Poetic Effects of Language Theories

Alícia Fuentes-Calle

To cite this contribution:

Fuentes-Calle, Alícia. ‘Poetic Effects of Language Theories.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/poetic-effects-language-theories/.

GLOSSARY

Cognitive semantics

The theoretical approach of Len Talmy. According to Talmy, cognitive semantics deals with conceptual material and its organisation in language. Two complementary systems are established: the lexical (conceptual content), and the grammatical (conceptual structure). Conceptual organisation is explored both at a general level, and through a set of particular domains: space and time, causation, motion, attention, viewpoint, etc. This approach is adopted by this text.

Jakobson, Roman

(1896–1982), became one of the most influential linguists of the twentieth century by pioneering the development of structural analysis of language. Jakobson defends the inseparability of poetics from the rest of linguistics, and argues that the poetic function (one of the functions of language postulated by him) must be regarded as an implicit element of every verbal activity: ‘Poetic function is not the sole function of verbal art but only its dominant, determining function, whereas in all other verbal activities it acts as a subsidiary, accessory constituent’.1 The poetic function of language is, therefore, not to be related to poetry alone, but needs to be adopted as a perspective on language in general.

Metalinguistic

Metalanguage: language about language. Awareness of the nature of language.

Poetic effects

Poetics is understood here as a technology that empowers perception and experience via language. What dimensions of language can be poetically activated, what we think language is, and what can be done with language, are also part of our poetic investigation. Besides, as Alastair Pennycook suggests, there is a ‘need to rethink the relations between languages, humans, and objects: there is no longer a world “out there” separate from humans and represented in language but rather a dynamic interrelationship between different materialities’.2 In this framework, a continuum of poetic effects is suggested. Poetics is understood here as a matter of degree, latent in any linguistic-communicative manifestation. Poetic effects are the ways by which the different poetic levels (as those postulated in this text: Poetics I, Poetics II) are perceived, cognized, and/or experienced.

Poetics of knowledge

Understood here as implied by the question: ‘Is there in some kindred sense “a poetry, a music of thought” deeper than that which attaches to the external uses of language, to style?’.3

Talmy, Len

Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. His broader research interests cover cognitive linguistics, the properties of conceptual organisation, and cognitive theory, with additional specialisations in American Indian and Yiddish linguistics. Virtually all his written work is available on his website.4

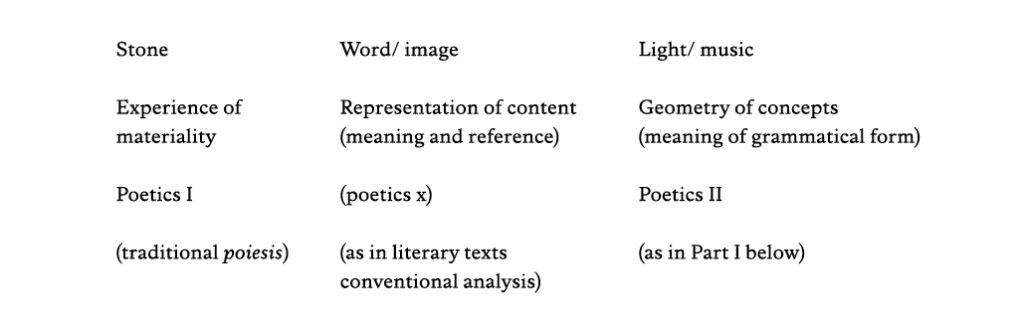

Stone, word, light

In ‘Coleridge’s Dream’ (1951), Jorge Luis Borges draws on the story of the poem Kubla Khan, dreamt, and then partially recalled and transcribed, by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, on a summer day in 1797. Coleridge had been reading a passage in Samuel Purchas’s Purchas his Pilgrimage about the construction of a palace by the thirteenth century Mongolian emperor Kublai Khan (‘In Xamdu did Cublai Can build a stately palace…’), when he fell asleep. The reading consequently transmuted into dreamed images and these in words, all in all, Borges states, ‘fifty-odd rhymed and irregular lines of exquisite prosody’.

