The Sickness of Being Disallowed: Premonition and Insight in the ‘Artist’s Sketchbook’

Sheila Gaffney

To cite this contribution:

Gaffney, Sheila. ‘The Sickness of Being Disallowed: Premonition and Insight in the ‘‘Artist’s Sketchbook’‘.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/sickness-disallowed-premonition-insight-artists-sketchbook/.

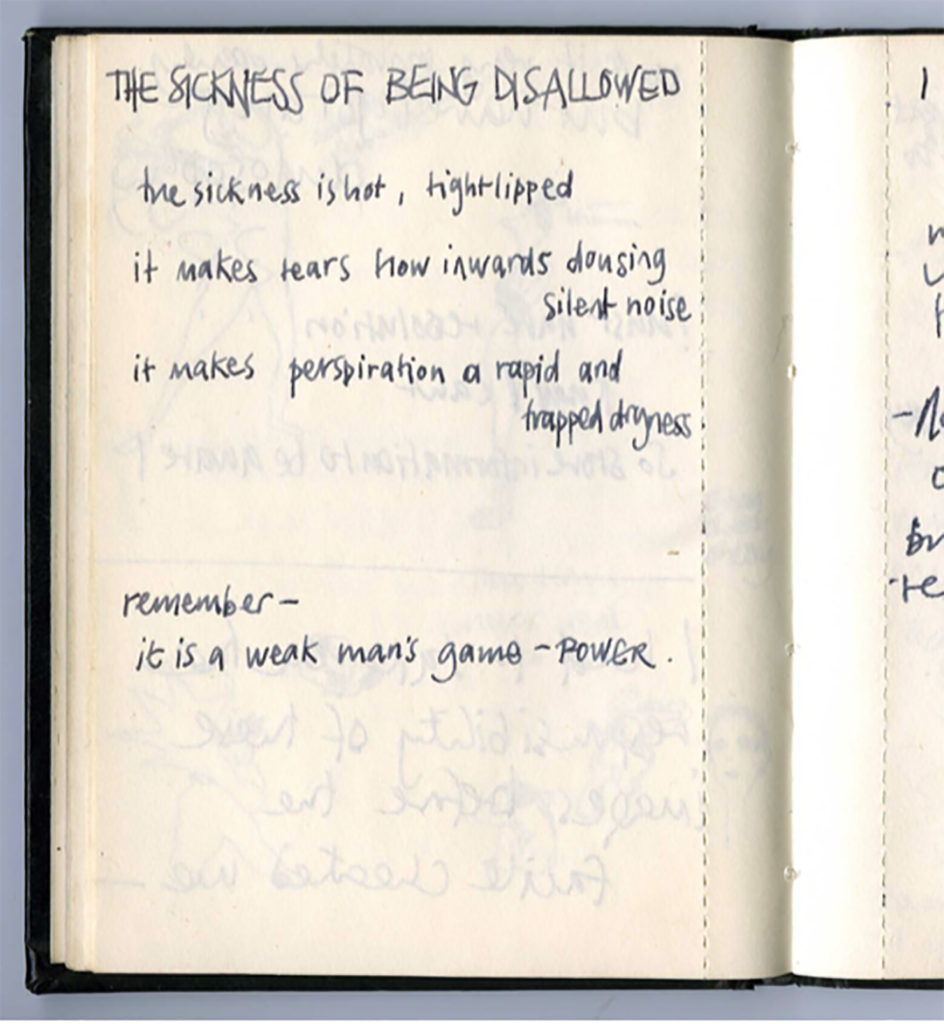

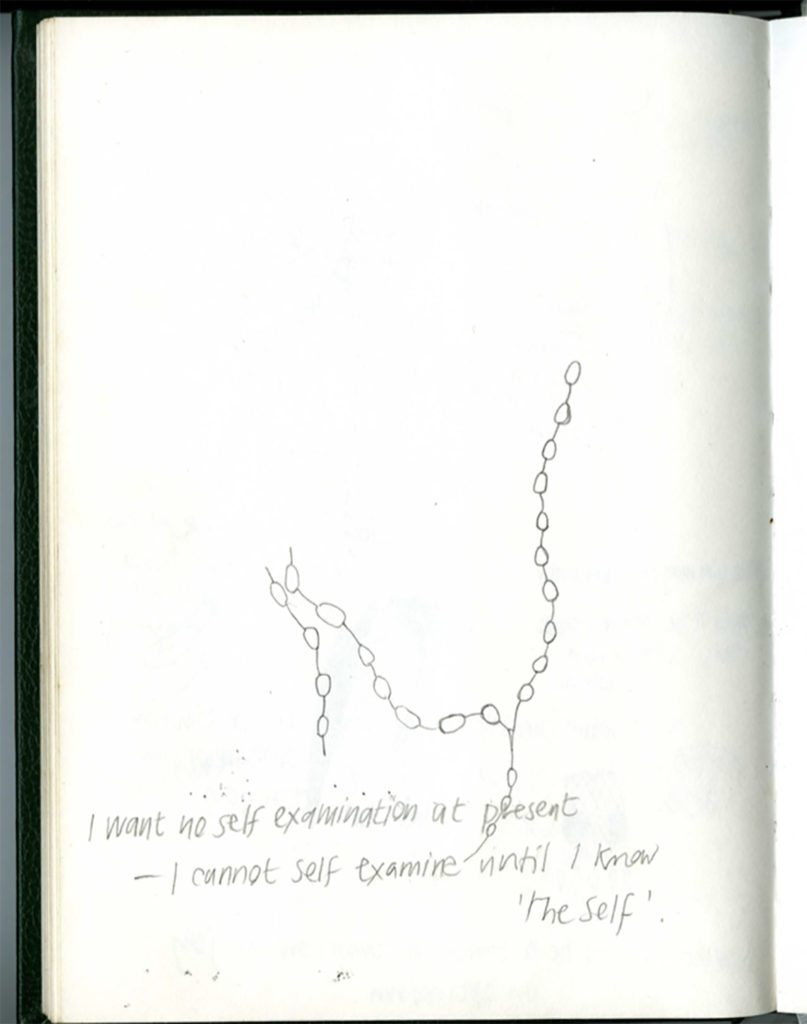

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1983, ink on paper, 10cm x 15cm.

How can insights from 1983 count as part of the research process for work made and exhibited much later? The sickness of being disallowed offers an example – a page constituting an emotional register made in 1983, saved at that time as an attempt to hold on to a feeling. I would now, in 2017, argue that it evidences a very important knowing in the moment, which is an essential part of the sculpture I make as a more experienced artist today.

Then

I remember a day in 1979. It was the end of my first year studying sculpture, and I had been away for the weekend. I had no anxieties about the world at large, only about art and wanting to make art, and had hitchhiked with a friend from London to Herne Bay and back. On the return journey, two backpacked, partied-out young women were tipped out of a long car ride into the noisy, dirty, post Sunday morning market space formed by the junction of Commercial Street, Commercial Road, Whitechapel Road, and Lehman Street in East London. This area is described by a current travel guide as ‘full of noise, colour and life…a palimpsest of culture’.1 However, then, on a Sunday afternoon, this location was hot, dry, tired, worn, closed down and unpeopled. We stood on roads and pavements littered in post carnival condition and somatised the vehicular noise. Food packaging, plastic, random abandoned fruit, vegetables and used clothing formed a native tumbleweed. We needed to find fresh and flushing water to restore our bodies, and eventually spotted one discreet but open public doorway, that of the Whitechapel Art Gallery. This immediately became our oasis and curiously (although I didn’t know it then) it addressed my nascent wonder about sculpture and my ambition to be a sculptor.

So I first set eyes on the sculpture and drawings of Eva Hesse, an American artist whose work I had never come across, as I stumbled in from an inner city road intersection to use a public convenience.2 At that time, Hesse’s works were not the ageing, petrified conserved pieces that arrived in the Tate in 2002.3 They were the fresh, fragile, hypnotic, disruptive, audience-grabbing presences we can now only know partially through iconic photographs.4 They were delicate, lightweight, twinkly, tactile, hard, soft, fleshy, shiny, and sometimes see-through. They did not follow the line of logic of British sculpture that I was learning at college, with its heavy lexicon of object, gravity, space, carved, constructed or modelled.5 The works on show possessed, within their material forms, an embodiment of emotion, and were free from the visual interference of interpretive panels. I was with the works in a space in which viewers moved slowly, stopping when and if, to simply gaze and take in each phenomenal form. Every piece of work was redolent of bodily presence, and I immediately sensed that this exhibition experience was special. It has continued to have a great impact on me.

