‘On/Off-Message’

Joey Bryniarska & Martin Westwood

To cite this contribution:

Bryniarska, Joey and Martin Westwood. ‘”On/Off-Message.”’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/on-off-message/.

‘Crawl-Space’ and the crawl space

Between the cracked skin of a concrete pachyderm and a gabled copper hat lies the crawl space. The crawl space has an animal’s conception of time; a pace matched by its own creeping metabolism of stone and plaster. The crawl space is not public, nor is it private, but is somewhere porously in between; a century’s worth of faeces, spider webs and feathers plus grey sand jet-blasted from restoration works, coats the interior in a fine, consistently grey powder…The basilica’s true form is concealed; underneath its A-frame roof in fact lies a colossal cruciform flatworm, segmented and sectioned by the Gothic arches and domes which give it form. Its undulating surface is perforated with small holes the diameter of an eye, each housing a plug which rises up like a nipple. With no head and a brick/plaster skin a maximum of 20 centimetres thick, this architectural monster is bent and buttressed into position through a combination of experimental mechanical engineering and gravity.

July 20th 2016

In the summer of 2016, we spent three weeks in the Gothic Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis,1 located in the Northeastern region of Paris. The above text describes an attic space set between the concrete roof of the basilica’s domed ceiling and beneath the interior created by the basilica’s steep verdigris-coloured roof. Despite its vast size, this attic is inaccessible except to a few archaeologists, conservators, maintenance workers and administrators, who all maintain a unique long-term, if not life-long, working relationship with the building. We were given unrestricted access to the labyrinthine and often vertiginous non-public spaces of the basilica, which sit just inside, behind or outside the metre-thick walls. On the periphery of the action (religious, touristic and administrative) which takes place centre stage in the nave of the church, these spaces provide the backstage scaffolding, machinery and support for the astounding architectural pomp of the building, though can themselves be described as anything but mundane.

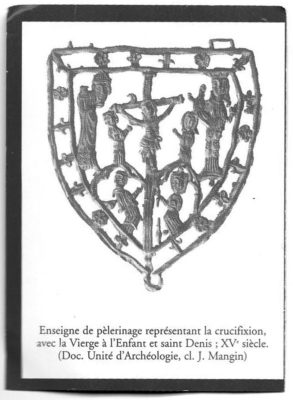

The basilica finds itself located on the external fringes of the Boulevard Périphérique – the orbital road which divides Paris from its suburbs – in the town of Saint-Denis, whose eponymous icon is a walking, talking, head-carrying cephalophore. A famous French martyr, St. Denis, was purportedly decapitated by the Romans as punishment for his Christianity, at the base of Montmartre in the 3rd century.2 He then proceeded to carry his head (or according to some accounts, part of his head), cradled in his arms, from his place of execution to the town which today bears his name. Perambulating along the route of the Seine (which now flows under the Boulevard Périphérique), St. Denis’ severed head preached a sermon until finally falling silent and dead at the location of the current basilica, thus founding the site of the subsequent medieval town and today’s Parisian satellite banlieue.

Up in the crawl space we imagine a glamour-death; one where our dead-weight starts off an unstoppable web of accelerating fissures spreading out across the decrepit domes, causing us to suddenly and without warning burst from the roof. Our prostrate bodies will fall sacrificially right on top of the altar, to be stared at and photographed by unfortunate tourists and worshippers. Matthieu says with a giggle ‘Don’t Jump!’, and we half-laugh along with him.

July 25th 2016

We originally came to Saint-Denis as part of a transdisciplinary project (NEARCH),3 bringing together artists and archaeologists. The project had, at intervals, also led us to Gothenburg, Nîmes and Maastricht on a series of site visits and updates. One aim of this article is to explore and unpick a small sample of the encounters we found in this network, through the motif of the crawl space: a space which is, on the one hand, located tangibly in the basilica’s attic, whilst on the other hand can also be conceptually located between the disciplines of art and archaeology.

By analogy, we also wish to extend the motif of the crawl space in two more directions. The first is in the severing cut made by St. Denis’ executioner which is, as far as decapitations go, a striking representation of the Cartesian split between body and mind by virtue of its violent instantaneity. As such, it can also be extended metaphorically to various social ruptures which occurred throughout Saint-Denis’ history – a direct result of political, economic and technological upheaval. The second explores the way in which this motif can be extrapolated through distinctions made between anomaly and waste, between identification and superfluity – or in more specific archaeological terms: between stratigraphy and the spoil heap. Crawl-Space, therefore, simultaneously assumes the position of an empirical motif and a methodological recess. As the space (the gap) and action (the cut) which separates the cephalophore’s head from body, it has become a guiding principle for our research and output. In characterising any site as a crawl space, we aim to show how method can be extracted from synchronous interactions with discrete players and co-producing partners, who are not directly yet in relation yet, nevertheless, overlap. For example, an empirically existent place as a motif (the attic space of the basilica), a recess that is the trans of transdisciplinary encounter (between art and archaeology) and the division that is the result of decapitation (St. Denis). Together, these notions of site have developed the nascent principle guiding the performative character of our research and its productions.4

Yesterday late afternoon Matthieu took us up to the belfry, accessible only through a series of locked doors and narrow passages that lead behind the pipes of the organ, corkscrewing up through the hollow columns that support the remaining South tower. The bell itself was absolutely enormous; at the end of its clacker was a ball as large as my head, and in a somewhat disembodied state we listened as a distant chime entered stage left, almost mocking the huge schlong clacker in an act of subordination. It became evident that the Mairie (or town hall) – the adjacent building in the main square – had substituted the basilica bell’s ear-splitting mechanical peels for a series of compressed pre-recordings, sent out by a loudspeaker attached to its facade like an old-school public address system. The basilica’s bell no longer marks time – a symbolic sound of civil order – the municipality does this now with an expedient prosthetic substitute. I suppose it’s a bit like Denis carrying his prosthetic voice in his hands…Later that day I wait dutifully in the square to record the 6 o’clock iteration, my eyes fixed on the speaker. A merry-go-round is pumping out acid colours, lights and music. I wait for quite a while, sound recorder in hand, but nothing happens. I press stop and make my way to Carrefour, slightly disappointed.

July 16th 2016

A crawl space as a physical entity is most commonly understood as an inaccessible area in architecture – usually due to human height restrictions – which might conveniently conceal wiring, plumbing or any other number of infra-architectural elements; it is the space between a false ceiling and the interior surface of a roof. Whilst the basilica’s attic has no human height restrictions, clocking around twelve metres at its highest point, any visitor is advised – after departing the centrally-located duckboards in order to crawl across its domed surface – to spread their weight as far as possible when negotiating the ten-metre-wide curved hillocks. Below their feet, which rest on twenty centimetres of medieval masonry, is a fifty-metre drop into the cavern of the basilica.

