Smoke and Mirrors: Amalia Ulman’s Instagram

Giulia Smith

To cite this contribution:

Smith, Giulia. ‘Smoke and Mirrors: Amalia Ulman’s Instagram.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/smoke-mirrors-amalia-ulmans-instagram/.

Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2017, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2017, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

When scrolling through Amalia Ulman’s Instagram account, three constants stand out: her iPhone, her body, and the many mirrors against which the latter is portrayed, phone in hand, playing a host of characters that range from kinky girl to office drone. These are the core elements of Ulman’s online melodramas, a genre that she has refined in the last couple of years with two scripted performances designed entirely for circulation on Instagram and Facebook: Excellences and Perfections (2014) and Privilege (2016). It is with these two projects in mind that the following pages investigate the nature of Ulman’s sites of research.

Using a reflective surface is obviously a practical way of taking a selfie with some depth of field. Ulman is far from alone in repeating this act over and over again, nor is she the only contemporary female artist to have been accused of being hopelessly narcissistic for it. As Sarah Gram rebutted in 2013, such an accusation demonstrates ‘an extraordinary lack of insight’ into how women can conceive of autonomy within a late capitalist economy premised to a significant extent on the exchange of enticing images. ‘Narcissism’, Gram wrote, ‘may not only be what capital expects but also demands from young girls, in order that they be legible as girls at all’.1 An influential source among artists of Ulman’s generation and orientation (call them digital natives, 89plus, post-internet or whatnot), Gram’s text strongly resonates with her performances. Excellences and Perfections and, to a lesser degree, Privilege are premised on appropriating and acting out the expectations of the audience on social media. From the outset, the idea was to turn a mirror back onto the fantasies of this public in order to expose their effects on how we (women in the specific) perceive ourselves. The bottom line being that there is no such thing as a solid, unmediated self.

In Ulman’s case, then, mirrors are more than just reflective. They are reflexive. Not just because they implicate the spectator in the picture-frame, but because they are metaphors for this artist’s belief that reality (and with it, identity) is inherently constituted as a second-degree image. Understanding the workings of the media is at the centre of this vision of the world, whereby transmission and simulation are seen to generate the only experiential parameters that truly matter. In this context, the very notion of site, with its claim to fixity and self-containment, is fundamentally unhinged.

I am reminded, no doubt arbitrarily, of Robert Smithson’s dialectic of site and non-site. Smithson originally articulated this relationship in his Mirror Displacement installation for ‘Earth Art’ (Cornell University, Ithaca, 1969), an exhibition that is now associated with the birth of Land Art. His contribution to the show was something of a mock-science project. As a starting point, he went down a local mine armed with a 35-mm camera and a bunch of mirrors, which he then scattered around the network of subterranean tunnels with the intention of taking pictures of their reflections. The gallery installation that followed consisted of a series of floor sculptures made out of mirrors and heaps of soil extracted from the mine, surrounded by photographic and notational documentation of Smithson’s underground adventure. The exhibition catalogue frames the whole project in terms of his pseudo-scientific theory of non-site. While the site is explained to be a physical landmark (in this case, the mine near Ithaca), the non-site is a negative function of the latter as it is reproduced across a multitude of technological channels (photographs, text and so on). Smithson liked to visualise this dialectic with mirrors, presenting them time and again as illustrations of the mechanism of displacement he believed to be at the heart of every act of transmission. The point for him was that the site never quite existed without the non-site, for as soon as anything is situated it is also codified and modified by language (be it visual or textual). In a sense, the non-site was always more tangible than the site itself. But what really mattered to him was the gap between the two. Smithson saw a lot of potential there, describing it as ‘a space of metaphorical significance’, or more simply, ‘a vast metaphor’. Even more important for the purpose of this article, he imagined the journey across this zone as necessarily ‘invented, derisive, artificial’.2

I am not trying to say that we absolutely need Robert Smithson (a male artist, no less) in order to understand Ulman’s work, only that he offers a suggestive way to address the theme of this issue of OAR by allowing us to reimage the concept of site in negative and fundamentally fictional terms. This approach seems much better suited to an art practice than more conventional notions of ‘site’ and ‘research site’ derived from the social sciences. Of course, Ulman’s selfies look nothing like Smithson’s earthy brand of Land Art. Still, to my mind her mises-en-scène are ‘artificial’ zones of metaphorical significance in the sense Smithson intended it. Only, for him, it was all about psycho-geography and the erosive potential of language, whilst what matters with Ulman is subjectivity and the way it is affected by images. Not long ago, she admitted, ‘I manipulate my own online presence in order to show how easy it is to manipulate an audience with images’. Her goal? To expose ‘the female body as virtual construction suffered in silence’.3 Facebook and Instagram lend themselves to exploring this dynamic because they are widely seen to be at the same time performative and immediate, spontaneous even. Not only are the performances that recently propelled Ulman onto the international stage formatted specifically for these platforms, they take social media trends and memes as their subject matter. At its most basic level, then, the site of Ulman’s research is the web. The twist is that Ulman’s work is overwhelmingly about fictitiousness: artificial situations, plastic surgery, counterfeit merchandise, fake clinics, neighbourhoods and even entire cities that are just façades. This seems like a more interesting trail to follow than simply saying that her research is primarily situated online, which it is of course. If we are to fully articulate the site of her practice, we better assume that it is something of a non-site, much like identity for her is fundamentally slippery. With this in mind, one might begin to appreciate her penchant for the absurd, the artificial, indeed the derisive.