The exhibition occurred after Hesse’s death, yet the artist’s voice was present – not only emerging from the materiality of the works, but also in the accompanying publication. The forward to the catalogue, written by Nicholas Serota, states ‘it is through sculpture that a rare and fine sensibility continues to communicate with us’.6 This claim, although true in many instances, slightly misrepresents what sensibility means in the case of this artist. The statement privileges the sculptural object, and separates it from the woman creating it.7

Fourteen of the fifty-six pages that formed the publication were filled with selections from the artist’s personal diaries and notebooks revealing her writings on work and ideas about art. The reproduced pages were designed to replicate the authentic layout, spelling and punctuation of the originals. Sensing her voice through reading the catalogue, statements written by Hesse such as ‘It just seems to me that the “personal” in art if really trusted is the most valued quality and what I want to find so much in and for myself’, followed by the underlined cry ‘only knowledge of the self is possible’ resonated within my moment of aesthetic encounter, and framed this happenstance.8 I still remember viewing the tangle of latex rope and wire which makes up Untitled 1969–70 and the priapic group of standing fiberglass and polythene forms that constitute Untitled 1970.

It was a body-to-body engagement. Both works hung before me and around me on transparent strings, defying any truth to materials held dear in the UK condition of sculpture.9 Hesse’s work introduced a paradoxical challenge where her non-truth to materials presented a new idea, a truth to emotional honesty.

Eva Hesse wrote:

In my inner soul art and life are inseparable…[I] am interested in solving an unknown factor of art and an unknown factor of life…in fact my idea now is to counteract everything I’ve ever learned or been taught about those things – to find something that is inevitable that is my life, my feeling, my thoughts.10

To me these words signal issues of gender, aspiration, seriousness, vulnerability and, continuing Hesse’s own style of expression using ‘opposites’,11 certainty about all that was uncertain. I propose that in this encounter there is a synergy of exhibition and archive of antagonism, where the archive is Hesse’s written papers expressing her contention with the depersonalization of art in the examples she knew. This is an exemplar of the seamlessness between material making and psychic life.

Personally written accounts of creative practice often include time-based approaches that appear diaristic. Marion Milner’s early work, A Life of One’s Own (1934) published under her pseudonym Joanna Field, is an analysis of her own moments of everyday life, a genuine experiment to record feelings and her actions to explore her own psyche.12 This work was the precursor to her ruminations on painting in which she used the creative act of that medium to research and deepen her understanding of psychoanalysis.13 Anne Truitt’s Daybook: The Journal of an Artist (1982) recounts her contemplations ‘reconciling the call of creative work with the demands of daily life’.14 Truitt’s account is different in tone from Milner’s, employing a more gentle, considered reportage, recording her domestic responsibilities alongside the production of minimal art. Truitt embeds questions about her artistic self within a narrative of recognizable life routines, and her prose interrupts the biographical myths of the male artist.15 Both of these authors reflect extensively on, yet their writing partly removes them from, the artistic process in play. Hesse’s writing, in the form which I engaged with it in 1979, exhibited a more urgent voice. The sentences, paragraphs, phrases and lists do not flow together as a carefully crafted single narrative. They read rather as a collection of exclamations, and therefore, crucially, gave me permission to generate my own utterances in a written form. To this day when I am making sculpture in my studio I always have a book in which I am saving what I would perhaps call ‘scraps’ of my unconscious.

Now

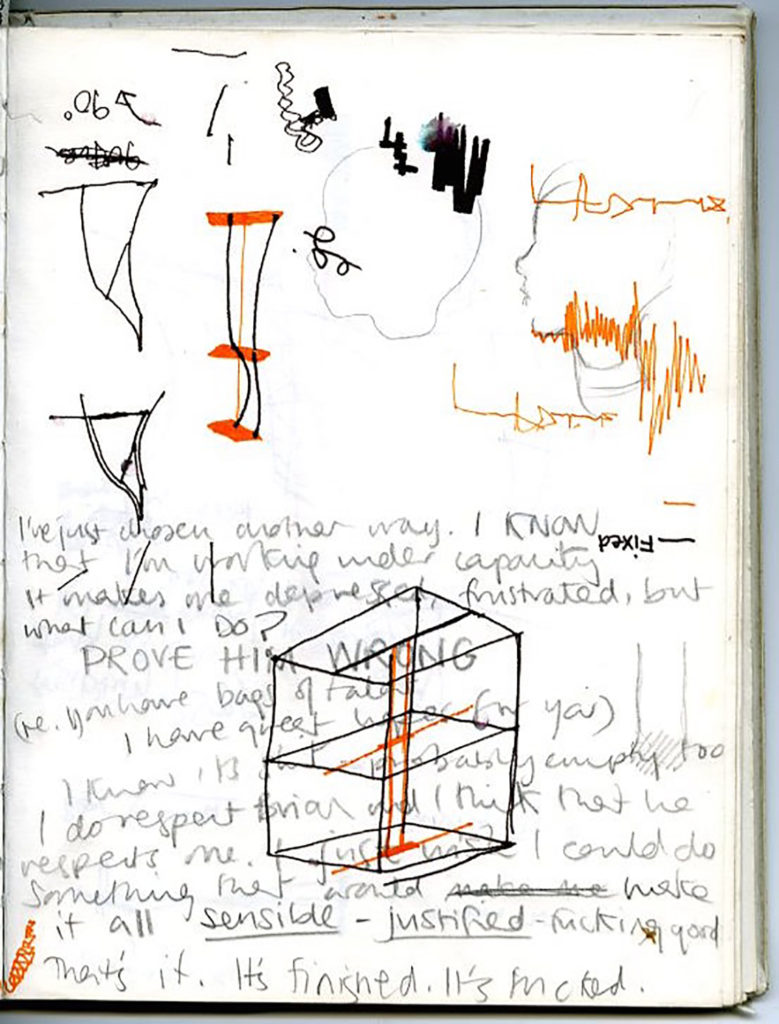

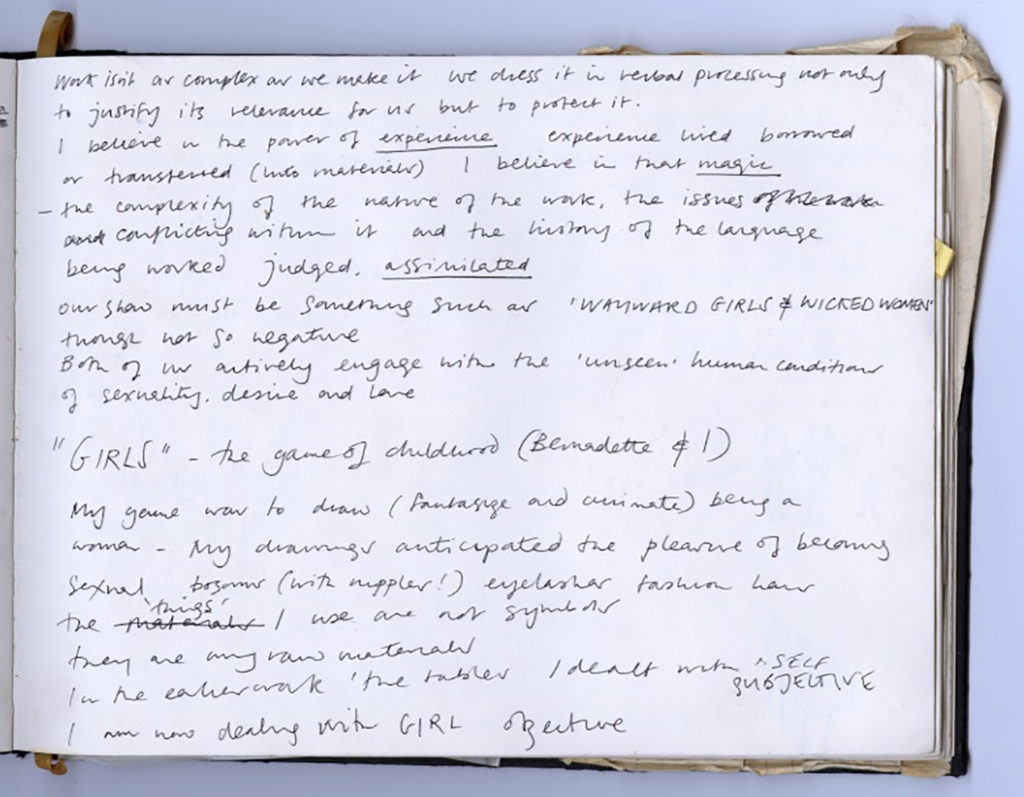

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1980, pencil, felt tip on paper, 18.5cm x 34cm.