To be in the attic of the basilica was to occupy a liminal zone between worlds. In this forgotten space of trapped birds, we were always distantly aware of the historic town square below, the architectural structures whose identities and functions had become contorted by and intertwined with historical, economic and political events. The girls’ school Maison d’éducation de la Légion d’honneur connected to the South-side of the basilica through the old abbey, which was requisitioned by Napoleon for his new school in 1811. Then, to the West, is the Saint-Denis market, probably the largest and most ethnically diverse in the whole of Paris; and beyond that the Rue de la République, which, most recently in November 2015, achieved dubious media fame for being the location of a shoot-out between police and terrorists after the Bataclan attack. It leads directly from the basilica’s square to the Gare de Saint-Denis.

Nipples protrude at regular intervals, concentrated mostly along the seams of a series of convex and concave ribs, which are individually intersected by smooth, barrelled bellies. Look a bit closer and you can see that each nipple is topped with a circular wooden disc approximately 4 centimetres thick and 12 centimetres in diameter, attached from its centre by an umbilical chain a few feet long embedded into the original plaster dermis of its mother. The wooden disc is the perfect size to fit into the palm of a hand which, when it does, is graspable and removable, revealing the disc to be in actual fact a plug of mushroom-like proportions. Each plug conceals a hole (more of a puncture, really) and when the plug is removed a short jet of archaic black-dust erupts upwards in a short, warm exhaled gasp, followed by a few disorientated and stumbling spiders. After clearing away some of the debris with Ikea barbeque tongs, we use a camera lens to telephoto into the space below. We watch this on playback on the camera’s tiny monitor, transfixed by the experience of seeing something in detail that our naked eyes cannot see. The camera frames the content of each puncture: miniscule recumbent statues stare back at us; tiny tourists photograph each other and the shrunken architecture; a miniature wedding takes place. This grey attic we are in frames the warm afternoon glow of the basilica’s interior and there is something acutely comforting about inhabiting a building with such a prescribed set of functions in this objective way.

July 20th 2016

The Calender and the Dustbin

On the roof of the basilica’s North tower, in view of Olivier harvesting honey from his urban apiary, I photograph the mason’s markings that Matthieu is showing us. I see this as a good opportunity to capture the recording of the prosthetic town-hall bell – a good time and good proximity. In advance of 12 o’clock midday I press record and continue photographing. 12 o’clock passes and again the bell does not ring. I press stop to save the recorder’s batteries. About 10 minutes later the bastard bell rings.