Excellences and Perfections

A turning point in Ulman’s career was the completion of Excellences and Perfections in the autumn of 2014. The performance consists of a series of carefully crafted status updates, mostly selfies accompanied by brief epigraphs and strings of hashtags. The narrative is organised around three chapters: Innocence, Sin and Redemption. The fable they conjure is of a naïve blonde who moves to Los Angeles and, after breaking up with her boyfriend, spirals down the city’s world-famous vortex of superficial obsessions.

The homeland of Hollywood and Disney, LA, is a befitting if hyperbolic demonstration of Ulman’s belief that reality is all about façades and gimmicks. Apparently, it is why she chose to live there, because it is a non-site of sorts. Her take on the city harks back to a longstanding literary tradition that portrays Los Angeles as the ultimate hall of mirrors and, as Mike Davis put it in his inimitable study of the genre, world capital of ‘counterfeit urbanity’.4 This body of texts was at least half a century old when, in the early 1980s, the philosopher Umberto Eco positioned the Californian megalopolis smack in the middle of his ‘travels in hyperreality’.5 More recently, it was Thomas Andersen’s film-essay Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) that presented the city as a fictional construct, exploring its mythologies across an endless sequence of iconic movie sets. Excellences and Perfections can be seen to unfold in the footsteps of this lineage, to which it adds Ulman’s precocious understanding of the effects of social media on the millennial society. One could posit that if Cher Horowitz, the lead character of cult teen movie Clueless (1995), and Clay from Bret Easton Ellis’ equally popular novel Less than Zero (1985) had a post-internet child, it would be the protagonist of Excellences and Perfections. You get the picture.

1. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

1. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

The performance opens with a version of Ulman inspired by Angeleno and Asian Tumblr girls in her network. Imagine her in fluffy socks and cute pyjamas, wearing ballerinas and pretty lace dresses, or eating strawberry tarts and collecting Hello Kitty stickers (fig. 1). This first act is colour-coded on a fairly uniform scale of pink and white, hues that implicitly tag her as girly and inexperienced. Act two departs quite dramatically from this candyfloss world, veering towards a much more noir aesthetic dominated by gold and black. In the process, Ulman’s alter ego has a makeover, maturing into an escort with a sugar daddy who pays for her shopping sprees in the luxury goods department. Eventually, she gets enormous breast implants, becomes addicted to drugs, has a meltdown, and finally goes to rehab (fig. 2). It is worth mentioning at this point that isolating a colour palette is for Ulman a key step in building a fictional microcosm. Much like a set-designer or a professional retoucher working on one fashion campaign after the other, she tends to streamline the gradation of her individual projects in order to give them extra definition as discrete storylines. Another thing worth noting about her technique is that she never simply appropriates and recycles pre-existing images. Although she takes screengrabs as part of her research, she generally reconstructs what she encounters online from scratch. This gives the backdrops of her photo-shoots an uncannily curated look. Both parodies and unique fabrications, they come across as highly beautified versions of a matrix of somewhat familiar visual references.

2. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa..

2. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa..

‘I think Arte Povera, swirls, poor girls, £1 stores, money, diaries, esparto and glitter is pretty me’, the artist has said when asked about her signature style.6 Still, there is something deliberately generic about the aesthetic of Excellences and Perfections. The settings that form the backdrop to the first two acts reinforce this impression.7 Hotel rooms, lounges, airports and spas – these are globally streamlined spaces that symbolise leisure as much as transience. They are the kinds of places that tend to be defined negatively as un-homely, neutral, and indistinct. They are non-sites of sorts, just like LA itself. Robert Smithson was drawn to them precisely for this reason. Once again, the dereliction of his Hotel Palenque (1969) is at the opposite end of the aesthetic spectrum from the catalogue of polished mirrors and marble sinks one finds inside Excellences and Perfections; just as the technical sketches Smithson made for his Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport Plan (1967) have nothing whatsoever in common with the sexy look of the selfies Ulman took on airplane toilets. What matters here is not formal resemblance, but conceptual continuity. The point is that hotels, airports and planes equally belong with a poetics of circulation and endless replication.