Although the whole poem could not be recalled on waking by Coleridge, ‘Swinburne5 felt that what he had been able to recover was the supreme example of music in the English language, and that the person capable of analyzing it would be able – the metaphor is Keats’ – to unravel a rainbow’.6

That dream, though, appeared to be inscribed in a historical sequence – in some events preceding, even announcing it. According to Borges, the vizier of Ghazan Mahmud reported in the fourteenth century’s Compendium of Histories by Rashid al-Din that Kublai Khan had built a palace according to a plan that he had seen…in a dream.

A metamorphic architecture seems to evolve in time, ranging from the palace of stone (via Khan’s dream) to the palace of light/music (as Swinburne puts it, through Keats’ metaphor), via the palace of words, which is the poem triggered by Coleridge’s dream. ‘[T]he palace;… the poem. Whoever compares them will see that they are essentially the same’, Borges underscores.

The sequence would not be just a chain of ekphrasis (i.e. of expression of an artistic concept in different media, an interartistic mode of transfer),7 but of transubstantiation – a sequence of different objects. An extreme case of poiesis. Not a verbal representation of the stone palace, but the same palace made out of words, then made out of light. Poetic effects in an extreme degree.

A continuum of poetic effects could be suggested as follows: Poetics I, poetics as poiesis, in its original aim as performative, transforms the world. ‘The first dream added a palace to reality’.

Poetics I, poetics as poiesis, in its original aim as performative, transforms the world. ‘The first dream added a palace to reality’.

Poetics(x), in its undefined culturally, historically situated manifestation. In western tradition, generally framed in literary texts: mental representations involved in experiencing a work of literature, as a work of literature.8

I introduce in this text the notion of Poetics II. It activates the poetic effects latent in linguistic theory. In the knowledge emerging from the properties of language, made explicit through theoretical constructs. A manifestation of the poetics of knowledge. ‘[T]he person capable of analyzing [Coleridge’s poem] would be able…to unravel a rainbow’.

And hence, we could even read in the continuum the progression from stone to light, operated by word, through the technology provided by poetics.

Poetics I, the closest to the original poiesis, uses language as an ephemeral vehicle and gets rid of it after a while, as if throwing off silk clothes or spitting out sunflower seed shells – to be left with its effects, its material outputs.

Poetics II, at the other extreme of the continuum, exhibits language scaffolding for extreme perception and for its intrinsic effects, for the eloquence of its very nature – as latent harmony made visible in the silent non-musical contemplation of sheet music.

Poetics II is suggested in this text as a locus to explore uncharted resources for the art of language. Resources provided by linguistic theories that unravel elements and properties of language. My interest is not, therefore, in ‘literary texts’, but in a broader exploration of the poetic effects triggered by linguistic theoretical constructs. These, it is argued, could be included in a somehow enlarged art of language.

*

Linguistic autobiographies can be engaging stories about how several languages are managed in globalising lives. They are, at times, surprising accounts of intercultural acrobatics, and of emotional entanglement. They can be seen, in a good part, too, as narratives on fictions – metaliterature on those objects called languages, which were invented (as fictions) at some point in history (to be learnt, to be counted, to be dispossessed, to be used).

I have a linguistic autobiography, as everyone else. As a child becoming soon bilingual (…), curious about people talking so differently across Europe (…), soon after engaging in learning (…),9 and becoming familiar with many diverse systems of meaning and structures. Soon realizing that there is more to language than patterns of forms and choreographies of meaning. Those formal descriptions called languages were just arbitrary abstractions out of the actual communication magma in which humans engaged. Fascinated by that theory part, however. And seeking to translate it into other forms. Other forms also given to contemplation (as in theoria), as was grammar.

That is where my linguistic autobiography, rather than in the accumulation of ‘languages’ of the world, properly starts. Following Roman Jakobson, on one hand, for whom ‘poetics makes all levels of language resonate’ – an inclination to look at linguistic theory through the glass of its potential poetic effects. In accordance with Victor Yngve,10 and many others, on the other hand, ready to accept language and grammar as ‘theories of theories’, ‘representing imaginary objects’, ’fictions’.

In autumn of 2005, I was reading again ‘The Relation of Grammar to Cognition’, by Len Talmy.11 The reading-meditation would automatically return the particular theoretical approach offered by the author back to my mind as a poetical device per se.

This paper approaches the entanglement of language and poetics suggested by Jakobson (‘poetics may be regarded as an integral part of linguistics’) beyond officially poetic manifestations. This invites us to experimentally address, it is suggested in this text, the poetic activation of the properties and principles of language postulated by linguistic theory.