July 17th 2016

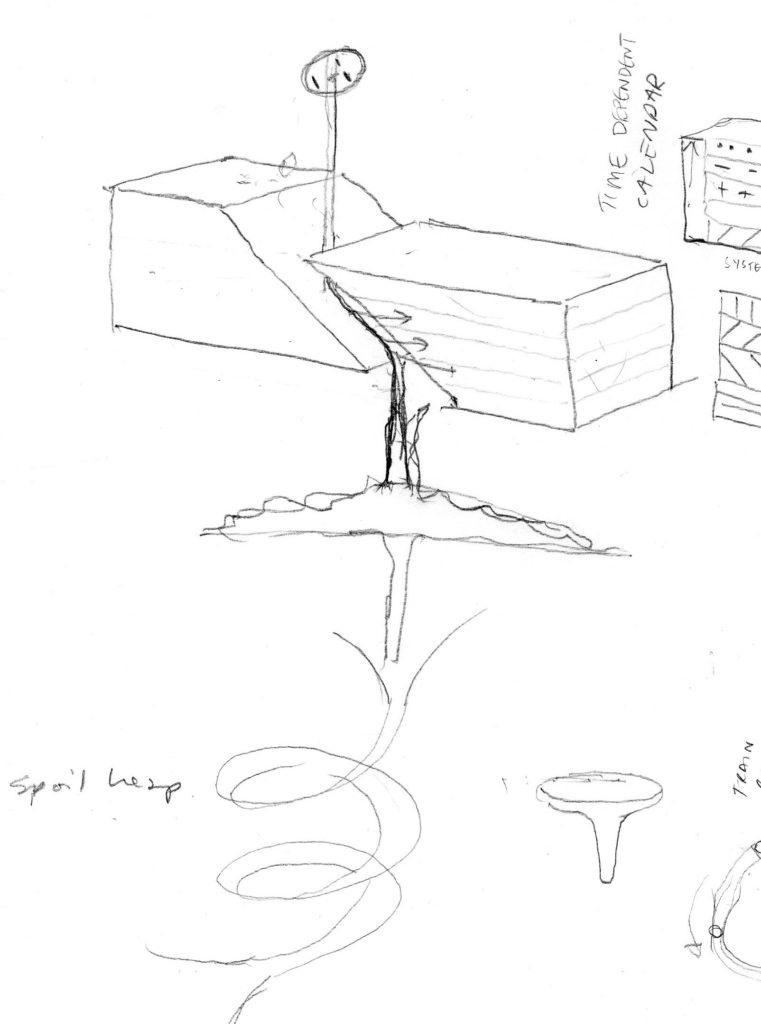

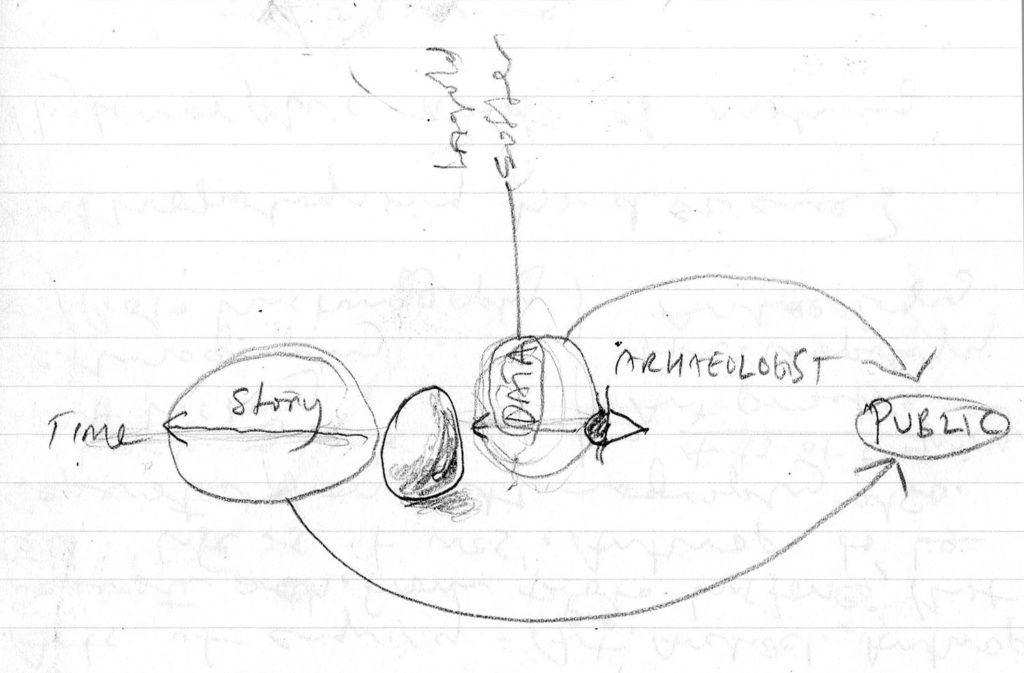

In archaeology, stratigraphy is the process of identifying strata within soil: to read matter, to date remains. During excavation, the stratigrapher identifies colourful and textural differences in the soil. From such differences, due to environmental and historical factors, and from the remains (often pottery) found within the strata, the stratigrapher hypothesises dates to the layers she identifies. Items of note, i.e. remains (in negative or positive form), are separated from items with little or no historical value. Items of note are then taken to specialist facilities and analysed, eventually finding their way to various storage depots. The latter – undesirables – are discarded and skipped. This is an activity of counter-production; spoil, waste, debris or residue is matter, which then assumes another role through reemployment in development and commercial industries, thereby re-entering existing socio-political and economic processes. This happens through the basic mathematic axiom of addition and subtraction; what gets dug out or pulled down must somehow get dug in or put inside a storage facility.

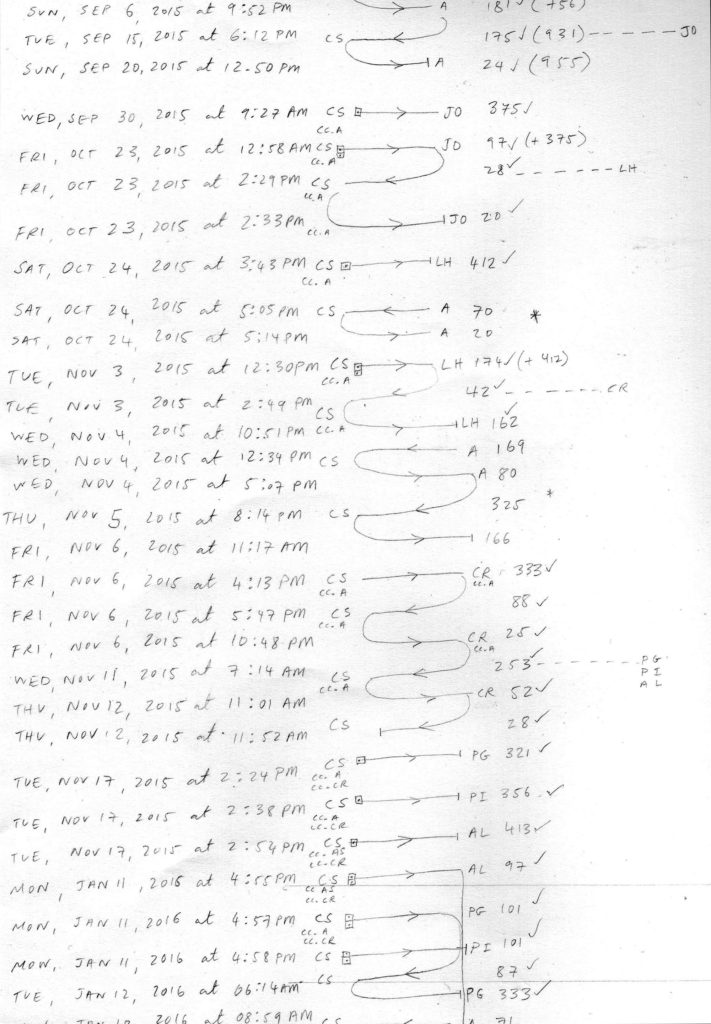

The itinerary of an email communication thread is a tracking device used to quantify word count expenditure and recompense. In this case, its function is to make clear that the conversation is one-sided.

This is particularly true for preventive archaeology, where industrial and commercial development creates contingent moments for archaeology to respond, albeit in an anticipatory and yet partial manner.5 As a result, it ties a vast amount of archaeology’s investigations to economic and social factors which are driven in large part by corporate profit, and in turn it shapes historical data. The motorway and high speed rail link excavations we encountered in Nîmes, undertaken by Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP),6 were the antithesis of the romantic ruin: megaprojects,7 irreversibly casting their forms into and across all types of natural and man-made landscape indiscriminately.

We arrive at Gare du Nord and are met by Valérie, a tourism intern from the local tourist office in Saint-Denis. She must be around 18 or 19 years old, with greasy hair and glasses. She is wearing a red t-shirt, short shorts, and trainers. She attempts to speak in English and we attempt to speak in French. We don’t really know what the hell is going on or who Valérie is or what we are doing with her. It transpires conversely that Valérie also doesn’t seem to know who we are or why we are there or what we are doing here being accompanied by her. She takes us on the train to Saint-Denis…Later, close by the basilica, we order food and sit in La Breton, gently sweating in 32-degree heat. Cow nose in aspic and melon with parma ham arrives. We have just been introduced to Antoine, the stratigrapher, who asks us directly and without preamble what we plan to do in Saint-Denis. We are by now familiar with this type of question from field researchers, administrators and pedagogues. We respond by gently explaining that we can’t speculate on output before research (I don’t think we know why we are here but, ironically, this is exactly the method of preventive archaeology that Antoine is engaged in – everything and anything is game). In our case, the gathering of data into information can only be done after the object of research has been fully turned inside out, like a pocket. But instead of being concerned with the contents of the pocket, we are more interested in the fluff which is left behind. Or perhaps more accurately we take the pocket including the fluff attached as the structure of the pocket: pocket plus fluff equals structure of pocket. Main course of roasted rabbit arrives.