The third and final act of Excellences and Perfections sees Ulman return, still in character, as a newly balanced individual. Fruit platters and asana poses dominate her journey to redemption, along with pious self-help cards that purport to restore balance by actively discouraging any form of action (fig. 3). This last act is tailored after Goop, a popular lifestyle blog run by the Angeleno actress-turned-wellbeing-guru Gwyneth Paltrow, and a contemporary staple of Los Angeles’s deep-rooted cult of the body. Eating ‘raw’ and sleeping ‘clean’ (as Paltrow invariably recommends) are only the latest instructions in a much longer course of collective brainwashing in the name of physical perfection. You do not have to be half as interested in the mechanics of indoctrination as Ulman is to find its global success a source of fascination. No matter how much avocado she eats, however, the heroine of Excellences and Perfections will only truly find redemption in the form of a new boyfriend. A picture of the young couple in matching bathrobes closes the performance, sanctioning her rescue by a conventional happy ending. The neat tripartite structure of Excellences and Perfections indicates that Ulman worked from a script that had a clear beginning and end. The artist eventually revealed that she had prepared all the status updates for the performance in advance, and then leaked them on her Instagram and Facebook accounts over an interval of five months (some of which she actually spent in a retreat in the Californian woods). Only at the end of this period did it become clear to her followers that they had unknowingly taken part in a prefabricated play whose contents had not been shared instantly at all, as Instagram would have it, but with a delay.

3. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

3. Amalia Ulman, Excellences and Perfections, 2014, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

Few, if any, suspected it was a hoax, in spite of precedents such as lonelygirl15 (2006–2008), a YouTube channel that went on gathering millions of views for over two years before it was revealed that its teenage protagonist (aka lonelygirl15) was not in fact a genuine user but a paid actress. Perhaps unaware of this reference, Ulman’s rapidly growing audience did not really question the veracity of her actions, being mostly divided over whether these made her into a wicked seductress or a fragile soul in need of massive outpourings of cyber-support. The stunt paid off: mainstream journalists and art critics alike commended the originality of the performance and its meticulous execution, agreeing that Ulman had succeeded in presenting a disturbing mirror image of contemporary social relations. Excellences and Perfections ‘reflects our worst anxieties back at us’, Molly Languir wrote for Elle, ‘tweaked just enough to become readily apparent, like a fun-house mirror that instead of warping the world allows you to see it more clearly’.8

Ulman later explained how she came up with the idea for the performance at a point when her online persona was being misconstrued to such an extent that the only logical way out appeared to her to be TMI (Too Much Information). A consolidated strategy among the famous, TMI involves oversharing, overtagging and overposting in order to divert attention from one’s private life. The artist squared this technique with the observation that women’s online popularity is directly proportional not only to their sex appeal, but to their fiascos too. Sometimes called Trainwreck TV, this sad form of entertainment tends to be reserved for female celebrities. Think Britney Spears and Amanda Bynes (though lately Kanye West has dominated the field).9 More often than not, their misfortunes are set in Los Angeles, feeding its already consolidated reputation as a place in which spectacle breaks humans. Armed with a Machiavellian understanding of the art of online performance metrics, Ulman took it upon herself to stage-manage the fantasies of failure that were being thrown at her anyway. In order to properly assassinate her own character, she opted for a tragically exaggerated caricature of the brainwashed narcissist. In this sense too, Excellences and Perfections is a mirror. As the artist had bet, she earned the sympathies of thousands of new followers when it became evident that she was having a terrible time.

In devising this project, Ulman went beyond using the internet as an engine for searching and sifting through data. What she did was turn its inbuilt capacity for feedback into the content of her performance. In a sense, Excellences and Perfections is a barometer of popular appetites. This is also what makes it site-specific to Web 2.0. In the early 2000s, the upgrade to this system revolutionised the online interface by allowing users to upload feedback on websites in real time. Social media are a direct product of this reconfiguration. As many have remarked in the past few years, it was a mixed blessing. Initially welcomed for allowing alternative forums to emerge from the bottom up, Web 2.0 configured a highly exploitable overlap between private and public interests. For one thing, the market jumped at the opportunity to refine its services through algorithms that use the data we input online to target our personal accounts with tailored ads and messages. And one could posit that Ulman is at home among the crowds of marketing strategists, digital trendsetters and aspiring scriptwriters that populate the shores of California. Like them, she recognised early on the potential of social media for extrapolating contemporary social typologies and feeding them back to an audience hungry for their expectations to be reaffirmed.

