there is an ever-changing life in it…The vessel of the new spirit that we are preparing will be like this.16

In the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, the Finsterlin archives contain hundreds of his drawings; mostly his fantastical organic polyp architecture, but one last box contained a symmetrical building on a honeycomb plan, reminiscent of beeswax sculptures I produced in earlier work with bee colonies.

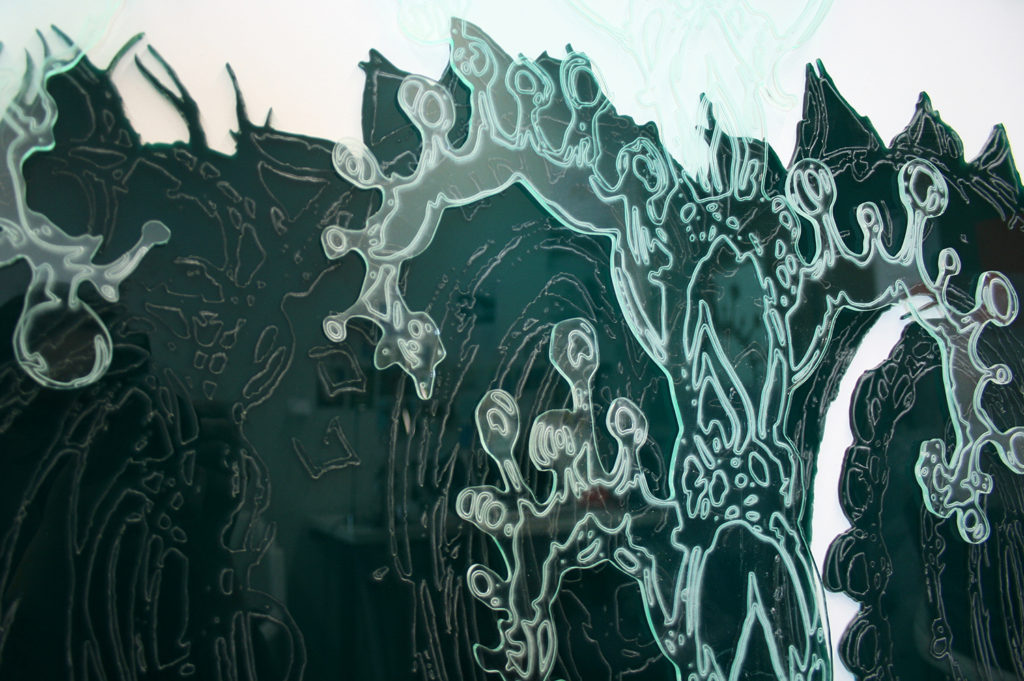

I ordered glass – thick slabs of honey-coloured bullseye.

I modeled his drawing in foundation beeswax – wax sheets embossed with hexagons that a beekeeper places into her hive. This model was cast in plaster and flint to produce a refractory mold, one that will withstand huge temperatures. The wax is melted out, the volume of the void is calculated and a corresponding amount of glass is stacked in. This brittle case is propped and levelled in the kiln to prevent molten glass breaching the mold. After firing for five days, the mold is removed and the amber glass is polished. Its prismatic form now glows on my desk.

5. C. Keay, Finsterlin’s temple, 2016

The Not-so-Distant Future

The Gläserne Kette architects believed it was their professional duty to construct a new society, to lead their country out of chaos and create one more beautiful and harmonious than ever before.

‘…a nation that lies groveling in the dust- like the German nation. Which poets feel misery so deeply as a conquered people?’17

Those who witnessed abject misery during the war, then returned home to austerity in Weimar Germany, were fired with desire for total change.

Taut wrote: ‘How good it is to have nothing, not to possess a single thing and yet always to be able to give. What do I live on? I don’t know. Someone gives me food and drink. I’ve reduced my hopes, expectations, and possessions to nothing’.18

When everything was scarce, and everybody hungry, they yearned to realise their dreams of a coming utopia. ‘I would certainly be glad to build…the kind of town that my own inner impulse suggests, planned for the people of the not so distant future, that is to say for the sort of people we can reckon with for the next 100 years’.19

As individuals living in Hablik’s not-so-distant future, my current correspondents are building from his impulse.

Remote and Anonymous

‘The individual personality will disappear with commitment to a higher task – if architecture reappears then the master builder will be anonymous…Instead the idea exists in the realms of endless joy, remote and autonomous.’20

The 1919 Gläserne Kette architects and artists used pseudonyms when exchanging ideas. Yet they would have recognized each others’ work from the Exhibition of Unknown Architects. Taut (Glas) and Gropius (Mass) were also well-known activists. Other correspondents included Bruno’s brother Max (kein Name), Hans and Wassili Luckhardt (Angkor and Zacken), Carl Krayl (Anfang), Paul Goesch (Tancred) Hermann Finsterlin (Prometheus), Hans Scharoun (Hannes) and Wenzel Hablik (W.H.)