July 6th 2015

Looking around the corner of art’s stratigraphic relation to archaeology is the spoil heap: waste produced and discarded from data production. All processes produce debitage – shrapnel from both ends. The transdisciplinary process is no different: a cow nose in aspic consumed at a Breton restaurant around the corner from the Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis, an email correspondence requesting access to spoil, a car parking ticket as the residue of visiting an underground car park previously excavated by INRAP, encountering an intern rather than an expert, funding proposals, authorisation labels and logs…these events and remainders are equally fundamental in constructing the transdisciplinary encounter, whether we choose to follow the trajectory of a failed email exchange or a spoil heap.

The large-scale excavation of Gamlestaden in Gothenburg, of the medieval settlement Nya Lödöse, started in 2013 and was still ongoing in the summer of 2016. The excavation proceeds at intervals (weather allowing) through the ex-industrial riverside suburb, contrapuntally rotating its jigsaw pieces in line with the timetable set by construction company Skanska, which is required by law to pay for the dig.8 When we visited the site in March 2015, the second series of excavations were in progress. The first had already extracted the entire contents of a medieval graveyard, been filled in and was covered with grass and tarmac on which we came to stand, in preparation for the new bus depot and a future crop of residential flats. Whilst there, we caught wind of a rumour circulating amongst the students and faculty members from Akademin Valand (incorporating the School of Fine Art) – who had been using the recent excavations as a pedagogic opportunity for participatory art projects – that one of the islands of a Gothenburg archipelago was apparently being used as a deposit for waste from the Gamlestaden dig. Baited by the compelling notion of what this might mean for archaeological spoil on an industrial scale, we were curious to try to trace the parallel movement of this spoil alongside the administrative and bureaucratic procedures that were guiding its passage via skips, heaps and holes.

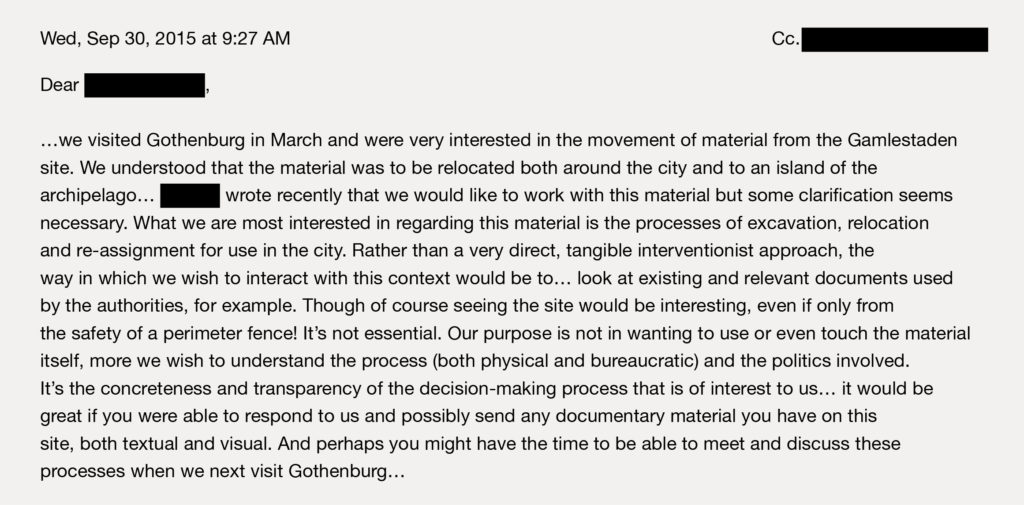

After being put in contact with council representatives and county officials, who put us in touch with the archaeological contractors, who put us in touch with the property developers, who then put us in touch with the construction site contractors, we established – during long periods of silence prompting second and third email reminders, eventually leading us back to an unceremonious re-dumping at our initial point of contact on the site – that passing the buck on our question was likely due to ambiguities in Swedish law concerning the use of historical material (defined as material pre-1850). Nobody wanted to enter the ambiguity or complexity (of which we were not aware) of the legal question at hand.9

Essentially, it was also true that nobody had the time; many of these players were employees attached to public bodies, or else self-employed specialists working for commercial businesses with only limited and largely self-electing responsibilities to communal questions. It was not surprising that nobody wanted our rather prosaic and inevitably amateur questions to arrest them in their inbox. However, this is stated with the acknowledgement that an information vacuum develops as a result of a switch in guardianship to industrial players and away from the curiosity and generosity of academic players, all of whom are completely aware of the dangers of private control over communal heritage, and yet impotent in the face of them.

A Communication Officer exists at the boundaries of companies, groups and communities; even its own.

Our experience in Gothenburg – the wild-spoil-heap-chase and the circularity of email forwarding that only returned us back to our initial point of departure – revealed the extent to which large scale urban archaeological initiatives are fundamentally tied to property developers, and in turn to contractors. Tracing a thread of the archaeological process led to potential participants having absolutely no interest in the collaborative attempt, yet without their input, we realised, all we might be left with were familiar tropes and motifs of an art/archaeology paradigm.

The network was full of players at the borders of archaeology: the privately employed conservator going from temporary contract to temporary contract, the builder chosen for his uniquely sensitive touch for a hydraulic excavator digger; the PhD student washing mud outside through a sieve all day in minus two degrees. Yet despite this, it became clear that it was this condition of peripherality which called many of the shots. Each player gave birth to another network of players, constellating, compromising and fracturing any possibility of a united whole. When this metastasised network came into contact with questions of legal uncertainty and responsibility, it revealed a Catch-22 situation. In order to progress, the non-specialist must ask the specialist the specific question in order to receive the specific answer. It appeared that archaeology was only figurable by delimiting its sprawling network to interested parties who were, unsurprisingly, already invested in its narratives and frequently isolated within their specialisms, unless, that is, one took this frustrated issue as paradigmatic.

My face is tired from all this smiling we have to do. We walk from lab to lab, herded by Anneli, who introduces us to an impressive roll call of science professionals. There is a constant underlying pressure to ask question after question, never knowing if it’s the right one. And you do this with the knowledge that these people owe you nothing and that you only have one chance to get it right. Every time. Everyone we meet has that look that I must get when I’m cornered by a wine-soaked, slurring family friend in a panama hat at an anniversary party (not my own) and they want to talk about ‘art’. I expect the stupid questions. So, it follows that these archaeologists must do so too. And we do not disappoint. Because, I have started to realise, if you don’t end up getting an answer to a stupid question, then you know you’ve hit on something.

