Movement, Intuition and the Validity of Literary Translation

Clive Scott

To cite this contribution:

Clive, Scott. ‘Movement, Intuition and the Validity of Literary Translation.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 12 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/movement-intuition-validity-literary-translation/.

This article pursues the argument that literary translation, in the version envisaged here, provides a way out of a linguistic quandary, and can re-establish the existential values of language. Every use of language, we might suppose, involves a double loss: (i) every term becomes, willy-nilly, a class term, subject to abstraction and conceptualisation, in the interests of easy transferability;1 one might argue that translation has a natural tendency to occupy this ‘average’ ground, easing the way to swift and confident comprehension; (ii) nobody’s understanding and use of a term corresponds exactly with anyone else’s; if translation accepted the full implications of this proposition, what kind of strategy would it envisage? So, this pair of statements confronts us with a contradiction: words become class terms in the interests of stability, in order that abstractions like ‘integrity’, ‘validity’, ‘joy’ carry their true moral weight, and in order that fine distinctions can be made, between ‘vice’ and ‘evil’, for instance, or between ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘reliability’. Yet, in becoming class terms, they lose that particularity which gives them experiential value and which might guarantee a semantic immediacy. How we make contact, through language, with the experiential as against the conceptual, how we resist the constant recasting of the experiential as the conceptual, remain nagging, unsolved challenges to institutional responses to text. It suggests that we should shift the emphasis from research-based practice – which converts experimental data into a body of knowledge and a methodology – to practice-based research – which pursues research as a mode of experiential becoming. It suggests, too, that we should find ways of making Bergsonian intuition a more essential part of critical attitudes, although we would need to revise Bergson’s views on both language and translation. More fundamentally, it encourages us to distrust validity as a critical criterion.

My own translational ‘solution’ to this predicament is to move the translational objective away from text towards the readerly experience of text, towards the activities of consciousness and perception in the reader, and this involves my shifting allegiance from a monoglot reader (a reader who cannot read the source text) to a polyglot reader (a reader who can read the source text), a shift that bilingual editions themselves encourage. Translation for the monoglot reader is a question of (invisible) transfer and equivalence, while for the polyglot reader, it is about relationship, variation, creative transformation. I do not wish to do away with translation as a service to those not familiar with the language of the source text; but I do want to suggest that it militates against the discovery and exercise of experiential contingencies in language, and I do want to lay alongside that version of translation another, one which does not derive a ‘validity’ from fidelity to the source text, and in particular to the meaning of the source text, or from its use of methods, or theory, accredited by the profession/ discipline, that is to say, one which applies to the act of translation procedures already tried and tested. I am in pursuit of a translation which explores the source text’s invisible, its virtualities and unrealised possibilities, as part of a reading process which naturally re-configures the text to maximize its experiential fruitfulness for the reader.

What is the reading experience? I want to pick out two aspects, while recognizing that there are many others. But the two I select are peculiarly significant for translation. The first is that reading is a form of self-coordination, in which text is the instrument whereby we regain our capacity for perceptual/sensory cross-wiring – I mean the capacity to relate, to integrate, various aspects of our consciousness and feeling, various propensities, various behavioural characteristics. Reading is an inter-sensory complicity in the text which will not take place if we surrender to interpretation. Translation is like an improvisation of ourselves through a given text, and thus an improvisation of that text. When we talk about reading as a process of self-coordination, we also mean that we are revealed to ourselves. Reading invites us to return to ourselves, to our entirety, without that, however, constituting a completeness; it is this incompleteness which necessitates a writing; this incompleteness is an inevitable concomitant of our being in movement, in duration, in a state of continuous becoming.

Second, reading is a dynamic experience. Speech, however little phonated, introduces the paralinguistic and prosodic into the linguistic, that is, all those durational elements of voice – tone, intonation, tempo, loudness, pausing – which the printed text may from time to time imply, but gives no explicit indication of. We respond to text by vocalising it, by performing it, by tracing a body in it, rhythm in its paralinguistic or vocal multi-dimensionality. Just as choreography turns the movement of music into one’s own dance, into the participation of one’s own body, so translation turns source text (reading) into target text (writing) by making reading a lived and living movement, which demands to be expressed, to be embodied, to initiate an activity that further develops. In short, we turn the movement of the reading eye that activates a text into a mobile text which activates the readerly body. Expressing it another way, we might say: a textual environment, set in dynamic motion by the act of reading, generates an action within us which we participate in, by ourselves acting (writing, drawing, doodling), an acting which takes us in new directions.