I (Kathedral) gathered our group through contacts and residencies. We are unknown to each another but exchange work online. Snake is an animator, Lichterloh and Seven mine photographic archives, Pinnel and Medha collaborate in sound, Mondfleck, Pjeterpan and Intimator are architects, Geison is a divine solidifier of her own breath,21 Wechsel and Verwandl create digital worlds on the Atlantic shore, and I met Tellurien looking for crystals in Canada. Ei works in the realm of endless joy.

Digital footprints, however, raise a problem our forebears did not encounter, tramping under images and links we post, continually betraying our ascribed anonymity.

6. C. Keay and M. Paredes Maldonado, Remote Island, 76 x 50 cm, relief print.

Hablik’s Garden

Goal for Youth (1920) is an ecstatic scene of fern fronds, fiery fountains, and palm tree festooned with glinting fruit, drawn in ink on thin brown paper. Hablik’s fervent strokes depict spiral paths wrapping verdant plants, calligraphic blooms on fecund slopes. His gestural lines undulate along saw-tooth edges, then crisscross and fade.

His visions are persuasive, but the colours are merely suggested by script radiating from the plants, exhorting precious, iridescent pigments.

These drawings counter the versimiltude of computer graphics. And so, for a series of sculptures, I maximise the contrast between his ink and paper, to isolate then vectorise the drawn marks while maintaining Hablik’s handiwork. I seldom intervene, instead relinquishing control to the programme to decide which marks are preserved. The software overrides the artist’s intent in prioritising lines, so errors are elevated to artwork. This generative process of mutations has its own style: each side of original lines is delineated, as are flecks flung out when Hablik’s nib caught the paper. ‘…Concentrate simply on the idea that springs into our willingly creative fingers in order to be flicked somewhere into space – caught, then set free again – and the material will follow it, radiating joy. No more fears!’.22

7. C. Keay, Hablik’s garden 2, 2016

Paul Goesch – To Each His Own and to Art Its Own ‘Correctness’

After qualifying as a government architect, Paul Goesch joined Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society, and probably painted murals in the first Goetheanum, a Gesamptkunstwerk subsequently destroyed by fire. Psychoanalysis was in its infancy around this time, and Goesch’s friends experimented with these new ideas until his ‘thin-walled emotional state developed a crack’.23

His letter to the Gläserne Kette states:

the origins of Expressionism. When you learned to draw…The distorted efforts that you regularly produced were something to be ashamed of and to be hidden. But, you will discover in yourself a much higher level of creative ability than you were initially trying to develop…how the objects relate to us… This is because the subconscious, i.e. the power that enables us to create symbols, demands something quite different from an exact or well proportioned representation.24

In 1921 Goesch, delusional and schizophrenic, was admitted to Goettingen Sanatorium. He was closeted in different institutions for most of his remaining life, producing visionary drawings that were collected as ‘pathological art’. The Nazis murdered Goesch in 1940 under the Action T4 programme. His life was divided between hospitalisation and the Weimar art scene, and his art defies categorisation as either ‘outsider’ art or avant-garde.

Abandoning Ourselves to Colourful Possibilities

There were many interconnections between architecture and Weimar Germany’s burgeoning film industry.25 While little actual building was happening, there was lucrative work designing film sets, or constructing picture palaces for some architects such as Hans Poelzig. Having completed his Expressionist reworking of the interior of Berlin’s Grosses Schauspielhaus, he designed sets for Der Golem (1920). Following the success of Das Cabinet des Dr Caligari (1920), the potential of film is discussed in the correspondence.

‘Today I come to you only with a film. You’ll recognize the intention: to show the things that inspire us tangibly for once, and then the marvelous prospect of joining up in this way to work together on one project’.26

Three film scenarios are among the Gläserne Kette letters: Taut’s reworking of The Lucky Slippers, Hablik’s Futuristic Building of a Glass House by the Sea and Finsterlin’s bombastic Defiance of Salvation (all 1920), the latter deemed too flamboyant by Taut:

It is wonderfully fantastic and makes the greatest imaginable demands on the film medium…but I very much fear that the piling up of fantasy would be exhausting if the film were to be shown…I’ve suffered during some recent films, even so-called artistic ones with good actors.27

The Great Unanimity of Spirit

‘I can see the beginning of this in our tendency to join and fuse together as a first cell, without asking-who did it?’.28

The Gläserne Kette’s avowed anonymity and their method of sharing their ideas by letter, allowed them to evoke utopian visions beyond the scope of each individual. Large group collaborations and shared authorship are not typical approaches in art practice. However, these architects saw themselves as ideological descendants of the anonymous brotherhoods who constructed Europe’s cathedrals; a guild of skilled workers with a shared calling. This metaphor extended to their proposals for a quasi-sacred text titled ‘The Book’.

I have gathered an international group of practitioners (artists, architects, filmmakers) to echo their modus operandum of exchanging photostat copiesby post.29 A century of tectonic technological shifts has allowed our current chain of correspondents to communicate entirely via digital means. By adapting and extending the files others have circulated, we can then transmute our shared objectives into co-authored artworks.

‘Group work which, in its strongest form, vigorously pushes back the boundaries and limits of human activity’.30

This method of dematerialised exchange would fulfil the wildest longings of the historic group, and counters the axiom of artists as solo practitioners.