For Excellences and Perfections, the focus was on conventionally good-looking girls whose online presence is carefully retouched in order to appeal to a broad spectrum of followers. In choosing this crowd-pleasing meme, the artist deliberately reproduced an existing system of ratings, reinforcing a pattern of feedback that already favours impossibly normative body types. It did not escape the attention of commentators, who saw the performance as a mirror on social reality, that all this was deliberate. The point was to impersonate an idealised version of what women are expected to perform in order to excel in consumer societies (hence the title, Excellences and Perfections). As others have noted, however, Ulman’s alter ego upholds a beauty regime that is by no means a defining condition of womanhood, but a privilege that only a minority gets to be hard done by (after all, a mirror only shows what you choose to put in front of it). Aria Dean is one of many who condemned ‘selfie-feminism’ on these grounds, calling it ‘a wet dream’ for white feminists premised on a myopic replay of ‘freshman-year gender-theory-favourite Laura Mulvey’.10 The question of whether Ulman’s script falls short at this criticism is a no brainer. But then again, she is refreshingly honest about her commitment to deconstructing the dominant narratives that most people live by. If she parodies cute Asian tumblr girls, for example, it is because this is a widely exoticised fetish, especially online. Likewise, in the second part of Excellences and Perfections Ulman plays ‘ghetto-bitch’ to the sound of Iggy Azalea as a parody of white girls appropriating black pop culture.11 In a way, she is co-opting precisely the kind of solipsism Dean talks about.

Among the other characters that Ulman researched for Excellences and Perfections are Angeleno lifestyle bloggers who use their social media accounts to advertise haute couture collections in return for samples gifts. This explains why there are plenty of Dolce and Gabbana, Dior and Chanel logos emblazed on the objects that surround the young protagonist of the performance, punctuating her hungry climb among the local jetsetters. These accessories signal at once the realisation of her darkest dreams and the growing objectification of her persona. Although the artist maintains that she used counterfeit merchandise as a play on the ‘fake it until you make it’ mentality explored throughout the performance, her endorsement of high-end brands also transcends the distinction between genuine and simulated sponsorship.12 This begs the question of where Excellences and Perfections is situated within the feedback circuits that make user-generated data such a feast for big business. Without necessarily detracting from its timeliness, it is important to underscore that calling it a mirror on reality also deflects attention from the fact that its author stands to profit from actively reproducing the logic of the market.

Ulman has said that she does not want to be ironic (read: cynical) about what she portrays, so perhaps humorous would be a better way of putting it. Excellences and Perfections is full of dark humour. If act one was met with puzzlement and act two escalated the dramatic involvement of a growing audience, then act three came as a bit of an embarrassing comic relief. Obviously some took it at face value, but others clocked onto the fact that it was a parody of a Goop-ed lifestyle. Not everyone found it amusing. What is perhaps most interesting (though unsurprising) is that women understood what was going on much more readily than men: ‘LOL’, they said in a nutshell, ‘we get it, it’s funny’.13

4. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

4. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

Privilege

Just over two years after the completion of Excellences and Perfections, Ulman’s Instagram looks unambiguously aligned with the conventions of comedy and satire. This performance is titled Privilege, and features the artist playing a number of incongruous roles to comic effect. At times, she is a Pierrot, at others an expecting mother, at others still she appears on screen through bird-faced selfies, and all along she plays the part of the corporate employee who wears exquisitely demure outfits. To be more precise, Ulman refashioned herself as a Manhattan yuppie. The reference is made clear at the start of the performance with a short clip from the late 1990s HBO series Sex and the City. Styled with Miranda Hobbes’ wardrobe in mind, Ulman’s office uniform is generally topped by a pristine white shirt and finished off with low ankle-strap heels. It looks nothing like the sexy teen ware to which we had grown accustomed in 2014. In devising this act, in fact, the artist sought once again to turn a mirror on her critics, this time co-opting the accusation (which followed in the wake of the success of Excellences and Perfections) of having become a shrewd entrepreneur and social media puppeteer.14 More broadly, Privilege is a comment on how ‘online we all become caricatures of ourselves’,15 Ulman told me. It is no surprise, then, that occasionally its heroine can be spotted wearing a clownish red nose (fig. 4).