March 20th 2015

Preventive archaeology is itself a site that does not fit into the received tropes and motifs that mark the relation of art and archaeology. The fact that it is often also called ‘rescue’ archaeology explicates the tension between a scientific discipline that ‘saves’ only by virtue of the ‘liberation’ afforded to it by the development and construction industries. As in many complex relationships, the two must – as a matter, of course – both resent yet need each other in order to exist and thrive. In our extended experience of the Gamlestaden encounter, formal and historical precedents of art and archaeology’s own relationship (aesthetic and communicative) could not be found. Instead, a Gordian knot of politics, science, history, economics and bureaucracy framed the site of an emphatically unforthcoming encounter. This frame articulates the encounter as a seemingly shitty spoil heap of uncommunicative waste. However, we came to understand that this uncommunicative process is in fact a preclusion to a valuable spoil heap of archaeological practice, a mine of artefactual riches, if one concentrates hard enough on the peripheral.

I’m back at the town-hall to meet my nemesis. I look at my phone as it approaches 6 o’clock. At 3 minutes to the hour and in case my phone is inaccurate, I press ‘record’ on the mic. The phone counts 1, 2, 5, 8, 11, 15 minutes past the hour. No bell. I press ‘stop’ and now, total in my defeat, I walk over to Le Khedive for a litre of beer. 20 minutes later, sitting in front of the recently restored West facade of the basilica which now appears glaringly naked without its thick, black crust of industrial-grade pollution, I look at the long arm of the clock – shaped like a meandering snake – as it points to 35 minutes past the hour, when suddenly the recorded bell rings out. I don’t care anymore. I have my beer.

July 18th 2016

Decapitations, Deliveries and Depots

The art/archaeology axis has a history marked by certain modes of looking and reception; distributions of cognition and communication mark their relation and produce a cross-disciplinary history that can itself be considered stratigraphic. The transdisciplinary field we find ourselves in today is immediately predisposed to having contrary implications for the canonical and chronological – intervention, derailment, appropriation and subversion are all transdisciplinary tactics which promote new perspectival shifts and historical reassessments. Together, they pose the insistent and oppositional question of indeed how not to reproduce the familiar tropes and modes of looking, form and production, which characterise a historical (and frequently romantic) relation between art and archaeology.

For artistic practice, to reduce (or extend) the concept of stratigraphic markings as a range of familiar archaeological metaphors arising from method makes the mistake of assuming genealogical – and in doing so, continuous heritage – narratives. Although this may provide a helpful streamlining of the past into an accessible data gateway, there is also the risk that, through reiterating what has become a series of conventional modes of relation, challenges to the established narratives and contingencies encountered are displaced or ignored.

The following is an incomplete list drawing attention to a broad range of some of these potential ‘conventional modes’, which present themselves in some cases as inevitable primary response mechanisms. This is perhaps because of the self-validatory nature of any given discipline where existing methodologies are offered up for adoption to the transdisciplinarian as she departs the safety of a discrete field – whether they be aesthetic, communicative, political or epistemic – as convenient guides or channels to occupy.

The first is the (1) political-aesthetics of temporal-romanticism, an admittedly catch-all (but not, perhaps, catchy) term, although one which, nevertheless, extends in many directions. At an extreme, this approach operates under a (pseudo-astrological) sign, in which a full circle allows an archaeological past to couple with a future, often appearing in popular entertainment’s narratives of science fiction as an erudite statement of political agency.10 This cyclical redundancy of time extends to the entropic in the work of artist Robert Smithson, where the phrase ‘ruins in reverse’ has often been quoted in order to explicate entropy as a process of construction as well as confusion.11 For Smithson, the ruin only becomes termed as such dependent on the view from which one might be looking at it, more pointedly in finding a use-value. Despite the epochal horizon that Smithson’s views occupied at the time, the ‘political-aesthetics of temporal-romanticism’ is an approach seeking political agency, yet in being intrinsically non-empirical,12 results in an unavoidably hallucinatory and therefore ultimately romantic encounter.

The second ‘conventional mode’ is equally, if not more, romanticist: (2) nostalgist mimicries of surface/layer processes, the most common trope, which can be found in the consideration of the surface of painting as a support for excavatory processes or the valorisation of ‘the fragment’, alluding to an indexical passing of time. This also finds resonance and contemporary relevancy with some strands of media archaeology, where an exploration into technical vestiges often results in a mediatic escapology into technological patination.13 This imitative slant can furthermore be extended to multiple (3) metaphors of the spade and the dig, which have been recently utilised by artists and curators alike as a broad umbrella under which to fund largescale projects, public artworks and exhibitions.14

The fourth ‘mode’ adopts archaeology as a taxonomical tool to challenge dominant cultural heritage narratives, where (4) reclassifying the cultural and or social status of objects is employed to attain a cultural equivalency between the art object and the social artefact. This approach, however, in blurring the political and historical categories of art and social artefact, often neglects (in its conflation of the cultural with the social) to take into account the operational chains that produced that differentiation to begin with. In this ‘mode’ we may applaud a challenge to dominant hierarchies. However still in fixing its gaze upon what it considers to be sites of cultural relevancy, it might inadvertently obscure and erase its own social production, thereby perpetuating the very possibility of value and status distinctions. If we reverse this ‘mode’ – for example instances where archaeology uses art as a mirror to look at its own reflection – this is most apparent in (5) re-imagining field work as land art or performance art.15

The penultimate ‘mode’ in this list is situated in the arena of identity politics, where archaeology and art become (6) co-contributors to a narrative of origins. That is, they become active producers in a performance of heritage and therefore constructors of national identity narratives.16 To approach this from a critical standpoint, the notion of the past as something which only speaks to a specific set of people attached to a place in time is an obstacle when it comes to communicating a heritage that can be shared, accessed and valued by anyone from anywhere.

And finally, more generally, a strategic mode that employs any of the tactics above (7) the employment of art as a communicative tool, deployed under the guise of community outreach/knowledge transfer, seeking a wider public who does not find archaeology an engaging enough locutor without these communicative tactics.17

If we view the above as a set of potential ‘modes of relation’ or channels, which historically and bureaucratically, but also politically, epistemically and/or aesthetically precede the transdisciplinary encounter between art and archaeology, this raises the question of how to side-step these primary response mechanisms. An urgency arises, that in situations where art is asked to plug a gap in a predetermination of its role, the real challenge becomes in fact how to articulate an encounter as it is found – warts and all. And an encounter which is vulnerable to, above all, contingency. In this situation, the transdisciplinary encounter itself becomes something which can be addressed and reproduced as an outcome, a net which can be thrown out both spatially and temporally, collecting the remainders of a metastasised milieu. For example, the sprawling deferral of email communications that we experienced in Gothenburg.