As stated above, the focus of this text is not on ‘literary texts’, but on a broader exploration of the poetic effects of the theories of language. Poetic effects triggered by theoretical constructs. Poetic effects that could be included in a somehow enlarged art of language. An art of language understood as an unprejudiced exploration of what are languages, what can we do with them.

In this text I assume that the potential of the art of language depends to a large extent on the knowledge we have of the elements and variables that make up this art:

- Our knowledge on the locus of poetic activation, on the one hand, for example, the elements and properties of the language.

- On the other hand, the beliefs we maintain about what language and ‘languages’ are and what can be done with them (scope of possibility and restriction).12

Being aware of such beliefs (also known as ‘linguistic ideologies’) appears to be crucial to engage both in a sound exploration of the art of language, and in critical (meta)linguistic autobiographies. Both are, in fact, deeply interrelated.

PART I

On indolens Grammar (indŏlens, (Lat.) not suffering, insensitive to pain)

Icarus

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus13

William Carlos Williams, 1883–1963

According to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was spring

a farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantry

of the year was

awake tingling

near

the edge of the sea

concerned

with itself

sweating in the sun

that melted

the wings’ wax

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

a splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning14

This text is an experiment on poetics as a perspective on language theory. An experiment on mining poetic resources that are latent in less charted theory sites. Largely with Jakobson in mind:

‘poetics may be regarded as an integral part of linguistics’

‘the scrutiny of language requires a thorough consideration of its poetic function’

‘poetic language makes all levels of a language resonate’.15

It is assumed in this text that poetics is a point of view on language that tends to raise its properties to the maximum exponent. Poetics could be seen as a technology to enhance perception and acknowledge, therefore, that it is through the poetic dimension of language that its specific properties and elements are manifested more clearly.

This perspective, although briefly and at a greatly reduced scale, will be applied in this text to some notions proposed in the framework of cognitive semantics. Namely the cognitive semantics field as approached by Talmy in the chapter ‘The Relation of Grammar to Cognition’, to which I refer earlier. Some sections in that chapter will be used as a bank of data to engage in the poetic activation of elements of linguistic theory: namely, the meaning encoded in grammatical elements (as opposed to lexical elements). Mainly the constraints to their meaning, as they are described by Talmy, i.e. that which is left unsayable due to the particular properties and constraints making up human languages.

*

Following the inverse sense of Paul Kiparsky’s statement that ‘the linguistic sames which are potentially relevant in poetry are just those which are potentially relevant in grammar’,16 this exercise will explore how some grammatical properties and patterns postulated by Talmy can actually be experienced as poetic insights that can be traced through some overtly literary manifestations.

It is suggested here, resonating with the words of Jakobson and Kiparsky, that the plausibility of postulated linguistic constructs be tested relative to their efficacy as generators of ‘poetic effects’ – effects felt as cognitive experiences triggered by gazing at (as in theoria, contemplation) diverse perspectives in parallel; epistemic pleasure via metalinguistic awareness; poetic awareness via metalinguistic knowledge.

*

Using Talmy’s analysis, we can identify a phenomenon, described in this text as semantic indolentia, in some territories of grammatical meaning. The origin of indolentia resides in the quality of being indŏlens: (Lat.) not suffering, insensitive to pain – a qualified sort of obliviousness. For example, this quality is specified by a series of neutralities in the way the grammatical elements of languages convey magnitude. Neutralities in the sense that some linguistic forms in charge of conveying conceptual structure show no variation whatsoever that correlates to the variation of certain aspects of the meaning they communicate. The author so offers an example similar to this one:

This freckle is smaller than that freckle

This planet is smaller than that planet.

Freckles and planets differ substantially in size, shape, and degree of intimacy relative to the speaker. Nevertheless, the grammatical scaffolding provided by this-that is oblivious to those differences (indolens), and hence maintained identical in both cases.

These neutralities are explained, apparently, as a manifestation of the universal inclination of languages to express topological (space as distributed in regions, points located in areas) instead of Euclidian reference (where distinctions regarding distance, size, shape, etc. are made). In other words, a preference is shown in the grammar to convey relative rather than absolute, fixed quantities.