This is a translational practice which espouses Bergsonian vitalism in several senses. Translation is not seen as a succession of finished states, of detached texts, but as an incessant variation which passes through different versions in the unfolding of its duration. These versions make no sense other than as a forward-rolling, expanding, interactive body of inputs: ‘Duration is the continuous progress of the past which eats into the future and swells as it advances’.2 The source text is not so much a completed event that needs to be retrieved, returned to; it is, in its very forward momentum, a metamorphic entity which is never the same, as self-differentiating as it is self-conserving.3 But let us be quite clear. I am not speaking here of that ‘passive’ change that is built into the very process of historicity: a new moment inevitably begets a new reader, a new reading, a new interpretation. I am speaking, rather, of the responsibility translation takes upon itself, whether it is intralingual or interlingual, continually to explore, across language(s), what the source text contains of the virtual, the invisible, the unfulfilled, which are not products of historicity, but elements in its own becoming, its own duration. Duration is as irreversible as it is unpredictable; a work has no destiny to fulfil other than to be in the middle of organic mutation, even if, in retrospect, it looks as if it has moved along a predictable path; that is to say that translation projects the source text into the future as an unforeseen possibility, and without any knowledge of its own consequences.

That is also to say that duration is significant by virtue of being inhabited time, of being the very motions of experience and consciousness, not by what detaches itself from it, as product; the problem is that such a view leaves us deprived of the quantifiable and demonstrable. Can we bear to be deprived of the evaluative and judgemental capacity, the procedures of the intelligence, the instruments of validation, do we know how to cope with a non-immobilized subject of scrutiny, a subject which demands participation and practice instead?

The intelligence, in Bergson’s eyes, puts us outside experience, and because its contacts with lived experience are always mediated by its own tools of analysis, those contacts are metadiscursive, at one remove, in the world of the signified rather than the signifier. The intelligence immobilizes and separates; it is the spirit that drives literary criticism, and that kind of translation which pursues an interpretative strategy. The procedures of the intelligence are also characterized by their adherence to ‘mechanism’ on the one hand, and ‘finalism’ on the other; where ‘mechanism’ concerns itself with structure, with positions and dispositions, networks and groundplans, the rationale of constitution, ‘finalism’ concerns itself with sequence, order, the direction of structure, with teleology. In order to capture a body lifting its hand from A to B, the procedures just described address, from the outside, the curve AB, analysing it into a series of positions, an order:

But mechanism and finalism would both pass movement by, movement which is reality itself. In a certain way, movement is more than a set of positions and their order, because it is enough to produce it, in its indivisible simplicity, for the infinite number of its successive positions and their order to be produced at the same time, with, additionally, something which is neither order nor position but the essential factor: mobility.4

The indivisibility of movement as movement, so central to all Bergson’s thinking, relates crucially, too, to our attitudes to translation. It is part of the reason why we promote the notion of metamorphosis at the expense of choice, and why we insist on the variational development of sense across items of language rather than the grouping of competing items around a targeted meaning. The problem for the ‘designer’ of translations is precisely how to capture the ‘living’ momentum of reading, how to capture the interwoven dynamic of the pre-reflective and the reflective, how to regenerate in the reader of the translation the constant activity of consciousness, how to avoid any suggestion that the target text is a post hoc interpretation of the source text, how to maximize the sense of something in mutational process. And this in turn entails a re-orientation of our notion of rhythm, now understood more as a mode of apprehension of the object than as a property belonging to the object, the rhythm of reading rather than of what is being read. What I envisage here is a notion of rhythm which is not accusative in nature, an it, a fact of text, but nominative/vocative, an instrument of reader/text dialogue, address, interlocution. The translator listens and speaks one text into another, not by automatic equivalence (alexandrine into iambic pentameter, sonnet into sonnet), but by experimental response and re-disposition.