In this way, the repetition and continuation of what marks the transdisciplinary past as a past becomes a foil in which neither art nor archaeology risk becoming marked by each other in their encounter. Instead of continuity, stratigraphic topography is a mark, a cut, line or division; it differentiates rather than accumulates. The task, when proposed stratigraphically, is to produce something non-identifiable as collaboration between art and archaeology that is nonetheless a result of their encounter. Crawl-Space as site attempts to find the thickness of this cut or line in the para-data – for example, a cow nose in aspic as the debitage of its social encounter – in order to mark that encounter.18

In the carapace-filled basement of the ‘temporary’ museum storage facility, two rows of Volvo cars – elaborate customisations from 1927 to sometime around the 1960’s – perform, model by model, an excerpt of their evolution. The director Linnea says, ‘We have no space left, none at all…and now they want us to take 200 corpses!? But of course, we should and we must – in the name of professional ethics, not to mention morally – people get very upset about this kind of thing you know… ah yes, technology is developing at such a pace everything we do now will be considered completely stupid in about 100 years…’

March 23rd, 2015

The headless figure of St. Denis kept returning to haunt us. As a compelling figure of meted violence and fragmentation, we saw evidence of his severing echoed and repeated everywhere, only in new updated versions: the Boulevard Périphérique which carves away the banlieue of Saint-Denis from the capital, the town hall’s tape recorder divorcing the bell’s sonority from the basilica (a heckling imposition on the town square), the digger or cleaner (dustpan and brush) dividing the spoil from the stratigraphy, particles of blasted sand forcing their way between pollution and renewal, Franciade, the name French Republicans gave to Saint-Denis between 1793 and 1803 interrupting the continuity of municipal identity. During our site visits, the cephalophore became a kind of talisman for the structured divisions we encountered and increasingly looked for, a kind of prophetic fortune-teller of carvings and subdivisions. Imagined as a type of ventriloquist’s doll, he takes on the qualities and demeanour of a satiated zombie.19 Death and his message, as such, is delayed – in any case the voice box has been cut straight through and rearranged. The message becomes infinite and self-perpetuating.20

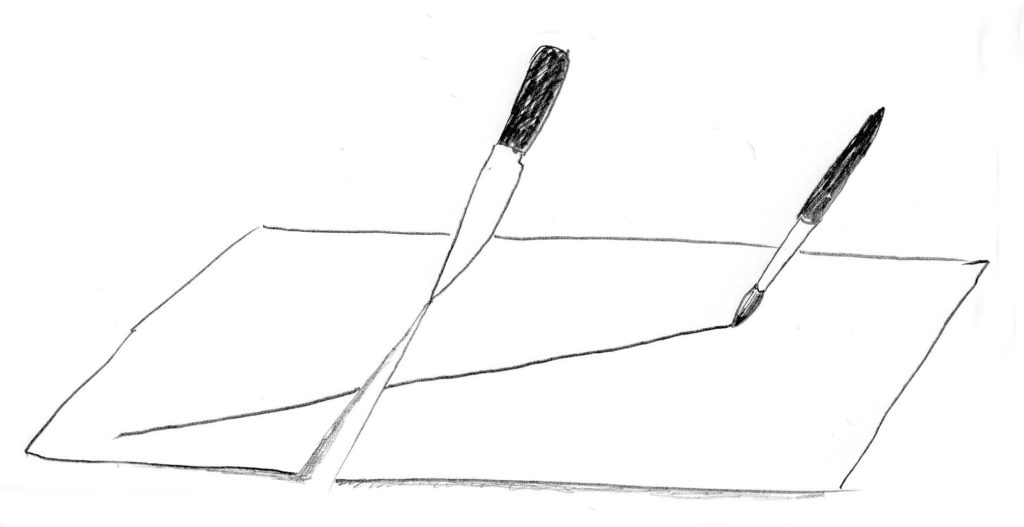

The cutting tool that severs St. Denis’ head is a distributor. And in that act of distribution, a crawl space emerges. Crawling into the space of the cut is not like magnifying a line or plotting the distance between upper and lower cross-sections of a severed neck, but is instead the gloop of the cut’s remainders – some of the matter lost to blade and of some of the blade lost to matter – a microparticulate exchange of blood for metal on the upper and lower cross-sections of St. Denis’ neck. Our crawling space is only as good as the thickness of this exchange, of identifying remainders from the process of distribution.

We got on the bikes again today and cycled up to where Viale del Galoppatoio meets Via Veneto on the outskirts of the Borghese Gardens. This time we bring the basilica’s mushroom plug with us in preparation. Its shape is coincidentally an almost exact double-mirror of the architectural design of Luigi Moretti’s underground car park;21 the columns supporting each level assume both a positive cast of the stem of the plug, whilst the gridded, shallow, anamorphic domes inset into the ceiling at each level look like they have been made by a gigantic hand pressing a gigantic plug upwards into the concrete at regular intervals. In this space, next to golden-monogrammed golf buggies; we dangle, pose and shoot the plug above a series of concrete reinforced holes made by historic scaffolding – where it fits like a standard hand into a standard glove. Like muscle memory, we also repeat the same physical movements and choreography as we did in the attic of the basilica, re-performing those very same actions, now seamlessly.

August 11th 2016

Between Moretti’s storage depot for the cloth-covered Ferraris and the basilica’s attic space, an infrathin crawl space emerges. Marcel Duchamp’s infrathin difference between two events; such as the difference between two mass-produced objects cast from the same mold, or separating the smell of cigarette smoke from the smell of the mouth exhaling it, is also perhaps extendable to the difference between two choreographic repetitions;22 repetitions which take place across two geographically distant and empirically antithetical sites. Even with the acknowledgment that both the car park and the attic share a morphological and formal detail of design, it is in fact the learnt choreography which translates and relocates their spatial, temporal difference. This choreography osmotically absorbs and then exudes the encounter of body to site and site to body – two habituated performances where muscle memory and motor response provide the transit for a crawl space to emerge.

The pantomime dachshund is the sister of the pantomime horse. However, in order to operate, the pantomime dachshund requires three people instead of two; one at its head, one at its rear and, most integrally, one which bridges the mid-point of the dachshund’s belly.