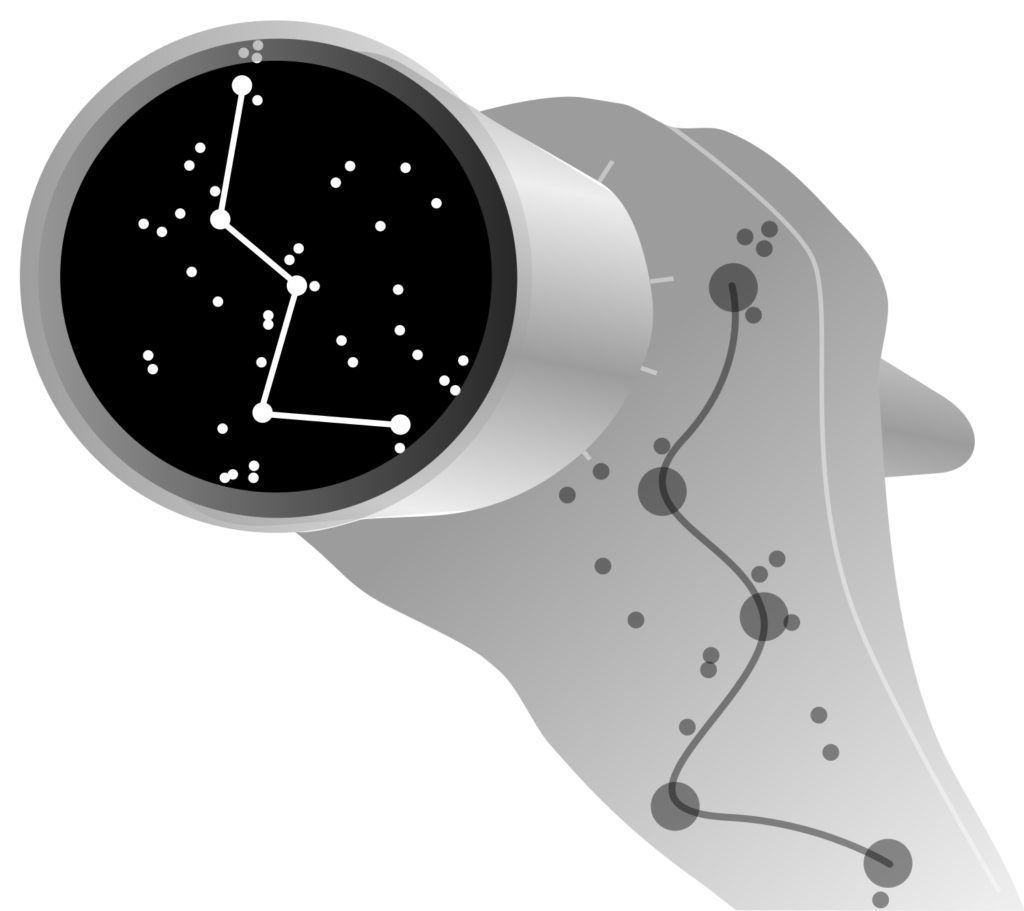

This theoretical finding by Talmy, it could be said, generates poetic effects by evoking interscalar perspective. Correspondence between microscopy and macroscopy via grammatical elements. More precisely, via differential meaning non-possibly expressed by grammatical elements but made visible through theory.

A related poetic effect of the interscalar perspective is actually conveyed by Italo Calvino in one of his invisible cities:

Con tale arte fu costruita Andria, che ogni sua via corre seguendo l’orbita d’un pianeta e gli edifici e i luoghi della vita in comune ripetono l’ordine delle costellazione e la posizione degli astri più luminosi…17 [Andria was built so artfully that its every street follows a planet’s orbit, and the buildings and the places of community life repeat the order of the constellations and the position of the most luminous stars…]

Implicit and potential poetic effects dwell in the constraints of grammatical meaning as it can be made visible by theory – it ‘gives to be seen the unthought in our thought’.18 Theoretical constructs that explore the grammatical scaffolding resonate, as concepts, in the poetics freely expressed by the art of language. In this text I offer so-called ‘literary’ examples from Calvino and Borges.

Apparently, one domain of what is semantically constrained in grammatical form, the unsayable, finds its way in poetic awareness. Neutralities, indolentia, are expressed via ‘officially’ poetic (i.e. literary) manifestation.