If I emphasize rhythm as a mode of perception, of processing by consciousness, it is for three reasons. First, it is perhaps a perfect exemplar of Bergsonian movement. If I make that claim, it is because I distinguish fundamentally between the rhythmic and the metric,5 in a way, perhaps, not shared by other commentators who look upon rhythm as a freedom within, or a variation on, metre, to be described in essentially metrical terms (stress/accent, syllable). For me, rhythm is non-recurrent (irreversible), continuous, heterogeneous and qualitative; it is a variational weave of duration; one may speak of the duration that inhabits rhythm, but one should also say that rhythm is the very rhythm of duration. Metre, on the other hand, is a separable pattern (‘mechanism’, abstract); it is discontinuous (unitised), homogeneous (repeated units), and quantitative (measurable). Metre is a standardized sequence of units which parcel up/are parcelled up by chronometric time (rather than duration).

It is the multi-dimensionality of rhythm – deriving, as we have said, from the investment of the linguistic by the paralinguistic (intonation, tempo, amplitude, pausing, respiration, etc.) – which, second, ensures that it is physically incorporative of the reader, that it is, kinaesthetically, a whole-body experience. This is not to deny that metre will also produce kinaesthetic experience, but of a much more restricted kind; and while rhythm is that medium/energy/ force by which the reader is absorbed into the world generated by textual dynamics, as an agentive participant, metre is an analytical instrument which informs the hearing of the text and its modes of linear distribution, but does not pretend to embody the experiential making of, and responding to, the text.

Finally and third, and consequential upon the points already made, rhythm is a natural expression of the intuitive, while metre gravitates towards the mental habits of the intelligence. Intuition, that ‘divining sympathy’,6 has powers of empathetic penetration, which establish the contact of one’s own duration with that of another.7 What, then, is involved when the focus of the translator shifts from comprehension of the text to intuition of the text? What distinguishes an intuitive translation from an analytical or interpretative one? An intuitional translation grapples with rather more than the words of the text themselves, whose translation might turn out to be little or no different from a version supplied by the interpretative intelligence. What intuitional translation grapples with is the ‘theatre’ of consciousness as it processes text, the durational experience of a body in the thick of contingent, indeterminate, textual eventfulness, keeping track of its own flux.

In ‘Introduction to Metaphysics’, Bergson uses translation as an illustration of any analytical (empirical, rational), as opposed to intuitional,8 mode of apprehending a phenomenon:

analysis is the operation which draws the object back to familiar constituents, that is to say, constituents common to this object and to others…Every analysis is thus a translation, a development in symbols, a representation from successive points of view from which one identifies just so many shared features between the new object being studied and other objects which one already reckons to have knowledge of. In its eternally unsatisfied desire to embrace the object around which it is condemned to turn, analysis endlessly multiplies points of view, to complete the never completed representation, tirelessly varies the symbols to perfect an ever-imperfect translation.9

This account leaves us with the difficult task of reconciling our view of translation which is fundamentally Bergsonian in spirit with the views of Bergson himself, which tend to denigrate translation. It is easy to say that Bergson, like us, is implicitly attacking a view of translation which has surrendered the intuitional to the analytical, or, in my terms, which has surrendered durational reading experience to the immobilizations of interpretation, or the multi-dimensional and qualitative rhythms of the reading consciousness to the recuperation of mono-dimensional and quantitative textual rhythms.

But this large agreement conceals details of terminology and attitude that are more difficult to negotiate, largely because Bergson’s view of intuition seems to preclude any possibility of translational success;10 for Bergson, in fact, intuition is the apprehension of the untranslatable, the inexpressible, and translation, however self-multiplying, will always be second best.11 In presenting a new version of translation, a translation seeking to espouse the text-intuitional, how would we wish to take issue with Bergson?

Translation is not, as Bergson supposes, a quest for an ever-more proximate fidelity. Translation journeys away from the source text in an indefatigable exploration of the reading experiences its allows/begets, which are bound to be different with each reader and with each reading. We might disagree with Bergson and propose that these variations do render ‘the inner meaning of the original’,12 but one would need to interpret ‘inner meaning’ precisely as that which, in the source text, does not find an exteriority, that is to say, its invisible, its expressive exploitability, its translatability.13 Nor would we wish to think of the source text as the original. Thus, this kind of translation is not a representation of the original and does not trade in ‘symbols’, if these are to be understood as a metadiscursive treatment. And this version of translation does not operate in the world of the already known, translating the given with a given, a world that is circumscriptive; on the contrary, as we have said, translation is an ‘invalid’ practice-based research, a constant re-invention of what might be created out of intralinguistic and interlinguistic, intertextual and extratextual, cross-sensory and inter-medial activity.