I think of these scrap entries as ‘emotional registers’ or ‘feelings’, and they have become part of my art practice, although not when my work is exhibited. From the moment of encounter with Hesse at the Whitechapel, and afterwards in my acts of writing-out-alongside-making, I have felt it is acceptable to gesture, and to converse with myself, with the art I am making and with the art of the wider world. Citing these utterances as relevant in my practice might appear illogical as they were not initially generated to be any deliberate part of my process, but in this contribution to OAR I am proposing that, in fact, they are crucial to art making. To put this in other terms, after Hesse’s writings had signalled to me that psychic life played an important part of an artistic practice, I understood that in my practice the way thoughts ran through my mind could be as important as my hands and eyes when making sculpture.The pages I present in this contribution are taken from one of what could be recognised as my artist’s sketchbooks, compiled as part of my sculptural practice. There are numerous models of seamless relationships between artists and their sketchbooks. J.M.W. Turner’s sketchbooks are still available in monograph form claiming to be reproduced ‘as close to…actual size as possible…in four-color offset lithography, so that they are extraordinarily faithful to the original work’.16 Pablo Picasso’s sketchbooks toured six countries in an exhibition titled Je suis le cahier: the Sketchbooks of Picasso which presented ‘the legacy by which we may decipher the process of Picasso’s creativity and understand the cohesive totality of his lifework’. As viewers of it we are told ‘the sequence of drawings within a given notebook is important to an understanding of the creative process’.17 However, these should be seen for their contemporary relevance, and not a necessary template for future cultures. Current examples include the collection Donald Rodney’s Sketchbooks (1983–90), in which the artist ‘made a conscious decision to treat his sketchbooks as ongoing works of art’, and the notebooks of Helen Chadwick, which survey her everyday social world, as well as show her idea development, plans, diagrams and measurements for her many well known works.18

My own books do not fit into these models and have properties more in common with ‘commonplace books’, compilations which became popular in early modern Europe between the late 15th–18th Centuries. Commonplace books are:

A way to compile knowledge usually by writing information into books. Such books are essentially scrapbooks filled with items of every kind: recipes, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, proverbs, prayers, legal formulas.19