The gag went on for over nine months. During this time, Ulman gestated a fake pregnancy with only the support of her sidekick, Bob, a pigeon-puppet and a meme for whom she reserved all the best lines (including ‘what I do as an artist is I take an ordinary object—say a windshield—and, by shitting on it, transform it into something that is uniquely my own’ and the more minimalist, ‘I will shit on everything you love’, fig. 5). Judging from the comments of her followers (now approximating over a hundred thousand), the pregnancy was widely presumed to be a stunt in the style of Excellences and Perfections, but the uncertainty still managed to generate some distress among her followers. Toward the end of the performance, Ulman cleared the air by uploading a highly stylised portrait of her prosthetic belly perched sideways on a wheeled office chair. Comments ranged from the festive ‘when is that baby gonna pop out’ to the dead serious ‘you can see the line of the mould’. Of course you can. Ulman is clearly putting up a show. Why else would she clothe herself in the garb of the ventriloquist, the Pierrot, the clown even?

5. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

5. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

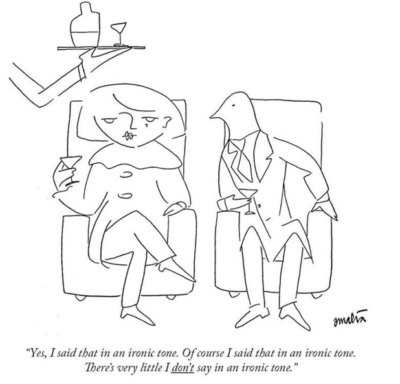

There are drawings too—great drawings in fact. Ulman told me that she made them herself, replicating the style of Charles Barsotti’s satirical cartoons for The New Yorker. The unchallenged protagonists of her parodies are Bob and Amalia, the latter almost invariably dressed in a yuppified version of the Pierrot costume. In one sketch, the two are sitting on a plane, having an argument. Martini in hand, she mocks his thickness: ‘Yes, I said that in an ironic tone. Of course I said that in an ironic tone. There is very little I don’t say in an ironic tone’. (fig. 6) Which seems like a good way of approaching Ulman’s work in general.

The couple’s surreal routine unfolds inside a small office (very nearly a large cubicle) on the seventeenth floor of a skyscraper in the heart of the Financial District. Previously the artist had used Instagram’s built-in GPS to misdirect her followers as to her whereabouts, but this time she made a point of sticking to the address displayed on her feed: Suite 1717, 811 Wilshire Boulevard, Downtown LA. Instead of anchoring her digital mise-en-scène IRL, however, these coordinates only add another layer of non-site-specificity. Let me explain. The Financial District was developed in the 1980s in an effort to compete with Wall Street and establish Downtown LA as the gateway to Asian capital. This amused Ulman, who liked the idea of working in a wannabe replica of the Big Apple. One Wilshire, a nondescript building around the corner from her studio is one of the biggest broadband hubs in the world with an underground cable network channelling one third of the internet traffic between Asia and the US. You would think an artist whose entire practice is based online would care about this, but in researching the history of the neighbourhood, Ulman became primarily fascinated with the failure of the Financial District to fully take off. ‘Half of the office suites here are empty’, she told me with a frank smile, ‘it’s all a façade’.16

6. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

6. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

Aside from this, that Ulman made a point of picking a completely unremarkable corporate suite is entirely in keeping with the figure of the artist as marketing researcher and fabricator of virtual fantasies that bank on the sinister appeal of a successfully capitalist lifestyle. ‘I work better here than in a traditional artist studio’, she told me when I visited her, ‘for the same reason I like to work in airport – it’s a neutral space’.17 More non-site than site, Ulman’s office only comes alive through the lens of her iPhone and a solid dose of digital artifice. In one, particularly striking image, the artist Photoshopped herself six extra arms, each holding a key accessory for the performance: a giant staple, a clock, a red balloon, a red mug, red scissors, and fake flowers (fig. 7). This is her own take on that staple of modern advertising in which the Hindu goddess Kali is fused with the Western stereotype of the multi-tasking mother. It is a caricature of it, too.

Like all of Ulman’s projects, Privilege is strictly colour-coded. From the outfits of the protagonist to the absurd clerical props that surround her, the aesthetic is dominated by a basic spectrum of blacks and whites injected by infusions of deep crimson and admiral blue. These are the shades of old-school corporate design, the artist told me. Perhaps; but with its quirky cast of characters her office looks nothing like the workplace of a genuine white-collar worker. Instead, it looks distinctively like one of Ulman’s synesthetic visions (she does in fact have synaesthesia, a rare neurological condition that manifests itself in the combination of two or more sense impressions, such as for example colour and language, or colour and space-time perception). Aside from Ulman’s brain, the chromatic scale of Privilege strikes a chord with the aesthetic of contemporary crime TV (think The Good Wife, a reference the artist acknowledged in passing). There is something thrilleresque about Privileg – and it’s not just because clowns can be creepy. No, it’s the colours. All that red bleeding through the grey world of Bob and Amalia feels ominous, especially in the context of a pregnancy (even a fake one). The performance does in fact end with the two in a car crash in which she loses the baby and the bird becomes a cyborg. But, even before the accident, the office had grown into an absurd crime scene, with the artist casting the most ludicrous object as clues to a larger plotline. She makes a huge deal of staples, for instance, isolating them under a spotlight like forensic specimens, and insisting that they are unmistakable evidence of something only she can see. Once again, it is about faking it until it becomes real. Or, until you lose it.

7. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

7. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

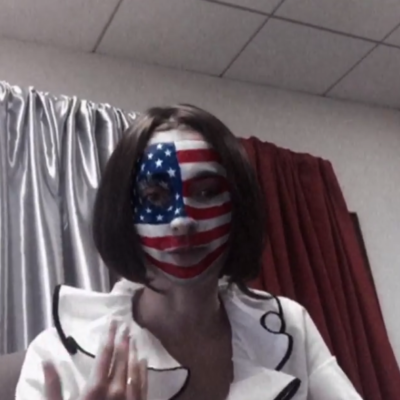

There is an additional connotation to the colours of Privilege – they match the American flag. The connection becomes salient toward the end of the performance. This has to do with the fact that, contrary to what she did with Excellences and Perfections, this time Ulman let the action unfold roughly in real time. Every day, she would go into the office, like a ‘real’ employee, and produce something for Privilege. This meant that the main plotline – the pregnancy – was gradually eclipsed by more pressing political concerns, turning into a bit of a dead end. As the 2016 campaign of the Republican candidate for president, Donald Trump, grew more hateful and his Tweets wilder in their speciousness, Ulman decided to shift the focus of the performance and prolong the original timeline so that it would end after Election Day (which explains why the pregnancy goes on for over nine months). Clearly, her intuition that online communication turns individuals into caricatures took on new meaning as the American mogul gained massive popular support (Twitter followers in the lead), in spite of his blatant disregard for conventional notions of factual accuracy and political coherence, not to say correctness. Even within his own party, many dismissed Trump as a joke, a farce. The American electorate made them eat their words.

At points, Privilege comments caustically on the news. In one post, the artist – who is originally Argentinean and grew up in Spain – targets the rise of anti-immigration propaganda with a video-portrait of her face covered in a digital mask of stars and stripes (fig. 8). Using a modified selfie app, Ulman made her features look grotesquely nationalistic. ‘You think my accent is funny’, the mask whispers in a derisive, overacted tone. ‘You think my English is cute. You called it broken English. You think I’m broken’. The accusation comes with a markedly Spanish inflection. ‘Well, wait and see. Wait until I get my papers. This baby is my anchor’. Ulman here is pretend-threatening to use the baby to obtain a green card. And although she can be seen to take a stab at Republicans and Democrats alike, Trump’s voice was the loudest in accusing illegal Latina immigrants of plotting to give birth in the US in order to legitimise their residence.

8. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, still from a digital video, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

8. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, still from a digital video, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

This is where the physical coordinates of Ulman’s office become important for situating her Instagram script in the context of dynamics occurring in situ. For the last three decades at least, many local artists and activists have directed their forces against the gentrification of Downtown LA, a historically Latino area that is currently suffering from critical levels of displacement and homelessness.18 For someone like Ulman to hire a suite right in the belly of the beast is no insignificant gesture. As mentioned before, 811 Wilshire Boulevard is located in the Financial District. It is one of a cluster of corporate towers whose dark reflective surfaces stretch skyward, breaking the pattern of low-rise warehouses that characterise the old Downtown LA past Broadway Avenue all the way down to the Fashion District. Much like the matter of financial speculation, Ulman’s pantomime of ‘privilege’ travels through the transnational circuits of digital exchange, and in keeping with the conditions of its online circulation, the corporate fantasy we are invited to follow is carefully cropped out of the urban fabric it inevitably belongs to. By her own admission, Ulman makes a parody of the ambition to become a member of the middle-class establishment in the knowledge that she is also a victim of it. While she makes a sardonic mockery of what has become of the American dream, she is not prepared to forfeit her allegiance with the capitalist aspirations onto which it rests. In the end, it is not easy to pin down the politics of Privilege, not least because it is so embedded in parody. A critic of reactionary forces, Ulman targets the liberal press as much as anything else. Her homages to Barsotti, for instance, give her Instagram feed a mock-journalistic tone that is nothing but light-hearted. Which leads me to our recent obsession with online spoofs.