We sit in a public garden in front of the Roman amphitheatre in Nîmes, watching the sun dip behind stacked arches. Earlier in the day, Pierre-Simon had said, ‘the tools shape the method’. He said these words as we looked towards the incline of a huge excavation overlooked by a mountainous landfill site, where birds circled and dive- bombed behind articulated dump trucks shunting and levelling layers of rubbish. Beneath the landfill, archaeologists in full protective high-vis suits with respirators worked, using vehicles and machinery not dissimilar to those on the rotting escarpment above them.

April 3rd 2016

Archaeological warehouses burst at their seams with bulky material data in storage facilities like a film set’s prop store. At the same time as digital archival techniques struggle to respond to the almost incongruous question of their own simultaneously degrading media artefactual status. Racing against technological time? Even oyster shells submitted to oxygen isotope analysis contribute to a gridded and inventoried space that is held together by a notion of ‘storage’. Producing historical time? If archaeology and its institutes are increasingly involved as collaborators who coalesce to produce historical time on an increasingly industrial and technological scale, then what are the ramifications for desiring a complete picture of the past? The grid that arranges the data enlarges, the mesh becomes finer and more systematic, the storage warehouse grows larger – filling in the blanks? Perhaps these are not historical blanks of time, but are in fact the technical blanks that produce archaeological method.

In this way, archaeology appears voraciously interdisciplinary – any complete picture is challenged by an appetite to incorporate external disciplinary methods. Scientific, technical methods (geological, biological, chemical) enlist cultural methods (art) to produce relevant narratives from a sprawling data set, but ultimately struggling to connect the two. Crawl-Space, in proposing its own site, forms it from a compendium of the slight: bureaucratic and communicative chambers of the exchange between art and archaeology, superfluities existing on the peripheries of that encounter which find analogy with its hagiographic narratives, re-experiencing its backstage architecture through the peripatetic translation of muscle-memory, and in making waste a position from which to reflexively produce method. This encounter does not come from taking a stance in existing fields, but arrives as their surplus. In this surplus, both encountered and extended – a heap of cow nose, a digital waste bin of email messages a bloodied sword – pre-existent imaginaries may loosen and any player might have an opportunity to reconfigure their indigenous understandings.

Pierre-Simon arrives at the INRAP Méditerranée offices in Nîmes in a whirlwind of hair, tight jeans and éclairs. Holding an éclair sideways in front of Carolyn’s computer monitor, he gesticulates enthusiastically whilst describing the arduous task of 2 years of excavating and clearing land for the infrastructural development of the high-speed rail link connecting Nîmes to Montpellier, following the route of the ancient Roman road via Domitia. As the only route connecting Southern Spain to Northern Europe and Scandinavia, a general increase in both commuters and goods both coming and going, had eventually strangulated the route with excess traffic congestion. Going deeper into the political intricacies – the path beaten by the rail link can displace people who have lived there for 50-plus years, but not environmentally-protected plants23 – some cream remains at the corner of his mouth from his delivery of the éclair.

April 5th 2016

1. The basilica is widely thought to be the first manifestation of the Gothic architectural style in Europe, taken up as the template for subsequent Gothic cathedrals, but increasingly put on steroids – as demonstrated through the spectacular bombast of buildings such as Chartres, Reims and Orléans to name but a few. The basilica largely derives its current form from the 12th century, when it underwent massive renovation and expansion. The man responsible for this was Abbot Suger – an ambitious and charismatic monk whose religious zeal was only matched by his talent for economic prosperity, self pro motion and predilection for all things gold. See Suger, Erwin Panofsky and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel (1979) for a comprehensive translation of Suger’s writings on the 12th century renovation works of the basilica. Suger, Erwin Panofsky, and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel, Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979).

2. Montmartre derives its name from St. Denis’ matrydom, meaning ‘mountain of the martyr’. Alongside St. Denis, St. Rusticus and St. Eluthère were also martyred and subsequently commemorated in the basilica – three golden reliquary caskets sit in pyramid formation at the back of the ambulatory, one for each saint.

3. NEARCH is a European Commission-funded project bringing together archaeologists and artists. The Crawl-Space project engages with four research institutes: Archaeology Department of Göteborgs Universitet; Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP), France; Unité Archéologique de la Ville de Saint-Denis (UASD); and Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht.

4. The term performative is used to direct attention to the descriptive forms employed in this article – diary entries and email communications – which are, on the one hand, forms of recount and document, but are also strategic devices that write contingent factors and superfluous information into the project’s outcomes. These descriptive forms operate with a double-ontology: both as a form of telling and reporting common to many research accounts, but also as literary form producing its own temporal stratigraphy and debitage of process.

5. According to the archaeologist Jean-Yves Breuil (INRAP Méditerranée), the birth of preventive archaeology in France came about in response to a range of high-profile scandals involving post-war commercial construction projects that had failed to properly assess or make provisions for the cultural heritage they might (and indeed did) subsequently unearth in the process of construction. For example, when the square in front of Notre Dame Cathedral was dug up for an underground car park in 1965, it was perhaps unsurprising that it revealed a rich cornucopia of ancient remains. In 1983, a similar thing happened during the underground extension of the Louvre under the aegis of Francois Mitterrand (See Bernstein, 1984). These were just two of many such cases where a conflict of interests was highlighted between government/commercial entities and archaeology in France, leading to a dramatic change in the attitude of the general population towards its local cultural heritage, which had previously, along with archaeology itself, been focused on post-colonial territories. As a consequence, the Valletta Treaty was passed in 1992, for the first time ensuring proper legal protection for archaeological heritage in Europe. As Breuil says, in this sense ‘preventive’ literally means ‘to anticipate, to plan, to defer…the heart of the law is not to excavate, but to preserve’. Richard Bernstein, ‘Paris’s Past Unearthed in Digs at Louvre,’ The New York Times, Dec 4, 1984, accessed April 2, 2017, at http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/04/science/paris-s-past-unearthed-in-digs-at-louvre.html.

6. INRAP (previously, Association Française d’Archéologie Nationale) is a state-run organisation in France numbering over two thousand archaeologists. All archaeological surveys must go through INRAP before the sites are put into tender for excavation with private businesses and university departments.

7. A megaproject is one which, as its name suggests, is humongous both in scale and expense, with wide-reaching (often irreversible) environmental, political and social impacts.

8. Following on from the Valleta Treaty, the ‘polluter pays principle’ (2001) is a legal form of financial compensation operating in most EU countries in which a developer or industrialist is responsible for potential damage to the environment, not the taxpayer or government. The principle enshrines the costs of waste into the costs of production. In Sweden, the location of Gamlestaden legally operates under the term Extended Producer Responsibility (originally introduced by Thomas Lindhqvist in 1990).