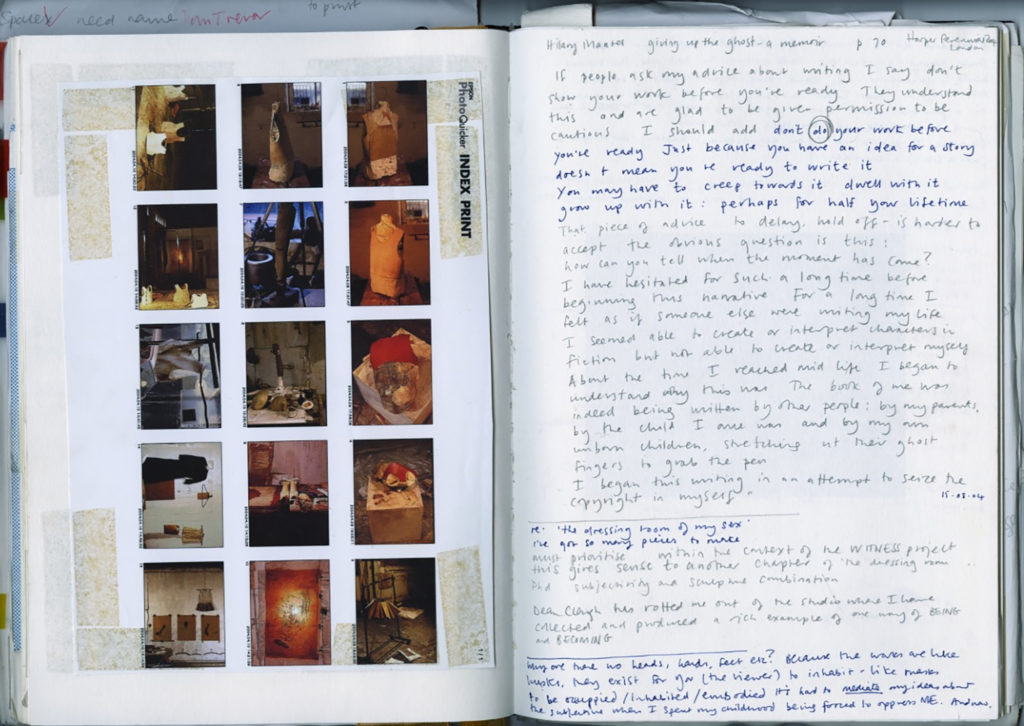

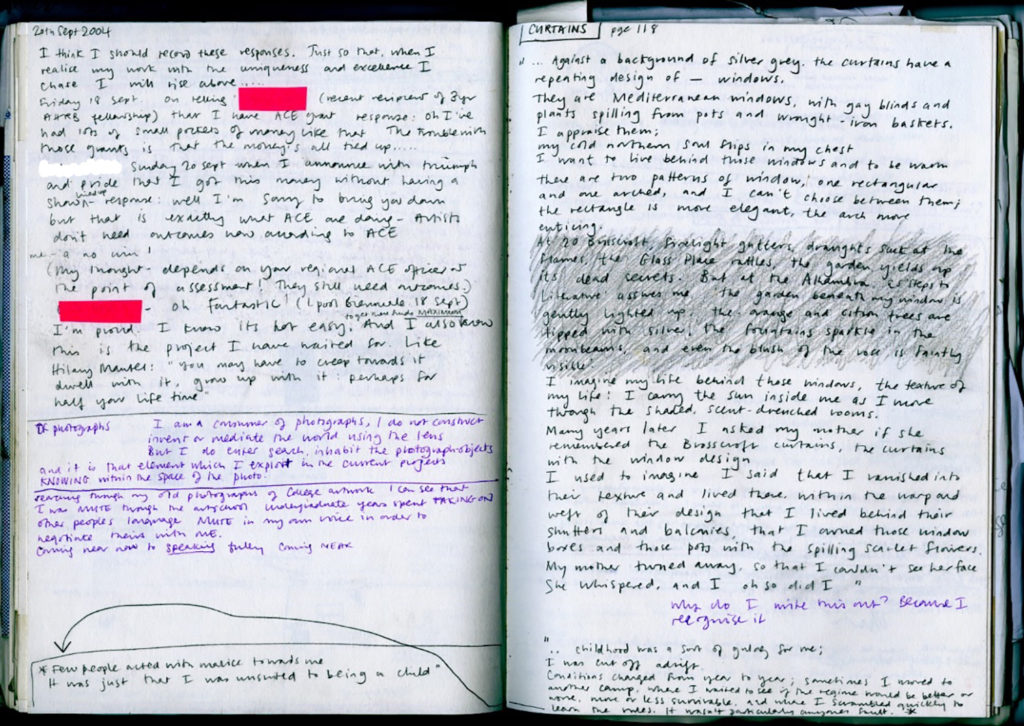

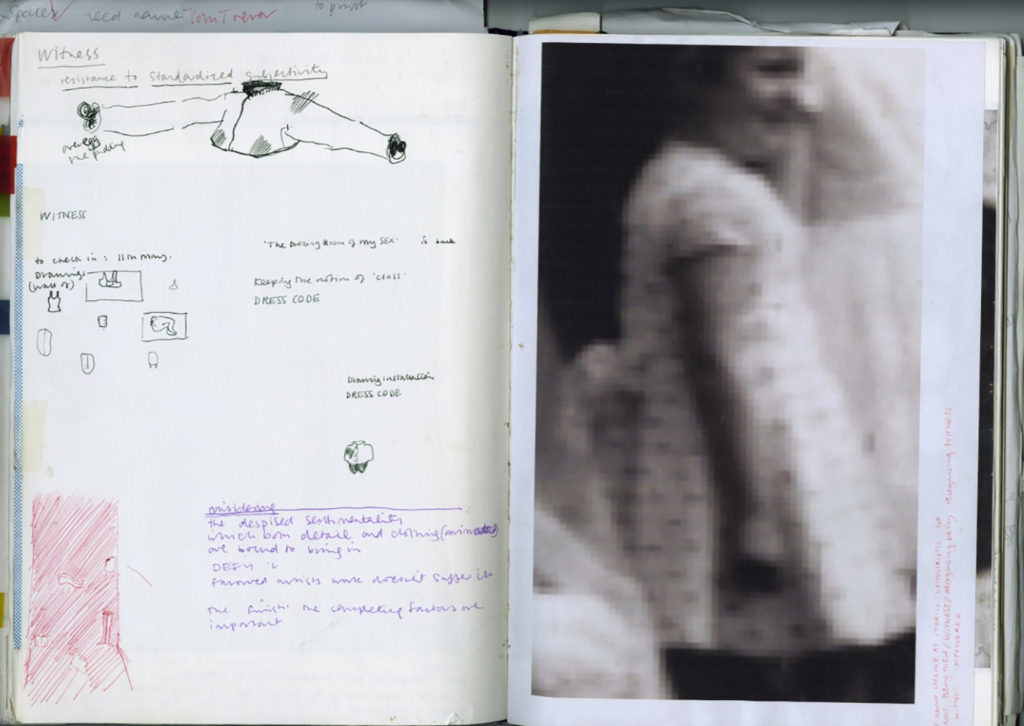

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook double page saving words from Giving Up The Ghost by Hilary Mantel (2003), 2004, ink, digital print on paper, 42cm x 29cm.

Newton’s Papers contain examples of commonplace books,20 and in Elena Ferrante’s recent Neapolitan Novels readers followed the ‘very ordinary, dirty notebooks’ of the central character Lila. The author names them to be zibaldone, Italian vernacular commonplace books dating from the fourteenth century.21 In a similar way, I think of my books as a non-professionalized, unfettered repository, formed as a self-reflexive rehearsal space for becoming a woman artist, an identity I have maintained since 1977. However, I am not the first to adopt this way of working. The early notebooks of the artist, choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer have been cited as an example of the way in which ‘sketchbooks operate as performative manifestations towards becoming an artistic self’.22

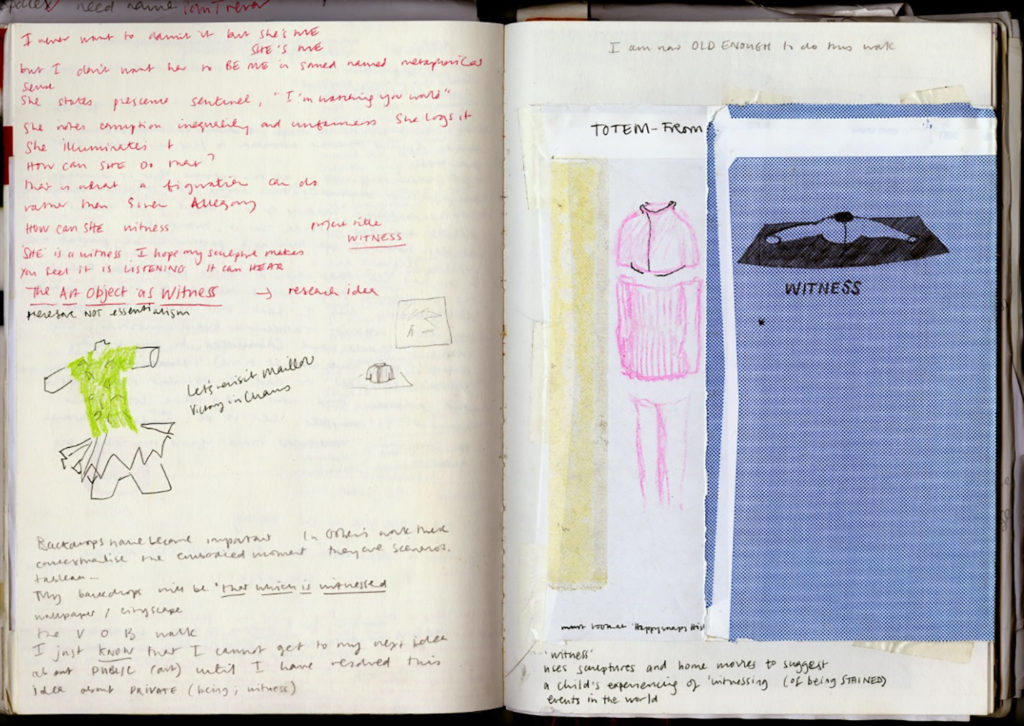

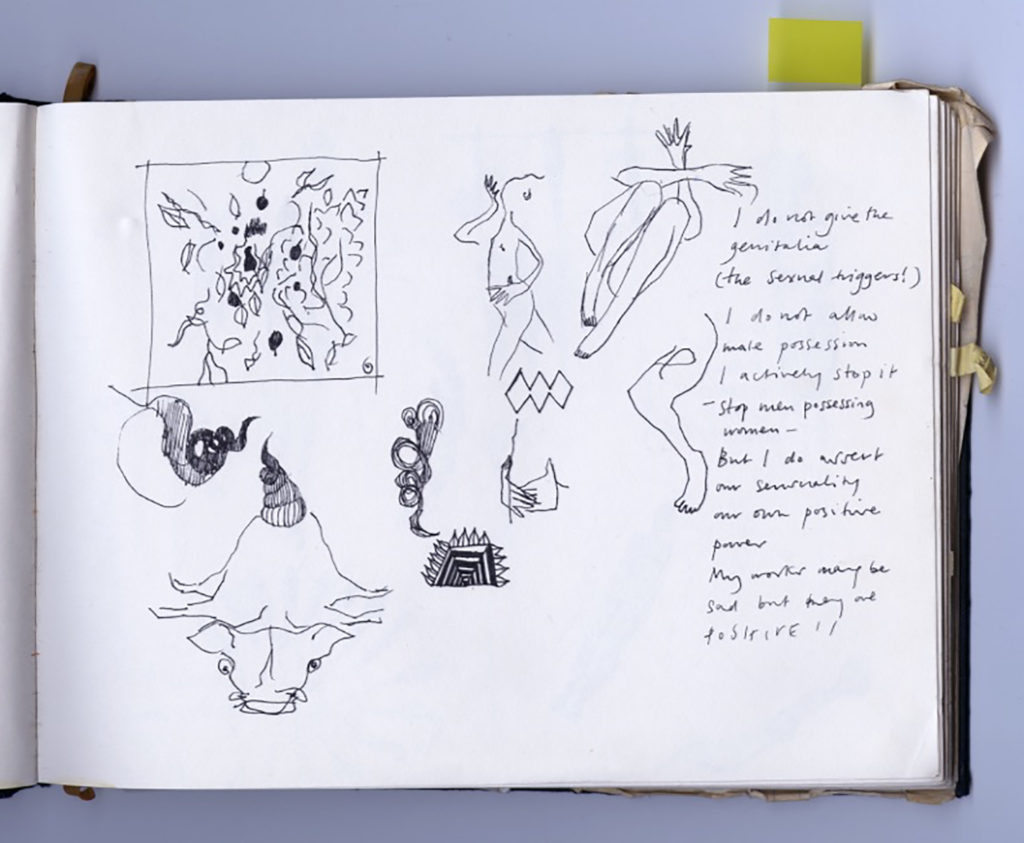

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook double page, 2004, ink biro, crayon on paper, 42cm x 29cm.