Alícia Fuentes-Calle, Interstellar, digitally produced image.

Grammatical elements are those responsible for the conceptual structure (i.e. the scaffolding of our expression, as opposed to the conceptual content, conveyed by freer elements such as nouns, verbs, etc.). According to Talmy, this structure of the world’s cognitive representations in schematic terms of time/space (matter/ action) is largely relativistic, topological, qualitative or approximative, rather than absolute, Euclidean, quantitative or exact. It results in allowing us no distinction between our grammatical expression of freckles, streets and planets. As if revealing a sort of equivalence between them at a certain level of perception. As it is poetically done by Calvino, via Andria.

(Openly) Indolens Grammar

Another example. Grammatical forms refer to types or categories of phenomena, not to specimens, tokens or individuals in particular. Individual identity can be grammatically ignored.

Thus, unlike the usual distinction between common names (to refer to types, ‘cousins’) and proper names (in reference to tokens, ‘Angelica’), we would not find ‘proper prepositions’ to mark ‘a unique spatiotemporally bounded phenomenon’,19 that is, a token action. Forced, as we are, by language not to express a distinction between Jesus walked up the hill named Calvary, and Joan walked up the hill last Friday.

Conventional use of language would not accept *Jesus walked Astation the hill named Calvary, inventing the ‘proper preposition’ Astation to cater for the need of expressing how exceptional the fact was.

We can probably think of fervent believers feeling the true need to single out unique, spatiotemporally-bounded phenomena belonging to their own sacred histories and geographies. Those which are experienced not in terms of ordinary chronology or geography, but in a sense of time closer to the notion of khairos (a qualitative, sacred approach to time) as opposed to the quantitative experience of chronos.

The meaning captured by this level of indolentia (via invariability) of the conceptual structure might be one of those instances where unsayability is more clearly realised. As a certain no.st.algia (‘the.pain.for.not.being(there)’), a slight suffering for what is absent, sensed by linguistic creatures. A certain degree of awareness of the fact that grammar is somehow blind to phenomena felt as exceptional – a poetic awareness.

This particular region of awareness is to be found in frequent poetic expressions of a certain kind. It manifests perplexity and strangeness about the indifference of the world, which perseveres in its invariable structure, indolens, after someone is dead:

The planet turns there without you, beautiful.

Exiled by death you cannot

touch it. Weird joy to watch postulates

lived out and discarded, something crowded

inside us always craving to become something

glistening outside us, the relentless planet

showing itself the logic of what is

buried inside it. To love existence

is to love what is indifferent to you

you think, as you watch it turn there, beautiful.

…

Frank Bidart20

*

Or in the poetic expression of the indifference shown by the world, through the invariability of its grammar – grammar of landscape and labour cycles. Indolentia regarding extraordinary events, even those of mythical proportions, such as The Fall of Icarus. In William Carlos Williams’ poem dedicated to the painting attributed to Pieter Brueghel, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (De val van Icarus) that opens this section.

Upward, Behind the Onstreaming It Mooned

From a certain perspective, we find, at least, two categories of languages:21

Languages that refer to objects and substances with nouns. They are the majority. They prototypically construct the reference of physical objects and substances through their tangible materiality. ‘Bell’ is a noun. ‘Language’ is a noun. We reify languages. They are invented, enumerated, possessed and dispossessed, administered, fixed. Like objects can be. See Part II.

Languages that refer to objects and substances with verbs. Verbs are usually associated to action, movement, process. If ‘language’ were a verb. Disinvention. See Part II.

In Talmy we are presented with with an actual example of this category – from Atsugewi (a Hokan language of Northern California):22 ẃoswalaka.

Literally:

‘a-flexible-linear-object-is-located on-the-ground because-of-gravity-acting-on-it’.

Or, to emphasise the fact that the object, the rope, is conceptualised not with a noun, but with a verb:

‘itgravitically-linearises-aground’.

Meaning:

‘There’s a rope lying on the ground’.

Step by step:

wo– ‘as a result of gravity/ an object’s own weight acting on it’.

swal– ‘for a flexible linear object to move/ be located’. The verb root that the language uses to construct the concept of ‘rope’.

ak– ‘on the ground’.

Atsugewi also has somenouns (naha’head’).