9. In contrast to French archaeological heritage laws, the Swedish system has been in place for an additional century or more.

10. Most popularly, the final scene of 1968’s Planet of the Apes famously depicts Taylor (played by Charlton Heston), discovering a beached Statue of Liberty, and cursing the political/economic perpetrators of its fate; in the same year, the opening scene to 2001: A Space Odyssey depicts apes encountering a cuboid monolith. Both scenes are concerned to present an archaeological time caught between past and future. See: Franklin J. Schaffner, Planet of The Apes (Twentieth Century Fox, 1968); Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968).

11. Robert Smithson, ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic,’ in Robert Smithson: Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 72.

12. ‘The future is an empirical field that does not exist’ – we know that the future will unavoidably arrive, but not what that future will be. Cornelius Holtorf and Anders Högberg, ‘Contemporary Heritage and the Future,’ in The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research, ed. Emma Waterton and Steve Watson (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 509.

13. How the patina of the media might enter the message is approached interestingly by Håkan Karlsson. Håkan Karlsson, ‘Why Is There Material Culture Rather than Nothing? Heideggerian Thoughts and Archaeology,’ Global Archaeological Theory (NY: Springer, 2005), 29–42. The matter is more generally approached through the aestheticisations of glitch culture.

14. See Dieter Roelstraete’s 2009 e-flux article ‘The Way of the Shovel: On the Archaeological Imaginary in Art’, which provided the basis for his 2013 book of the same name. See also the exhibition at Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Nov 9, 2013 – March 9, 2014. Dieter Roelstraete, ‘The Way of the Shovel: On the Archeological Imaginary in Art,’ e-flux (2009). Accessed April 2, 2017, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/04/68582/the-way-of-the-shovel-on-the-archeological-imaginary-in-art/.

15. Michael Shanks is one of many who have drawn parallels between archaeology and land art, however he provocatively compares the archaeological process to a striptease. It could be speculated that Shanks might also retrospectively consider Mark Dion’s Tate Thames Dig (Tate Modern, 1999) as a drag striptease performance of process archaeology. Michael Shanks, Experiencing the Past: On the Character of Archaeology (London: Routledge, 1991), 68–9 and 141–3.

16. See Christopher Smith’s discussion of Kitty Hauser’s study of O.G.S Crawford. Here, Smith discusses at once Hauser’s study of the birth of aerial photography in the military industrial complex, its subsequent adoption by archaeology, and the integration of complex national identity narratives in the work of John Piper, Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland in the period preceding and after the Second World War. Generally, Smith’s article outlines many of the historic relationships found between art and archaeology over the last 150 years. See: Christopher Smith, ‘Beyond Metaphor: Archaeology as a Social and Artistic Practice,’ Journal of Visual Art Practice 15:2–3 (2016): 270–85; Kitty Hauser, Shadow Sites Photography, Archaeology, and the British Landscape 1927–1955 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

17. NEARCH, itself an awkward acronym for ‘New Scenarios for a Community Involved Archaeology’, is often, in its enormous heterogeneity, torn between the desire for collaboration and communication, in addition to a desire for criticality.

18. The art historian and cultural theorist David Joselit introduces his 2009 essay, ‘Painting Beside Itself’ with a quote from the artist Martin Kippenberger: ‘Simply to hang a painting on the wall and say that it’s art is dreadful. The whole network is important! Even the spaghettini…When you say art, then everything possible belongs to it. In a gallery that is also the floor, the architecture, the colour of the walls’. For us equally, the entire network of trans-disciplinary encounters between art and archaeology is important. That includes: emails, introductions to gatekeepers, interns, parking tickets, property developers and high speed rail barriers, flies trapped in light fixtures and beheaded Christians. See: David Joselit, ‘Painting Beside Itself,’ October 115 (2009): 125.

19. For a post-Marxist interpretation of the iconography of the zombie in contemporary culture see: Lars Bang Larsen, ‘Zombies of Immaterial Labor: The Modern Monster and the Death of Death,’ e-flux (2010), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/15/61295/zombies-of-immaterial-labor-the-modern-monster-and-the-death-of-death/. In this context, St. Denis is the medieval precursor to the fixation on the Gothic which emerges in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. The word ‘satiated’ is used here to denote St. Denis’ paradoxical status; what Nicola Masciandaro terms ‘the double presence that precedes his head bearing body’. See: Nicola Masciandaro, ‘Non Potest Hoc Corpus Decollari: Beheading and the Impossible,’ in Heads Will Roll: Decapitation in Medieval and Early Modern Imagination, ed. Larissa Tracy and Jeff Massey (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 34.

20. In serial extension of this ventriloquised displacement, the medieval period sees St. Denis wrongly attributed authorship of the theological texts of Dionysus the Aeropagite, only for these to be later reappraised as the works of a different individual now referred to as Pseudo-Dionysus, the Aeropagite. False attribution and pseudonyms extend this Dionysian chain of broken links.

21. Luigi Moretti (1907–73) was an Italian architect noted for combining innovation and tradition. He is most famous for designing the Watergate complex in Washington DC. Between 1965 and 1972, Moretti’s design for a car park beneath the Borghese Gardens was completed. In 1973–4, after Moretti’s death, the site hosted the international art exhibition Contemporanea, including works by Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis and Mario Merz, alongside music, cinema, design and architecture.

22. Marcel Duchamp, Notes, trans. Paul Matisse (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1983), notes 1–46.

23. In a report released by the construction company Bouygues, the presence of a rare hybrid plant called Lythrum thesioides and a species of bird called the Little Bustard affected major changes to the construction works: ‘Particular care is being given to the Lythrum thesioides during the bypass project. This flowering plant was first discovered during the ecological inventory procedures carried out by RFF in July 2010 [Réseau Ferré de France was a French company which owned and maintained the French national railway network from 1997–2014]. It is only the second known occurrence of the plant in the world. Lythrum thesioides is therefore extremely rare and protected by both French law and the Bern Convention. Given the importance of this discovery, RFF has been conferring with government departments and environmental protection agencies over the best technical solutions to prevent the Nîmes and Montpellier bypass from impacting negatively on the plant’s natural habitat.’ See: Bouygues Construction, ‘Nîmes and Montpellier bypass: Réseau Ferré de France signs public-private partnership contract with Oc’Via for the construction of France’s first mixed freight / passenger high speed line,’ 2012.

https://www.bouygues-construction.com/sites/default/files/dp_signature_cnm_28.06.12_eng.pdf.