Typically, as in the first sketchbook page pictured above, entries sit on pages simply stored and waiting to be employed in future work: a swatch of colour, a brushstroke or a cartoon. The pages are packed within the leaves of books, which hold fragments of material textures, thumbnail sketches, visual representations of sculpture I may never make, many to do lists, and, most significantly for my contribution to this issue, written personal insights. As with commonplace books these were never made for public inspection or publication. I have consolidated them as an outcome of the process of learning to become a sculptor. They now form a record made within the 1980s feminist framework, a framework that emphasized the concept of woman as ‘other’.23

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook double page saving words from Giving Up The Ghost by Hilary Mantel (2003), 2004, ink, graphite on paper, 42cm x 29cm.

My personal, feminist, project of social and cultural emancipation can be traced back precisely to my sketchbook-based repository. Confronted with research conditions set by university culture, which Patti Lather characterises as ‘a dinosaur culture of master narratives’, I want to challenge the temporal limitations set by institutional culture in the UK, and their insistence on objective and measurable criteria, and claim the subjective registers as constitutive of validity in my own artistic research.24 With this attitude, how can the way of working I describe and undertake in my studio be recognized as part of today’s ‘systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources to establish facts, reaching new conclusions’?25 How can this way of working (and these pages) evidence what would now be called artistic research? Can I qualify these subjective registers, across time, just described, to measure the progress of learning to be an artist? This is the scene of my own antagonism towards the difference I observe between the reception of artists’ insights in the public realm and the conditions set to justify such in academia.26 This is carried forward from my encounter with Hesse to the present day, and it is resonant with the words of the feminist educationalist Penny Jane Burke who states:

Knowledge that is legitimized by universities is often constructed as large scale, attached to quantitative methods, objective and value free. It is often characterized as detached from the personal and political, although feminist theorists have argued that ‘Knowledge is always situated and tied to wider power relations that are classed, gendered and racialized’.27

Therefore I look to Lather’s aspiration ‘toward opening up our privileged spaces in the production of a politics of difference that recognizes paradox, complicity and complexity’.28 I believe her work to free validity from being a fixed dominant ‘limit question’ is useful to artistic practice, including mine, in which the subject engages reflexively in a search for meaning constructed both by others and her selves.29

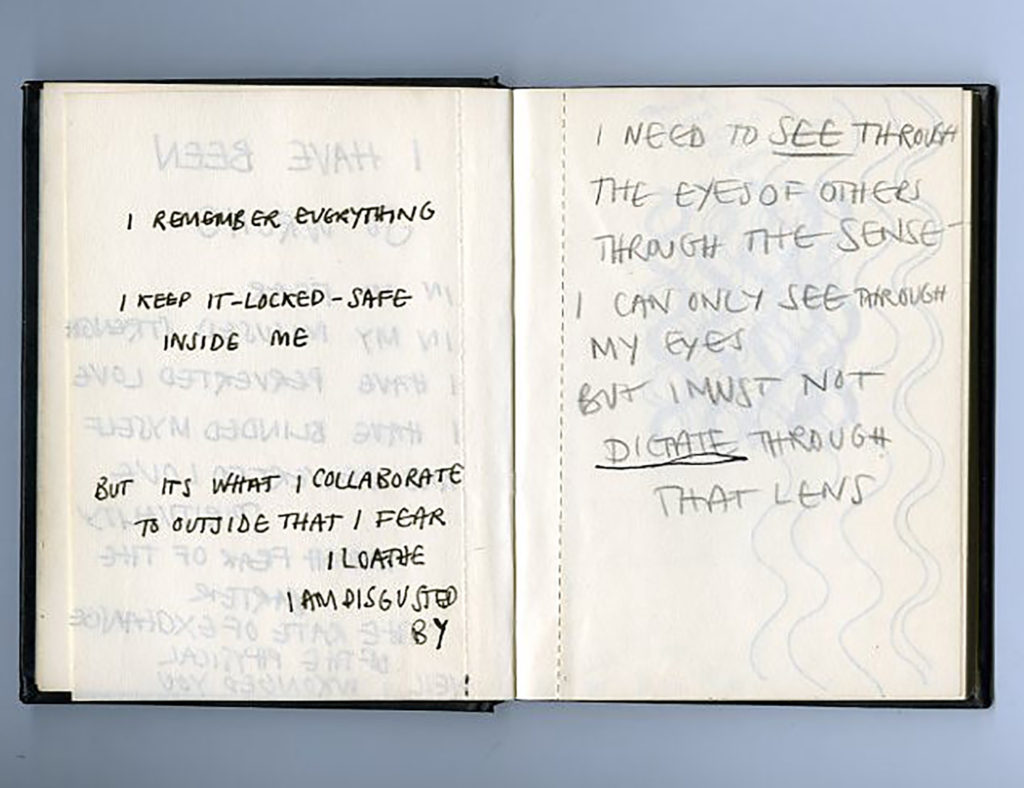

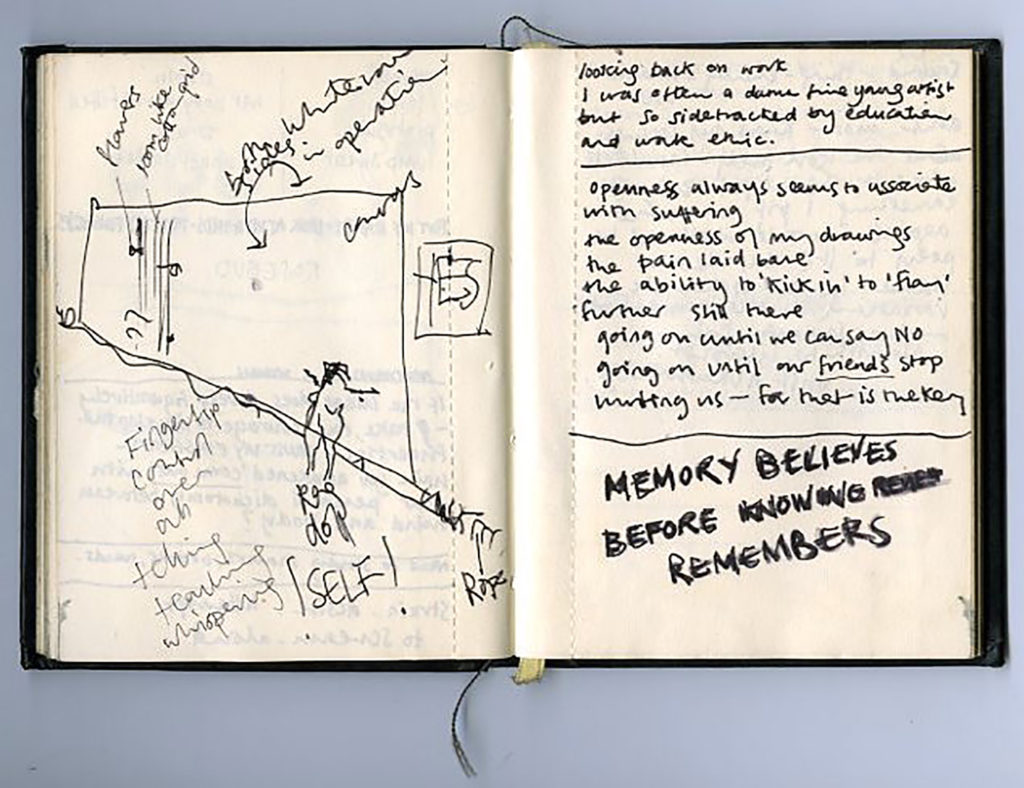

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook double page, 1982–84, ink, pencil on paper, 15cm x 20cm.

Lather believes ‘strongly that in our action is our knowing’.30 I came of age artistically within a culture now historicized as ‘British sculpture’ in which there was a collective desire to redefine what sculpture was and could be in the late twentieth century.31 In essence being part of this encouraged sculptors to create their own criteria for success. If, as Lather says, ‘our invested positionality shapes our rhetoric and practice’,32 then it is crucial to explore ways in which these registers are still active and have value now as I work as a sculptor, acknowledging their formation within British sculpture and its post practices,33 where the question of gendered subjectivity is not a condition.

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1991, ink on paper, 25cm x 9cm.

On reflection when looking at the pages of my books, I now see that my saved emotional registers are of two different types.

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1991, ink on paper, 25cm x 9cm.