Most of them, however, are derived from verbs.

That is the case for ‘sun/moon’, ćnehẃu.

It comes from the verbal root–hẃu–, ‘to describe an arc across the background of the sky’.

*

Let’s visit now the fictional world of Tlön in ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, by Jorge Luis Borges.23 As far as the southern hemisphere of Tlönis concerned:

The nations of this planet are congenitally idealist. Their language and the derivations of their language – religion, letters, metaphysics – all presuppose idealism. The world for them is not a concourse of objects in space; it is a heterogeneous series of independent acts. It is successive and temporal, not spatial. There are no nouns in Tlön’s conjectural Ursprache, from which the ‘present’ languages and the dialects are derived: there are impersonal verbs, modified by monosyllabic suffixes (or prefixes) with an adverbial value. For example: there is no word corresponding to the word moon, but there is a verb which in English would be ‘to moon’ or ‘to moonate’. ‘The moon rose above the river’ is hlör u fang axaxaxasmlö, or literally: ‘upward behind the onstreaming it mooned’.

The preceding applies to the languages of the southern hemisphere. In those of the northern hemisphere…the prime unit is not the verb, but the monosyllabic adjective. The noun is formed by an accumulation of adjectives. They do not say ‘moon’, but rather ‘round airy-light on dark’.

Su lenguaje y las derivaciones de su lenguaje – la religión, las letras, la metafísica- presuponen el idealismo. El mundo para ellos no es un concurso de objetos en el espacio; es una serie heterogénea de actos independientes. Es sucesivo, temporal, no espacial. No hay sustantivos en la conjetural Ursprache de Tlön, …: hay verbos impersonales, calificados por sufijos (o prefijos) de valor adverbial.

Por ejemplo: no hay palabra que corresponda a la palabra luna, pero hay un verbo que sería en español lunecer o lunar. Surgió la luna sobre el río se dice hlör u fangaxaxaxasmlö o sea en su orden: hacia arriba (upward) detrás duradero-fluir luneció. (Xul Solar traduce con brevedad: upatrasperfluyelunó. Upward, behind the onstreaming it mooned.)

En el hemisferio boreal: ‘… la célula primordial no es el verbo, sino el adjetivo monosilábico’. El sustantivo se forma por acumulación de adjetivos. No se dice luna: se dice aéreo-claro sobre oscuro-redondo.

Borges believes in genres to the extent that they channel an expectation:

I think that they do exist to the extent that there is an expectation on the part of the reader. I think that a person reads a short story in a different way than they do when they read an entry in an encyclopaedia, or when they read a novel, or when they read a poem.

Grammatical categories, such as nouns and verbs, can also be used as genres. The linguistic expectations that they generate from most (Indo-European) languages (N: object, V: action) can be violated for the benefit of poetic effects.

BORGES VALIDITY STATEMENT

‘The metaphysicians of Tlön do not seek for the truth or even for verisimilitude, but rather for the astounding. They judge that metaphysics is a branch of fantastic literature’.24

*

Borges wrote ‘Tlön, Uqbar, OrbisTertius’ in 1944. Descriptions of North American languages were already available (as we know from the works of North American linguists and anthropologists Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, Benjamin Lee Whorf and others). The question remains as to whether Borges had access to those sources or not. It can be deemed probable given his avid reading of science and anthropology, as well as his Anglophone inclination. Alternatively, it can be hypothesized that he generated these poetic linguistic fantasies from the philosophical systems of his interest (Idealism, among others). In any case, the theoretical reason of Talmy and the poetic reason of Borges coalesce in one shared image: the moon as a verb.

*

This text has introduced an exploration of how some grammatical properties and patterns postulated by Talmy can actually be experienced as poetic insights that can be traced in some overtly literary manifestations. It has been introduced here a particular approach to the entanglement between poetics and linguistics, strongly emphasised by Jakobson. More so, it is suggested that the plausibility of postulated linguistic constructs be tested relative to their efficacy as generators of ‘poetic effects’.

‘Poetic effects’ felt as cognitive experiences triggered by gazing at (as in theoria, contemplation) diverse perspectives in parallel. Epistemic pleasure (conceptual estrangement and joy) via metalinguistic awareness. Poetic awareness via our experimentation with concepts.