8. C. Keay and M. Paredes Maldonado, detail of print plate, 80 x 60 cm, work in progress.

Freedom from Form

Letters exchanged among the Gläserne Kette correspondents contain intriguing references to formless architectures: buildings constructed from light, clouds or fire. Were these pure flights of fancy or experimental speculations over future possibilities?

Hablik lists plans for architectonically ambitious, though not impossible, ‘futuristic projects for houses…in the quicksand, in rock (inside a mountain), and in the air (flying houses)’. 31 He further proposes a dome constructed from ‘radiant rainbows and solar rings, lunar haloes and the twinkling of stars forming the material of which the wall was built, arcs and circles crossing and intersecting’.

Such ideas were contentious. Hans Luckhardt dismissed drawings of nebulous and unbuildable things, such as Carl Krayl’s Nebelringbauten (1920), ‘mist ring buildings’, for being devoid of further contextualisation.

Bruckmann’s drawings explored ‘the architectonic value of fire…buildings that are actually glowing…built of flames’.32

As an sculptor, I have long been interested capturing formlessness, in the sense of the strange yet inevitable attack Bataille predicts on the increasingly static forms of architecture to release ‘bestial monstrosity’.33

‘Freedom from that inhibiting, burdensome struggle that ruins the most beautiful dreams of our happiest hours, when the forming hand tries to translate such dreams into reality’.34

9. C. Keay, Hablik’s garden 1, 2016

1. In the catalogue for the Glass House Cologne Werkbund Exhibition 1914, Taut wrote: ‘to the poet Paul Scheerbart, to whom it is dedicated’; and Scheerbart’s Glass Architecture states: ‘Dedicated to Bruno Taut, Honi soit qui mal y pense’. Both dedications are reprinted in Josiah McElheny and Christine Burgin, eds., Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!! A Paul Scheerbart Reader (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 101, 22

2. The ‘Ausstellung für unbekannte Architekten’ April 1919 at IB Neumann’s Graphisches Kabinett, Berlin. See: Wolfgang Pehnt, Expressionist Architecture (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1973), 89.

3. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 24 November, 1919, in The Crystal Chain Letters: Architectural Fantasies by Bruno Taut and His Circle, ed. Iain Boyd Whyte (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985), 19.

4. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 18 January, 1920, in idem, 42.

5. Martyn Dade-Robertson, Carolina Ramirez-Figueroa and Meng Zhang, ‘Radical Vernacular: Bacterial Architecture on Mars,’ Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 67 (2014): 346–53.

6. Georges Bataille, ‘Critical Dictionary: Architecture,’ trans. Dominic Faccini, October 60 (1992): 25–26.

7. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 117.

8. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, 1919, in idem, 28.

9. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 19 October, 1920, in idem, 159.

10. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 15 April, 1920, in idem, 81.

11. Quoted in McElheny and Burgin, Glass! Love!!.

12. Bataille, ‘Architecture,’ 25-26.

13. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, July 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 133. 14. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 22nd July 1920, in idem, 122.

15. Patrick Lynch, ‘This Mars Colonization Proposal Would 3D Print Biodegradable Fungus Towers that Leave No Trace,’ Archdaily, 14 February, 2016, accessed 12 October, 2017, at http://www.archdaily.com/tag/mycelium.

16. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 15 April, 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 81.

17. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, January 1920, in idem, 39.

18. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 15 April, 1920, in idem, 81.

19. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 22 July, 1920, in idem, 122.

20. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 24 November, 1919, in idem, 19.

21. ‘glassblowers, you are great, divine solidifiers of your own breath, which the deity causes to swell in all the cadences of the world-spirit’. See: Hermann Finsterlin to Gläserne Kette, Bavaria, no date, 1920, in idem, 94.

22. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 4 August, 1920, in idem, 146.

23. Sabine Hohnholz ‘“Remarkable”: Hans Prinzhorn, his collection and Paul Goesch,’ in Modern Visionaries: Scheerbart, Taut and Goesch, ed. Berlinische Galerie (Berlin: Scheidegger and Spiess Verlag, 2016), 173–78.

24. Paul Goesch to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, May 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 67.

25. Lotte H. Eisner, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

26. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 8 July, 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 118.

27. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 2 September, 1920, in idem, 146.

28. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 24 November, 1919, in idem, 19.

29. Finsterlin indicated in one letter that the group exchanged copies made using commercially available hectograph plates. See: Hermann Finsterlin to Gläserne Kette, Bavaria, 3 January, 1920, in idem, 59.

30. Hermann Finsterlin to Gläserne Kette, Bavaria, no date, 1920, in idem, 84.

31. Wenzel Hablik to Gläserne Kette, Itzehoe, 28 July, 1920, in idem, 138.

32. Bruno Taut to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, 31 May, 1920, in idem, 95.

33. Bataille, ‘Architecture,’ 26.

34. Wassily Luckhardt to Gläserne Kette, Berlin, no date, 1920, in Boyd Whyte, Crystal Chain Letters, 49.