The first type of emotional register can be thought of as a collection of scaffold pieces, piled up to help me reach a sort of respectability. Respectability is ‘usually the concern of those who are not seen to have it’, as the sociologist Beverley Skeggs concludes.34 Skeggs’ research is about attaining respectability in terms of the norms of social class. My own frame of respectability is the canon of British sculpture. The saved scaffolds assemble and I hoard them to help me make strategy to intervene in territories, find form for expressing anger, assert my demand for recognition and the acceptance of a different voice within this canon.

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1984, pencil on paper, 15.5cm x 21.5cm.

The second type of emotional register is that which I call ‘knowing in the moment’, and records premonition, insight, emotion and feeling. This knowing in the moment to which I refer is a fleetingly glimpsed mental image or thought that I would like to express through sculpture, but can neither configure nor facilitate at the time. This differs from other formulations on knowing in art, such as Rebecca Fortnum’s recent propositions.35 Fortnum acknowledges ‘not knowing’ as a much used term by artists and she researches ‘from primary sources, using the words of artists to examine moments in an art practice when artists negotiate their own knowledge’.36 She focuses upon descriptions of artists’ processes to create and contrive states of ‘not knowing’. My interest in her idea is related to the history of art school teaching in Britain. Models such as ‘Basic Design’ are still used as contemporary reference points in studio practice teaching, predominantly at elementary diagnostic stages.37 Fortnum finds commonality amongst artists who ‘want to encounter, in their final work, something that does not feel known to them’ and presents this as an outcome each has sought through a strategy.38 Such strategies may involve changing medium in order to suspend conscious deliberations, or ways to displace the artist from the centre of events. Such an argument relies on a ‘Eureka moment’ that reinforces the idea of finding knowledge as the result of process.39 My state of knowing in the moment is only legible as part of process by viewing it retrospectively. When I first write down a scrap (an emotional register), it has more to do with what I am certain of at that time, and should be thought of as a form of knowing before-I-can-do, or thinking-in-front-of-making. I only begin to claim relevance for these entries now, in 2017 (or in future moments), after a long personal practice of searching through the books to retrieve remembered items whilst engaging in making sculpture. Therefore, the material to which I am referring can be thought of using the term ‘pre-process’.40

Psychoanalytic concepts have allowed feminists to rethink the art practices which we, even now, are continually working to reshape, and are an integral part of my personal ‘perspective’.41 In order to express in this way, I am drawing on the idea of artistic research as ‘a context-aware and historical process that works ‘inside-in’, beginning and ending with acts committed within an artistic practice’.42 Central to this ideal for artistic research, done inside practice, is the issue of the researcher’s perspective which can be put simply as ‘who is the one doing things’, to acknowledge that this stance ‘alternates and changes positioning of articulation within the given practice’.43 As a feminist, I now overtly claim the self as the subject of the sculpture I make, an approach I struggled to make have universal interest as a young sculptor. This self as subject is not some sort of uncontrollable oozing of expression through art materials. In my current ‘photoworks’, I employ a strategy to ensure this does not occur, and begin making the sculpture using analytical drawing and measuring methods to interrogate a family photograph of myself as a child. The photograph provides me with a register of classed and gendered subjectivity, situation, place and an internalized knowledge, which I source as I use the data extracted from the image, to model in wax and distill the form of the child I remember being in that moment of time. This is how, bringing forward an analysis of myself within the sculpture, I use my own agency and lived experience alongside and within my material manipulations.

Family photograph, Phoenix Park, 30th August 1966, 9cm x 11.5cm (Sheila Gaffney second from left).

Sheila Gaffney, These at least were things she could remember, 2015, bronze, 3cm x 3cm x 12cm.

Alongside this, I life-write through my process of making to give insight to my own form of what I propose is an ‘inside-in’ methodology.44 When writing through my work, I attempt to both articulate and extrapolate my ‘thought position’ in sculpture.45 To do this, I have looked to Object Relations Theory as developed by Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott.46 I suggest this framework helps us to understand how to model the internalized and mental complexity of the maker in the moment of making that had no place in the teaching of sculpture, from which I learnt as a young student.

The framework of Object Relations Theory ‘places the human being in a dual world of external and internal relationship’, where the inner world of the person is ‘a changing dynamic process’.47 Christopher Bollas expands this strand of ‘the illusion that is psychoanalysis’ by proposing the idea of the transformational object, which defines the psychoanalytical idea of the early experience of the Mother not as an object but as a process: one that continues into adult life, altering self experience.48 When I first read this book, which is a theory of psychoanalysis, I experienced it as a description of my own knowledge of creative making and the culture in which I learned. I saw a parallel between my experience of becoming a sculptor and Bollas’ descriptions of how we move from wordless transformational experiences to finding language to articulate experience. The usefulness for the creative artist lies within the written depiction of the inner relationships and processes we call the psyche. Bollas’ ideas can be applied directly to the emotional registers on the pages of my sketchbooks. Bollas writes ‘It is an ordinary feature of our mental life to engage in sub-vocal conversations with oneself’, telling us that ‘much of psychoanalysis is about the nature of intrasubjective relations to the self as object’, and ‘this constant objectification of the self for purposes of thinking is commonplace’.49 I recognise my ‘scrap’ habits in these descriptions, and liken my emotional register to an ‘intrasubjective utterance’. Furthermore, the concept of ‘the unthought known’ as an idea, ‘to stand for that which is known but has not yet been thought, if by thought it is understood that we mean that which has been mentally processed accurately’ is helpful to further understand the pre-process relationship of the emotional registers to the sculpture I make now.50 Bollas describes his own notebook culture as an act where:

I enter the idea in my notebook without straining to push myself beyond what I know exactly at that moment…[A]lthough I am working on an idea without knowing exactly what I think, I am engaged in thinking an idea struggling to have me think it.51

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1992, ink on paper, 25cm x 9cm.

In this context my journal pages evidence my lived experience as ‘unthought knowns’ captured on the page. My own utterances, and the words of the writers I have read and saved, articulate together something like Bollas’ unthought known. I believe my own words and images in the pages of the books are the result of an impulsive grab to capture such in scripto-visual form, and when sourced or used become that which is known. With every touch of the wax surfaces I form in the modelling process to create my sculpture, I am processing these registers both mentally and somatically to become thought.

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page, 1992, ink on paper, 25cm x 9cm.

Through the ideas of Christopher Bollas, I have found a way to articulate the relationship between the sculptural work I exhibit in the public realm and the pre-process emotional registers generated in my commonplacing. Currently, I use the idea of the intrasubjective utterance to map through and within the culture that was teaching sculpture in Britain in the late twentieth century, and demonstrate the psychic frame at play as an integral element of the sculptural imaginary.52

Drawing on these theorists is itself an attempt to qualify my post-Hesse practice in sculpture, as well as a way to raise questions about the human relationship with making and thinking through psychoanalytical terms as a process. In effect, I’m proposing my archive of commonplace books contributes to a paradigm-after-Bollas, and as such it mirrors the problematic at the core of Lather’s demand for ‘a site that “gives to be seen” the unthought in our thought’.53 I am conscious that I am coupling the Foucauldian thinking of Lather with psychoanalytical thought of Bollas, which in an academic context may seem incongruous. It is not uncommon for artists to bring seemingly incompatible ideas together in the material practice of making, and therefore the ‘inside-in’ artistic researcher may not perform a straightforward logic in what they call their process.54

The ‘scandalous categories’ of validity that Lather proposes are essential for allowing such a feminist project to move further into speakability.55 The emotional registers I have saved in sketchbook mode are now an addition to the artistic vocabulary, ready to be articulated. Furthermore, they can be treated as information in this watchful, reflective, self-aware generating of knowledge which is a crucial part of my identity as a sculptor. As Lather says ‘There is much in my performance as a researcher I cannot reach, much that eludes the logic of the self-present subject’.56