PART II

[N]ot a matter of looking harder or more closely, but of seeing what frames our seeing – spaces of constructed visibility and incitements to see which constitute power/knowledge.25

[W]e want to propose neither a view that we need better descriptions, nor mere acknowledgement of fuzziness, but instead strategies of disinvention and reconstruction.26

Languages are inventions. Makoni and Pennycook address some of the key elements of the critical linguistic approach.27 Languages were invented, dialectically co-constructed with nations.

We could argue the reciprocal invention of endangered and dangerous languages. Dialectical co-construction of anthropos and humanitas, a hierarchy of languages translated into cultures (channelled by those many small, local and usually endangered languages; languages and knowledges usually addressed by Anthropology), and Knowledge (the one that normally feeds the Humanities) – a double standard in the history of knowledge, eventually translating into a double standard of the very human being: anthropos and humanitas, as Nishitani Osamu puts it.28

Linguistic construction. Languages conceived of as bounded objects – physically located, countable entities. A conception in terms of what it was believed possible to do with languages. At its turn, shaping our potential as linguistic beings.

Invention of a metalanguage. Languages are theories of theories. According to Yngve, ‘Being fictions, they are not the sorts of things that could be innate…One cannot have a science that invents its own objects of study and introduces them by assumption’.29 Yngve attributes the impossibility of a plausible body of knowledge to language per se, and postulates what he terms a human linguistics rather than a linguistics of language.30

Reconstruction:

Metadiscursive regimes used to describe languages are located in Western linguistic and cultural suppositions. They do not describe a real state of affairs in the world, they are not natural kinds: they are convenient fictions (to the extent that they provide a useful way of understanding the world and shaping language users), and inconvenient fictions to the extent that they produce particular and limiting views on how language operates in the world (Makoni and Pennycook).31

I.e. On what can be perceived, cognized, experienced and done via language.

An alternative conceptual repertoire about language seems to be needed. Since our concepts both constrain and enlarge our potential as humans, specific attention can be paid to the multiple ways of knowledge production. Experimental forms of practice, and their derived new ways of knowing, might generate new ontological objects or relations, even in linguistic theory. This text has emphasised some experiments on epistemic pleasure (conceptual estrangement and joy) via metalinguistic awareness – poetic awareness via our experimentation with linguistic concepts.

The inertia of verbal art as based on languages has given to the world thousands of monolingual literary works out of bounded reified languages (in their nation-bounded correctness), for the most part describable through the lenses provided by descriptive and structural linguistics.

Raising verbal art to less visited powers will depend on broadening the scope of the elements and properties of language and communication to be activated for poetic effect.

Approaching the theory of language from this perspective, assessing its validity according to poetic efficacy, might contribute to this direction. Validity via experiments on linguistic theory that open spaces of visibility to potential poetic effects.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is assumed in this text that the potential of the art of language depends to a large extent on the knowledge we have of the elements and variables that make up this art, i.e., the elements and properties of the language. We have looked at some specific examples in Part I. On the other hand, the beliefs we maintain about what language and languages are, and what can be done with them. This set of beliefs, also known as ‘linguistic ideology’, is a crucial part of a critical (meta)linguistic autobiography.

I raise the question here of the extent to which the art of language can covariate with the state of linguistic theories, and how the potential poetic activation (in the sense sketched in this text) of these theoretical constructs can be assessed as an index of their validity. Once we realise to what extent languages have been inventions, fictions, and hence, to what extent linguistic theories are theories about theories (i.e. with no actual reference), we raise the issue of seeking the validity of those theories in their capacity to generate poetic effects.

The development of the art of language and its innovations will therefore depend on a transformation of beliefs about what can be activated poetically. Broadening its potential depends, to a large extent, on the knowledge we have of the locus that can be activated poetically (that is, of the elements and properties of the language postulated by theoretical constructs).

It is in this key that we reread the imperative formulated by Jakobson, where the author insists on the necessary correlation between poetics and linguistics:

Poetics deals with problems of verbal structure…Since linguistics is the global science of verbal structure, poetics may be regarded as an integral part of linguistics.32

‘[P]oetics may be regarded as an integral part of linguistics’ and even, as it has been suggested in this text, contribute to test the validity of linguistic theories.