In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election, the topic of ‘fake news’ occupied the Western press almost on a daily basis, with a chorus of journalists and political commentators reprimanding the CEOs of major social media firms for having allowed misleading information to circulate on their platforms unchecked. The supposed neutrality of their algorithms was challenged by a number of international think tanks,19 with Google, Facebook and Reddit all accused of facilitating a ‘post-truth’ regime biased towards reactionary forms of propaganda.20 For some, the problem was that user-generated forums have come to be dominated by the language of invective, mockery and caricature. This had tangible consequences on the tone of the campaign, contributing to blur the distinction between reality, parody and straight up lies in the run up to the election. Writing for The New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum asked ‘How Jokes Won the Election: How Do You Fight an Enemy That’s Just Kidding?’ Online, Nussbaum wrote, ‘jokes were powerful accelerants for lies’, while ‘the distinction between a Nazi and someone pretending to be a Nazi for “lulz” had become a blur. Ads looked like news and so did propaganda and so did actual comedy, on both the right and the left – and every combination of the four was labelled “satire”’.21

In retrospect, it is possible to see how Privilege relates to this scenario. The performance parodies the fact that farce and travesty have become pervasive modes of expression. Ulman started out from the assumption that social media transform people into caricatures of themselves, but her performances show the opposite to be true as well – that is, that social media can turn a parody into a paradigm, a farce into a shared truth. This is partly because, online, information is not gauged qualitatively but quantitatively (how many times a message is shared, repeated, or re-tweeted), while any image can take on a life of its own as long as it is shared enough times. The more times a symbol is repeated, the more unhinged its meaning becomes. Ulman understood this early on. After all, ‘fake it until you make it’ was both the subject of her research and a personal mantra. When I talked to the artist, she told me that Pepe the Frog struck her as the most absurd example of this mechanism of symbolic displacement. Originally an amiable character from Matt Furie’s comic series Boy’s Club, in the late 2000s Pepe went viral on MySpace and 4Chan, and eventually on Tumblr too. Then, around the time of the US presidential election, the digital amphibian was appropriated by the Alt Right, and turned into a meme of right-wing atavism. A caricature of its original self, Pepe now wears a blonde wig and is a veritable totem for what its worshippers hail as the coming of ‘Trump-the-saviour’.22 The same people who glorify the new Pepe also believe that women are mere vessels for the reproduction of the species and that men are truly divided between Alphas (like Trump) and Betas or cuckolds, an emasculating insult reserved for the vast majority. This is the coded language of the most extreme fringes of the ‘manosphere’—a name for the network of forums, blogs and websites for those who share an obsession with reasserting positively medieval forms of patriarchy in the face of a feminist backlash of apocalyptic proportions (according to them). It takes less than an hour on the manosphere to rethink Ulman’s work as a brilliant antidote to misogynist trolling. Not only is she a woman who comes up with genuinely funny satires about the obnoxiousness of male desire, in Privilege she even plays Pierrot, the naïve husband who is permanently made a fool of by his cheating wife Colombina (meaning ‘little dove’ in Italian). Maybe Ulman’s version of the mask could be elevated to a nemesis of the Alt-Right’s cuck, though when I spoke to her she seemed more interested in comparing her pigeon friend to Pepe the Frog (fig. 9).

9. Amalia Ulman, Privilege, 2016, Instagram performance, digital still image, courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa.

Bob, Ulman explained to me, is something of a reverse mirror image of Pepe, in the sense that the frog went from friend to foe, while the bird encountered the opposite fate. When Ulman’s followers first spotted it flapping about inside Suite 1717, they felt compelled to send the artist all sorts of advice about how to get rid of it. But by the end of the performance, Bob had become their favourite character. How did the artist manage it? By giving Bob all the best lines. In this way, she deliberately made a pigeon—possibly the most detested embodiment of urban trash – appear just as lovable as a dove. Ulman told me with a chuckle that it was just too absurd. ‘Things cannot go on like this’, she said. Then she seemed to change her mind entirely. ‘You’ll see, this is just the beginning’, she added, without quite explaining whether she was referring to her work or to the political context we had just discussed in relation to the evolution of social media. I did not think to ask either, the distinction seemed beside the point.

1. Sarah Gram, ‘The Young-Girl and the Selfie,’ Textual Relations (2013), accessed 20 January 2017, http://text-relations.blogspot.ch/2013/03/the-young-girl-and-selfie.html.

2. Robert Smithson, ‘A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites’ [1968], in Unpublished Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), accessed April 20, 2017, https://www.robertsmithson.com/essays/provisional.htm.

3. Amalia Ulman, ‘Do You Follow? Art in Circulation #3,’ panel discussion, ICA, London, 17 October 2014.

4. Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (London: Verso, 1990), 50. Davis borrows this phrase from the German geographer Anton Wagner who, in 1935, compiled one of the earliest and most comprehensive studies of what he then described as ‘the Paris of the Far West’. See: Anton Wagner, Los Angeles…Zweimillionenstadt in Sudkalifornien [1935], cited in Davis, City of Quartz, 49.

5. Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyperreality (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986).

6. Amalia Ulman interviewed by Asher Penn for Lonely Girl (Martos Gallery, New York, 2013), accessed January 30, 2017, http://lonelygirl.info/amaliaulman.html.

7. That said, the fact that Ulman re-stages her memes of choice within a more complex narrative distances her Instagram art from the more cynical end of appropriation. A counterexample here would be Richard Prince’s New Portrait Collection (2014). Released shortly after Ulman brought Excellences and Perfections to a close, Prince’s series consists of over thirty ink-jet printed canvases that reproduce screen-grabs of his Instagram feed. In other words, Prince lifted other people’s posts and sold them as paintings worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

8. Molly Languir, ‘Amalia Ulman is the First Great Instagram Artist,’ Elle (October 2016), accessed December 22, 2016, http://www.elle.com/culture/art-design/a38857/amalia-ulman-instagram-artist/.

9. In 2013, the previously acclaimed actress Amanda Bynes was caught behaving manically on camera and on Twitter. A network of fans and conspiracy theorists speculated that it was a stunt (a piece of performance art in fact) that Bynes had orchestrated with the deliberate intent of boosting her popularity. This gave Amalia Ulman the idea for Excellences and Perfections. Bynes later revealed to have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. See Molly Lambert, ‘Career on Fire: The Increasingly Strange Case of Amanda Bynes,’ Grantland (2014), accessed January 15, 2016, http://grantland.com/hollywood-prospectus/career-on-fire-the-increasingly-strange-case-of-amanda-bynes/. I came across the term Trainwreck TV in David Ferguson, ‘What Makes Celebrity Meltdowns Entertainment Instead of Tragedy?’ The Guardian, 11 December (2016), accessed December 22, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/dec/11/what-makes-celebrity-meltdowns-entertainment-kanye-west.

10. Aria Dean, ‘Closing the Loop,’ The New Inquiry (2016), accessed 22 November 2016, http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/closing-the-loop/.

11. On Iggy Azelaia and her appropriation of black hip hop see Amy Zimmerman, ‘The Cultural Crimes of Iggy Azalea,’ The Daily Beast, 29 December (2014.), accessed January 21, 2017, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/12/29/the-cultural-crimes-of-iggy-azalea.html.

12. Amalia Ulman, in conversation with the author (December 2016).

13. Amalia Ulman, ‘Do You Follow? Art in Circulation #3,’ panel discussion, ICA, London, 17 October 2014.

14. Amalia Ulman in conversation with the author (December 2016).

15. Ibidem.

16. Ibidem.

17. Ibidem.

18. An example would be Allan Sekula’s documentary project Facing the Music: Documenting Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Redevelopment of Downtown Los Angeles (Los Angeles: East of Borneo, 2015).

19. See, for example: Kate Connolly et al., ‘Fake News: An Insidious Trend That’s Fast Becoming a Global Problem,’ The Guardian, 2 December 2016, accessed December 22, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/dec/02/fake-news-facebook-us-election-around-the-world, and Sapna Maheshwari, ‘How Fake News Goes Viral: A Case Study,’ The New York Times, 20 November 2016, accessed December 22, 2016 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/20/business/media/how-fake-news-spreads.html. For a much more thorough analysis of the way in which online news have loosened and corrupted previously held standards of truth and accountability, see Katharine Viner, ‘How Technology Disrupted the Truth,’ The Guardian, 12 July 2016, accessed December 22, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/jul/12/how-technology-disrupted-the-truth.

20. A recent investigation commissioned by The Observer concluded that Google’s search is biased towards right-wing predictions. See Olivia Solon and Sam Levin, ‘How Google Search Algorithm Spreads False Information with a Rightwing Bias,’ The Guardian, 16 December 2016, accessed December 22, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/dec/16/google-autocomplete-rightwing-bias-algorithm-political-propaganda.

21. Emily Naussbaum, ‘How Jokes Won the Election: How Do You Fight an Enemy Who’s Just Kidding?’ The New Yorker, 23 January 2017, accessed January 23, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/23/how-jokes-won-the-election.

22. On Pepe the Frog and the rise of pseudo-religious symbolism on Alt-Right sites, see Tara Isabella Burton, ‘Apocalypse Whatever: The Making of a Racist, Sexist Religion of Nihilism on 4Chan,’ Reallife, 13 December 2016, accessed December 22, 2016, http://reallifemag.com/apocalypse-whatever/.