But there are further qualifications to be added. If Bergson wishes to describe intuition as ‘the disinterested knowledge of an object one aims…to grasp in itself’,14 then there are three senses in which I would wish to hesitate or demur. Intuition is an existential sympathy which does not bring knowledge in the sense of cognitive information or identification of stable characteristics; it is, so to speak, shared experience, in all its vivid immediacy. It is ‘disinterested’ in its espousal of otherness, but it is a wedding, it has interests of its own, a mutuality of input into the momentums that the wedding itself blends. This then disqualifies ‘[which] one aims…to grasp in itself’, not because of the wedding alone, but also because there is no ‘itself’: there is a multiplicity of experiential encounters, all in the mode of becoming, so that an ‘itself’ is never more than an ever-changing virtuality. Finally, and in the light of these remarks, one should insist that translational language, as an intuitional language, is no longer the metadiscursive language of ‘symbols’ that Bergson imagines it to be and which it naturally is in ‘standard’ interpretative translation; it is no longer a representation or re-presentation or interpretation of the source text, nor the signified of the source text’s signifier; it is itself a signifier cohabiting, and collaborating in, the source text’s sense-generating duration; the target text draws its language from the same perceptual and psycho-physiological source as the source text.

But here, too, we need to be quite clear. Our preference, in ‘sense-generating’, for the word ‘sense’ over the word ‘meaning’ is guided by the need to speak of a signifying process itself caught in movement, in becoming. Meaning is altogether too much an objective, something arrived at, a conceptual substance, while sense allows a glancing, elusive, changing, kaleidoscopic semantic. To read and write in the spirit of duration is to treat the semantic not as a goal but as a passage, not as a combination or interplay of semantemes generated by language and presented for our inspection and consumption, but as the indivisible, un-decomposable foam of senses deriving from our own immersion in language as readers, reading into and across language rather than out of and away from language, towards the dictionary, towards a valid account.

But our disagreement with Bergson does not pertain to the concept of translation alone; it pertains, too, to the processing of linguistic sequence. Bergson concludes that ‘the mechanism of our day-to-day knowledge is of a cinematographic kind’;15 it restores movement to immobilized states, yes, but from the outside and in a form that is abstract and uniform. Bergson also suggests that we use language cinematographically.16 Reading seems to set words in motion rather as a projector sets images in motion; but this, suggests Bergson, merely repeats the illusion which underlies the cinematographic. Reading is not so much a triggering of motion in words as the eye’s passage through them, which leaves words as separate entities (dictionary entries) and allows them, as ‘imaginary stases’,17 to perpetuate illogicalities. We should not be led to believe that the movement of the projected spools of film have actually introduced movement into the frames of the film, that the scenes depicted in those frames have entered their own duration. They have not. They have been given succession but are themselves still immobile. But this seems to me a misrepresentation. In reading, we draw the sequence of language into our own duration, partly because we activate processes of anticipation and memory, partly because we harness the rhythms of language to our own rhythms of apprehension/ perception, and partly because our cognitive faculties are constantly busied with the multiplications and reconfigurations of sense (rather than with the procession of meaning). These attributes of the reading consciousness are all fully Bergsonian in spirit; it is just that his attachment to the model of a duplicitous cinematography, and his wish to increase its detrimental effects, prevents him from allowing them.