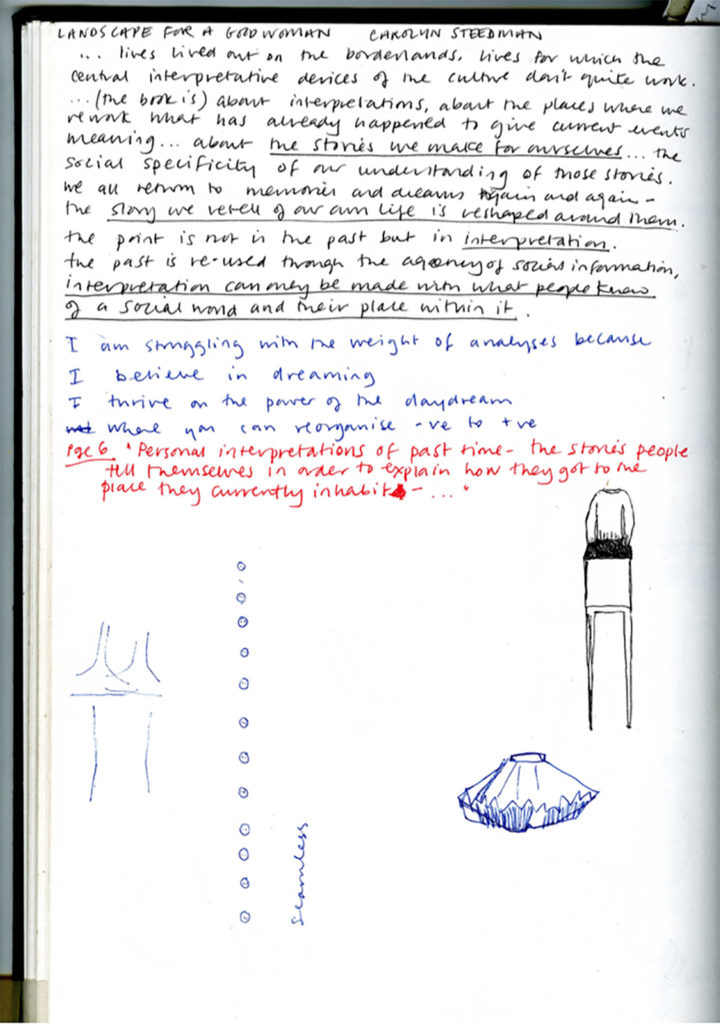

Sheila Gaffney, sketchbook page saving words from As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930), 1982–84, ink on paper, 15cm x 20cm.

In my ‘inside-in’ research project, which draws upon and sources inner states of mind, I am anticipating a problem to demonstrate some criteria for validity other than self reflection and comparisons with relevant and significant examples found in other artists’ work. Using Lather’s imagined checklist for Ironic Validity, my emotional registers foreground what she calls the insufficiencies of language. The emotional registers resist, due to their relation with a moment in time (Lather’s) ‘the hold of the real’, and gesture ‘towards the problematics of representation’. The accumulated book contents are now ‘the generation of research practices that take the crisis of representation into account’.57 Encouraged by Lather’s work, I propose the psychoanalytical framework outlined to position these scraps as part of what we call thinking and being. What I am doing in this is creating an objective relationship between myself as maker, inquirer, and subject ‘to make the familiar strange and see things through critical eyes’.58

Lather’s Ironic Validity is a gift to the problem for creative work such as mine in an institutionalized research project, but the work itself is also a gift to Ironic Validity. My journal entries perform similar theoretical moves if they were made, for example, into a research training video, resembling Pixar’s recent animated feature Inside Out (2015), inspired by Robert Plutchik’s Psychoevolutionary Theory of Basic Emotions.59 In my imagined video the characters on the pages could model and perform the ironic parts of Lather’s transgressive checklist, acting out the insufficiencies of language, the production of meaning effects, producing truth as a problem and resisting the hold of the real.

Lather’s own ‘seeming obsession with the topic of validity’ from her position as a feminist offers a space in which I can valorize these essential scraps of me.60 I would like to see the feminist project in which I have participated and shared here become a normative model for the future of art as research, and receive recognition as such. Certainly, my sketchbooks contain premonitions rather than knowledge, and these insights pre-empt a future stage in the process of making, rather than perform a past knowledge that is already known by others. In my current, ‘mature’ practice I work with Lather’s welcome intervention for the feminist into artistic research. Her aim of ‘developing inquiry-approaches…that move us toward ways of knowing which interrupt relations of dominance and subordination’ enables the inclusion of emotional registers in my research practice.61

Many years later, all the registers of Hesse, such as written utterances, drawings and sculpture, are now recognised as one opus. Feelings are now facts in any ongoing examinations of Hesse.62 However, it is still difficult for feminist artistic researchers to present an art practice in its entirety, which may include private and personal disclosure,63 when making original contributions to knowledge.64 Artistic researchers require opportunities in which to claim voice-positions while they are alive, and not wait for posthumous archival discovery. New tools are needed to do this. Lather’s work offers a necessary and appropriate apparatus, which will work within an ‘inside-in’ methodology, to meet the contemporary lust for scrutiny, audit and legitimization which can be read off current institutional conditions in the UK higher educational sector. In addition, her work offers a release from what I once, a long time ago, imagined myself to be suffering from – the sickness of being disallowed.

1. ‘Brick lane,’ in Lonely Planet, accessed 21 May, 2017 at https://www.lonelyplanet.com/england/london/attractions/brick-lane/a/ poi-sig/372035/358914.

2. Eva Hesse: Sculpture, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 4 May–17 June 1979.

3. Eva Hesse, Tate Modern, 13 November 2002–9 March 2003.

4. The deterioration of Hesse’s work due to her use of experimental materials is well documented. The iconic photographs to which I refer originate in her New York studio and exhibitions. See: Lucy Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York: New York University Press, 1976).

5. See: William Tucker, The Language of Sculpture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974), and William Tucker, The Condition of Sculpture: A Selection of Recent Sculpture by Younger British and Foreign Artists (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1975). Phyllida Barlow writes of learning UK sculpture in Mark Godfrey and Jon Wood, Objects for…and Other Things: Phyllida Barlow (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2004).

6. Nicholas Serota, ed., Eva Hesse: Sculpture; 1936–1970 (London: Trustees of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1979), 3.

7. However, Anne Wagner states her mistrust of how such writings may have had a reductive and detrimental effect on the way in which Hesse’s work can be understood within the history of art. Anne M. Wagner, ‘Another Hesse,’ in Eva Hesse, ed. Mignon Nixon (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 97, and Griselda Pollock and Vanessa Corby, Encountering Eva Hesse (Munich: Prestel, 2006).

8. Serota, Eva Hesse, 12, 18.

9. Truth to materials is a phrase describing a school of thought which believes the innate quality of the material used is a determining value in the making of the sculpture, so that ‘the artist must be true to his materials: [s]he must respect intrinsic qualities of the medium so that the viewer will be aware of the appropriateness of the image to the substance that has given it form’. Albert E. Elsen, Origins of Modern Sculpture: Pioneers and Premises (Oxford: Phaidon, 1974), 120. Elsen attributes this influence in sculpture in Europe and USA to Aristide Maillol, Constantin Brancusi, and Jacob Epstein. This value in British Sculpture is often attributed to Henry Moore, and has remained a discussed tenet in the art school teaching I experienced. See also Phyllida Barlow’s recollections in Phyllida Barlow, ‘Heresay, Rumours, Bed-sit Dreamers and Art Begins Today,’ in Godfrey and Wood, Objects for…, 211).

10. Serota, Eva Hesse, 23.

11. Ibidem.

12. Joanna Field, A Life Of One’s Own (London: Chatto & Windus, 1934).

13. Marion Milner, On Not Being Able to Paint (London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1950).

14. Anne Truitt, Day Book: The Journal of an Artist (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982).

15. Catherine M. Soussloff, The Absolute Artist: The Histiography of a Concept (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

16. Gerald Wilkinson, Turner’s Early Sketchbooks: Drawings in England, Wales and Scotland from 1789 to 1802 (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1972).

17. Arnold Glimcher and Marc Glimcher, Je suis le cahier: The Sketchbooks of Picasso (New York: The Pace Gallery, 1986), 2, 3.

18. ‘Donald Rodney’s Sketchbooks,’ at Tate, accessed 14 July, 2017, at http://www2.tate.org.uk/donaldrodney/sketchbooks.htm; ‘Turning The Pages – Helen Chadwick’s Notebooks,’ at Henry Moore Foundation, accessed 18 June, 2017, at https://www.henrymoore. org/archives-and-library/sculptors-papers-archive/turning-the-pages—helen-chadwicks-notebooks.

19. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commonplace_book, accessed 30 June, 2017.