[C]ertain artists…are unconsciously striving for a generalized art language…Their art expression is frequently strained, it sounds at times like a translation from an unknown original – which, indeed, is precisely what it is.

These artists…impress us rather by the greatness of their spirit than the felicity of their art. Their relative failure is of the greatest diagnostic value as an index of the pervasive presence [in the art of language] of a larger, more intuitive linguistic medium than any particular language.33

1. Roman Jakobson, ‘Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics,’ in Style in Language, ed. Thomas Albert Sebeok (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960), 350–77.

2. Alastair Pennycook, ‘Posthumanist Applied Linguistics,’ Applied Linguistics (2016).

3. George Steiner, The Poetry of Thought: From Hellenism to Celan (New York: New Directions, 2011), 12.

4. http://linguistics.buffalo.edu/people/faculty/talmy/talmyweb/index.html, accessed 1 May, 2017.

5. Borges refers to Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909), English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic.

6. Swinburne sintió que lo rescatado era el más alto ejemplo de la música del inglés y que el hombre capaz de analizarlo podría (la metáfora es de John Keats) destejer un arco iris. Borges, ‘El sueño de Coleridge,’ in Otras disquisiciones [1952] (Barcelona: Destino, 2007).

7. See, for example, Siglind Bruhn, Musical Ekphrasis: Composers Responding to Poetry and Painting (Hillsdale: Pendragon Press, 2000).

8. Adrian Pilkington, Poetic Effects: A Relevance Theory Perspective (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2000).

9. Ellipses account for predictable variables to be filled differently in different contexts, such as bilingual (Spanish/Catalan in my case), across European cities, regions, countries, communities, etc, and learning (the languages of one’s choice). Linguistic biographies are almost invariably grounded on those (nation-state based) artefacts called languages.

10. Victor Yngve, ‘An Introduction to Hard-Science Linguistics,’ in Hard-Science Linguistics, ed. Victor Yngve, et al. (New York: Continuum, 2004), 27–35.

11. Len Talmy, ‘The Relation of Grammar to Cognition,’ in Toward a Cognitive Semantics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), 21-55.

12. Alícia Fuentes-Calle, Art del llenguatge i diversitat lingüística. De R. Jakobson a L. Talmy i É. Glissant, PhD thesis online (Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, 2016), accessed 1 May, 2017, at http://hdl.handle.net/2445/101752.

13. William Carlos Williams, Collected Poems: 1939–1962, Volume II (New York: New Directions, 1962).

14. Please view Pieter Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, c. 1558 at http://artchive.com/artchive/b/bruegel/icarus.jpg.html (The Artchive, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels).

15. Jakobson, ‘Closing Statement’.

16. Paul Kiparsky, ‘On Theory and Interpretation,’ in Linguistics and Literary Theory, ed. Derek Attridge, et al. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987).

17. Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili (Verona: Oscar Mondadori, 1993), 150.

18. Patti Lather, ‘Fertile Obsession: Validity After Poststructuralism,’ The Sociological Quarterly 34:4 (1993): 673–93.

19. Talmy, ‘The Relation of Grammar,’ 32.

20. Frank Bidart, ‘Visions at 74‘ (2015), Poetry Now, accessed 1 March, 2017, at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/58042/visions-at-74.

21. Talmy, ‘The Relation of Grammar,’ 45–46.

22. Ibidem.

23. Borges, ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,’ in Labyrinths, trans. Donald Yates and James Irby (New York: New Directions, 2007).

24. Ibidem.

25. Lather, ‘Fertile Obsession,’ 675.

26. Sinfree Makoni and Alastair Pennycook, Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2007), 27.

27. Ibidem.

28. N. Osamu, ‘Anthropos and Humanitas: Two Western Concepts of “Human Being”,’ in Translation, Biopolitics, Colonial Difference, ed. Naoki Sakai and Jon Solomon (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006), 259–74.

29. Yngve, ‘Introduction to Hard-Science,’ 34.

30. Idem, 28.

31. Makoni and Pennycook, Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, 27.

32. I reread this through P. Kiparsky’s proposal. Kiparsky (1987) (cf. note 14) argued that Jakobson’s programme is still valid as long as it is revisited through contemporary linguistic theory. While Kiparsky was most probably referring to the theory of universal grammar, I have suggested here using experimentally a specific version of cognitive semantics.

33. Edward Sapir, Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921), 220.