The same cinematographic truth, Bergson would argue, governs strings of words introduced into speech-flow by the reading voice. But he would be wrong. And he would be wrong for the simple reason that the voice fundamentally changes our perception of printed language, even if it is only reading printed language silently. There is, that is to say, a duration linguistically sui generis in speech that there is not in printed language. We might pick out, among others, four ways in which voiced language is a durational transformation of the written language. First, the values of apparently identical phonemes are paralinguistically/vocally differentiated where an IPA transcription would make no distinctions; as Edward Sapir points out: ‘Probably not one English speaker out of a hundred has the remotest idea that the t of a word like sting is not at all the same sound as the t of teem, the latter t having a fullness of ‘breath release’ that is inhibited in the former case by the preceding s; that the ea of meat is of perceptibly shorter duration than the ea of mead [because the latter is followed by a voiced consonant]; or that the final s of a word like heads is not the full buzzing sound of the s in such a word as please’.18 Second, the voice distributes the sounds of phonemes, to maintain speech-flow, where the printed language segregates them. Stephen Handel points out, for example, that ‘The spelling of the word cat is “c” followed by “a” followed by “t”. If, however, we try to cut out the “c” part from a tape recording, no unique section can be found. The “c” permeates the entire word acoustically, albeit not perceptually’,19 and further generalises: ‘The production system must cheat in order to get all the sounds out rapidly: movements appropriate to several successive sounds must be made simultaneously, and movements necessary to produce future sounds must be started early enough to ensure that the vocal tract will be in the correct position to make those sounds when they are required’.20 Third, speech, as we have seen, introduces the paralinguistic and prosodic into the linguistic; where the printed text is only a segmented language, vocal realization supplies a durational momentum expressed in so-called supra-segmental features (tone, intonation, dynamics (in the musical sense), tempo, pausing, etc.). Fourth, and finally, this suffusion of the verbal network by the paralinguistic indicates the informing of the text by rhythm, such that metre, the pre-vocal identification of the syllabic and accentual constitution of the verse is absorbed into the rhythmic as a raw material, as a particular and malleable dimension of its multi-dimensionality. Rhythm, then, is not just one feature alongside the multiple other features of the spoken text; it is the animating and shaping force that inhabits and drives all those features, the operating principle of the whole text in the reading mind.

In order to capture the elusive prey that duration is, in order to do its some justice in our translational practice, what options are open to us? We might, quite simply, accept that, by definition, we shall never be able properly to express duration or the activity of intuition, and accept, too, that we are bound to adopt analytical means as a way of building our ‘knowledge’ of the reading of verse. Bergson, after all, perfectly well accepts that analysis is a proper and valid use of the human intelligence, its ‘natural’ mode for apprehending reality, however artificial it is. We must merely be sure to acknowledge that it is only half the story, and be conscious of the ways in which it falls short. But we can also attempt to coax the analytical into deviating into the durational, principally by page-design, by a page-design which puts the known of language in doubt, which makes the voice constantly re-assess its modes of delivery, its segmentative habits, its phrasal groupings, its acoustic distribution. Page-design might become the instrument whereby what was text becomes a scenario, becomes a pre-textual scansion, or projection of vocalized text, inviting, by its very nature, multiple other scansions, because it embodies the truly possible, not a possible that retrospection identifies as a highly probable. So, the text is a pre-performance script. But it is at the same time itself a performance or a performativity, summoning other kinds of textual performance, other page-designs. In this way, the page outwits the trap of space and the spatialized; instead it acts as an invitation into time, it activates time. Where previously the scansion of a poetic text was a way of evidentially validating one kind of metrical reading, the text-as-scansion is designed to invite a ‘programme’ of (self-)investigative experimentations, or explorations, which supersede any notion of validity, but are not themselves self-superseding.

This, then, is now a language which we are encouraged to listen to differently, not simply in order to pick out, recognize, those acoustic elements already identified in the written text – alliteration, assonance, rhyme, iambic pentameter, the alexandrine, etc. – but, rather, to steep ourselves in the polymorphous meanderings of rhythm, and what it lives on in the way of phonetic modulations, accords and discords, crisp and drawled enunciations, the whispering and declamatory; these are not the incidentals of individual voices, which do nothing to change the underlying meaning of the text; these are investments of the text with voice, rather than vice versa, which actively constitutes the very substance of verbal duration. What agent, other than the speaking voice, can change language from a sequence or succession of separate lexical entities into a fused flowing, a flowing which incorporates pausing, and silence itself, into duration, into textual becoming, into the discourse of a speaking subject, into the integrated multi-dimensionality of rhythmic unfolding. Voice changes the very nature of printed language, acoustically, rhythmically, in the way it distributes sense rather than gathers meaning, in its paralinguistic animation. The prejudice against voice in the world of metrical analysis is firm and of long standing, and reflects a deep distrust of an uncontrollable, unquantifiable, unpredictable energy, which runs directly against the desire to establish linguistic fact in the printed text, which itself undergoes no change.