20. ‘Newton Papers,’ accessed 30 June, 2017, at https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-03996/9.

21. Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend (New York: Europa Editions, 2012); Elena Ferrante, The Story of a New Name (New York: Europa Editions, 2013); Elena Ferrante, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (New York: Europa Editions, 2014); Elena Ferrante, The Story of the Lost Child (New York: Europa Editions, 2015), 310.

22. Felicity Allen, ‘CREATIVITY v EDUCATION’, Art Monthly 366 (2013): 12.

23. For example, see: Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex [1949] (London: Penguin Books, 1979), 17.

24. Patti Lather, Getting Smart: Feminist Research and Pedagogy With/in the Postmodern (New York: Routledge, 1991), xvi.

25. Oxford English Living Dictionary, accessed 10 April, 2017, at https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/research.

26. Whilst developing my thoughts for this essay, I heard a national radio broadcast that crystallized what I am calling here my antagonism. A celebrity punk star, once perceived publicly as a bête noir, when being interviewed about his creative process stated without being challenged: ‘Nature gave me the gift to be able to look at myself from the outside in’. John Lydon, ‘Simon Mayo Drivetime,’ BBC, London, Radio 2, 27 Mar, 2017.

27. Penny Jane Burke, ‘Writing, Power and Voice: Access to and Participation in Higher Education,’ Changing English 15:2 (2008): 204. The final section is a quotation from Patti Lather.

28. Patti Lather, ‘Against Proper Objects: Toward the Diversely Qualitative’, paper presented at Summer Institute in Qualitative Research: Putting Theory to Work, Manchester Metropolitan University, Education and Social Research Institute, 6–10 July, 2015, accessed 2 August, 2017, at http://www.esri.mmu.ac.uk/siqr/archive15.php.

29. Patti Lather, ‘FERTILE OBSESSION: Validity After Poststructuralism,’ The Sociological Quarterly 34:4 (1993): 674.

30. Lather, Getting Smart, xv.

31. The BBC archive attributes its inception of British sculpture to the work of Jacob Epstein, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, see BBC, ‘British Sculptors: Artists in Stone, Metal and Wood,’ accessed 21 August 2017, at http://www.bbc.co.uk/ archive/sculptors/. In 1977, art critic William Packer wrote: ‘It…is now accepted by many people, sculptors among them, that the last twenty-five years or so have seen a remarkable renaissance of sculpture in this country and the establishment of a national school second to none in the world’, and see: GLC London Celebrations Committee for The Queens Silver Jubilee, A Silver Jubilee Exhibition of Contemporary British Sculpture 1977, (London: Mathews, Miller Dunbar: 1977), 2. In recent research the term ‘sculpture in Britain’ is used, see: Lisa Le Feuvre, United Enemies: the Problem of Sculpture in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s (Leeds: Henry Moore Foundation, 2011), 4.

32. Lather, Getting Smart, xv.

33. A useful description of the relationship between British sculpture and English art colleges can be found in Lynne Cooke, ‘Between Image and Object: the “New British Sculpture’’,’ in A Quiet Revolution: British Sculpture Since 1965, ed. Terry A. Neff (USA: Thames and Hudson, 1987). This essay mentions the work of twenty-five sculptors to present a scene of ‘New British Sculpture’ but only two of these are women.

34. Beverley Skeggs, Formations of Class & Gender: Becoming Respectable (London: Sage, 1997), 1.

35. Rebecca Fortnum, ‘Creative Accounting: Not Knowing in Talking and Making,’ in On Not Knowing: How Artists Think, ed. Elizabeth Fisher et al. (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2013), 70–86.

36. Idem, 70.

37. Basic Design was considered a new and radical approach to training in British Art Schools in the 1950s and 1960s, and is believed to have been influential in the character of art college teaching in Britain since. The curriculum was delivered teaching through a series of tutor led exercises and tasks that addressed what were believed to be the fundamentals of all art and design, e.g. line, shape, colour, tone, texture. The Basic Design approach aimed to shatter students’ expectations and preconceptions previously learnt and dispel divisions between Fine and Applied Arts. Although retrospectively criticized for lacking to recognize students as human beings in social relationships, the approach can still be found to underpin the preliminary year to studying art at BA (Hons) level in the UK (known as a Foundation course). Leeds Arts University (formerly Leeds College of Art) is one such institution that still aligns its Foundation year curriculum to Basic Design. See: ‘Leeds Arts University Foundation Diploma in Art & Design,’ accessed 26 August, 2017, at http://www.leeds-art.ac.uk/study/further-educa tion-courses/foundation-diploma-in-art-design/.

38. Fortnum, ‘Creative Accounting,’ 70.

39. Idem, 72.

40. This is a description I have used myself. I have found it used in a similar way to describe ‘an emerging creative splurge’ in Sujat Maharaj, ‘What the Thunder Said: Toward a Scouting Report on “Art as a Thinking Process’’,’ in Mara Ambrožič and Angela Vettese, Art as a Thinking Process: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 155.

41. The relationship between psychoanalysis and feminism in this period is well articulated, see: Sonya Andermahr, Terry Lovell, and Carol Wolkowitz, A Glossary of Feminist Theory (London: Arnold, 2000), and Griselda Pollock, Differencing The Canon (Abingdon: Routledge, 1999).

42. Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta and Tere Vadén, ‘Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public’ in The Critical Qualitative Research Series, ed. Shirley R. Steinberg and Gaile S. Canella, vol. 15 (New York: Peter Lang, 2014), ix.

43. Idem, 4. This text acknowledges its debt to Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s work on indigeous research methodology. See: Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2012).

44. Life writing is autobiographical writing which engages with matters greater than the personal. Sheila Gaffney, ‘A Story Within a Story Within a Story Within a Story: British Art School Experience Retrieved Through Archive, Anecdote and Life Writing,’ n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal 40 (2017): 80.

45. Rowan Bailey, University of Huddersfield, ‘Thought Positions in Sculpture,’ accessed 21 August, 2017, at https://research.hud. ac.uk/institutes-centres/st/thoughtpositionsin sculpture/rowanbailey/#/rowan-bailey-iii.

46. Object Relations Theory was a British development of Freudian psychoanalytical theory during the 1940s and 1950s. See: Lavinia Gomez, An Introduction to Object Relations (London: Free Association Books, 1997).

47. Christopher Bollas, The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known (London: Free Association Books, 1987), 2.

48. Ibidem.

49. Idem, 42.

50. Idem, 280.

51. Idem, 10.

52. I am thinking of Alex Potts’ statement that ‘a distinctively modern sculptural imaginary began to define itself as a result of developments in the eighteenth-century art world’ in his introduction to The Sculptural Imagination: Figurative, Modernist, Minimalist (New York: Yale University Press, 2000), 1.

53. Lather, ‘FERTILE OBSESSION’, 676.

54. This is my own observation after many years of working in higher education with students in art colleges, and mentoring emergent artists for small arts organisations, before the art they make becomes part of public knowledge. The art we experience, and particularly that which is deemed significant, is always mediated, prior to our encounters with it. Curatorial practice is an example of a constitutive agenda within the production of the cultural phenomena of exhibition, that takes place to enable comprehensive public facing presentation of creative practices. See: Judith Rugg and Michèle Sedgwick, Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2007).

55. Lather, ‘FERTILE OBSESSION’, 687.

56. Idem, 685.

57. Ibidem.

58. This quotation attributed to Derrida (1997) is frequently quoted to explain Ironic Validity.

59. Pete Docter, dir., Inside Out, 3D computer animated film (USA: Pixar Animation Studios, 2015).

60. Lather, ‘FERTILE OBSESSION,’ 673.

61. Lather, Getting Smart, xvii.

62. The development of theoretical resources since the 1970s now enable Hesse’s work to be read differently. However, the materials I have listed remain the same source for such enquiries. In the catalogue for the 2002 exhibition at Tate, Gioa Timpnelli discusses her diaries, and Elisabeth Sussman’s quoted statement for the symposium Encountering Eva Hesse, AHRC Centre CATH and Tate Modern, November 2002 lists her sources (Pollock and Corby, Encountering Eva Hesse, 23). See: Gioa Timpanelli, ‘Woodstock Paintings,’ in ed. Elisabeth Sussman, Eva Hesse 1936–1970 – Exhibitions (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).