Let us then be clear. Bergson looks upon language as an impediment to our getting close to intuitional experience, to duration. Language has a natural tendency to serve analysis, to turn percept into concept, to make abstract and to generalize, and thus to travel away from immediacy of contact and from exactitude. Language converts all experience into versions of the already known, of available knowledge, and, as we have just seen, it suffers from the same delusions as cinematography: it supposes that words enter duration by virtue of being spoken, but it is actually only the voice that enters duration, using words – which themselves continue to exist as separable units – as its instrument. Our view is that Bergson’s thinking is unnecessarily pessimistic. But there are mitigating circumstances.

Bergson gives one of his fullest accounts of the capturing of duration in language towards the end of the second part of the introduction to his 1934 The Creative Mind: An Introduction to Metaphysics (La Pensée et le mouvant).21 Reading is the key: it is not to do with comprehension so much as with thinking one’s way into text by adopting the procedure of the author, and reading aloud is the best way to achieve this self-assimilation. Perception of the movement of discourse, direct communication with the author’s thought, derives from a vocal/dictional inhabitation of the text’s rhythm and punctuation:

To mark punctuation and rhythm as is proper, to take account of the temporal relations between different sentences of the paragraph and different phrases of the sentence, to follow, uninterruptedly, the crescendo of feeling and thought to the point musically noted as culminating, that is what the art of diction is first and foremost all about.22

The art of reading, in short, is the intuitional art of espousing the creative evolution of text. Elsewhere, in a lecture on ‘L’âme et le corps’ delivered in 1912, and collected with other essays and lectures in the 1919 Mind-Energy (L’Énergie spirituelle), Bergson fleshes out a little what his notion of rhythm entails. Rhythm is the indivisible movement that thought is and the words that emerge from this flux are like snapshots or film-frames. But words by themselves are generalised, abstract, unindividuated, impersonal: it is only rhythm and punctuation and ‘the whole choreography of discourse’23 that can animate them with a will, a direction, an individual nuance, a singular coloration. But rhythm itself is, to all intents and purposes, pre-verbal (‘and what can the rhythm of thought be but that of the hardly conscious, emerging movements which accompany it?’);24 rhythm does not derive from words, it is rather the reverse.25

This is a view of rhythm with which we have a great deal of sympathy, but with which our own view does not entirely tally. Rhythm is a mode of expression, but also a mode of apprehension: perception is an active faculty. Diction/reading aloud, in other words, is not a purely assimilative process; it is also an exploration of, and experimentation with, what the reader wishes for the words-of-the-text and what they seem to wish for themselves in this particular variational sequence. Thus, while Bergson’s case draws much on the assumption that words entail the substitution of concepts for things and promote ‘the socialization of truth’,26 our view is that words are things and that they look to the reading voice to achieve their potential complexity. Rhythm is not pre-verbal, a force passing through words and upon which words are invited to cast their light; rhythm is awakened by words, and, as a result, constantly animates and inflects sense, in such a way that words never fall back into default positions, that is, positions of ‘average’ meaning, of standard function, of generalised and abstract status.

The translational ambitions I have described are an abjuration of the notion of validity, in the belief that it is politically tendentious and untrustworthy. Validity assumes that compliance with certain predetermined conditions gives a document, an action, or an activity, legitimacy, justification, a warrant. In this sense, validation is a sifting process, a triage, which supposes that some things are state-condoned and licit, while others are not, or, further, that these things are only state-condoned if they fulfil demands expressly laid down by the state, where ‘state’ is to be understood as any organ which, among other means, exerts power through a body of concepts/lexical terms used as yardsticks of behaviour or licences for actions. In intellectual matters, the state is to be understood as the academic institution. To be validated, research (research-based practice) must be assimilated into state procedures. Translation, as we imagine it, falls outside the given pattern of validation: the authoritative establishment of the original text (source text), which must be preserved; the justness of the translation (judged by one’s peers); the translator’s own accredited status (special dispensations are made for poet-translators whose status is reckoned to be validation enough). My version of translation undoes these validations: translation is designed to destabilize the source text, to discompose it, by searching out multiple texts within it, the ‘invisible’, the expressive (re) configurations it makes possible; the translation is not preserving the source text in another language, but projecting it into a metamorphic becoming, into a future of continuous variation; and the translator is in no sense ‘qualified’, but is, rather, the common reader, whose translations are records of the experience of reading. In the terms of Deleuze and Guattari, this version of translation is rhizomatic in its unfolding, minoritarian and de-territorializing.

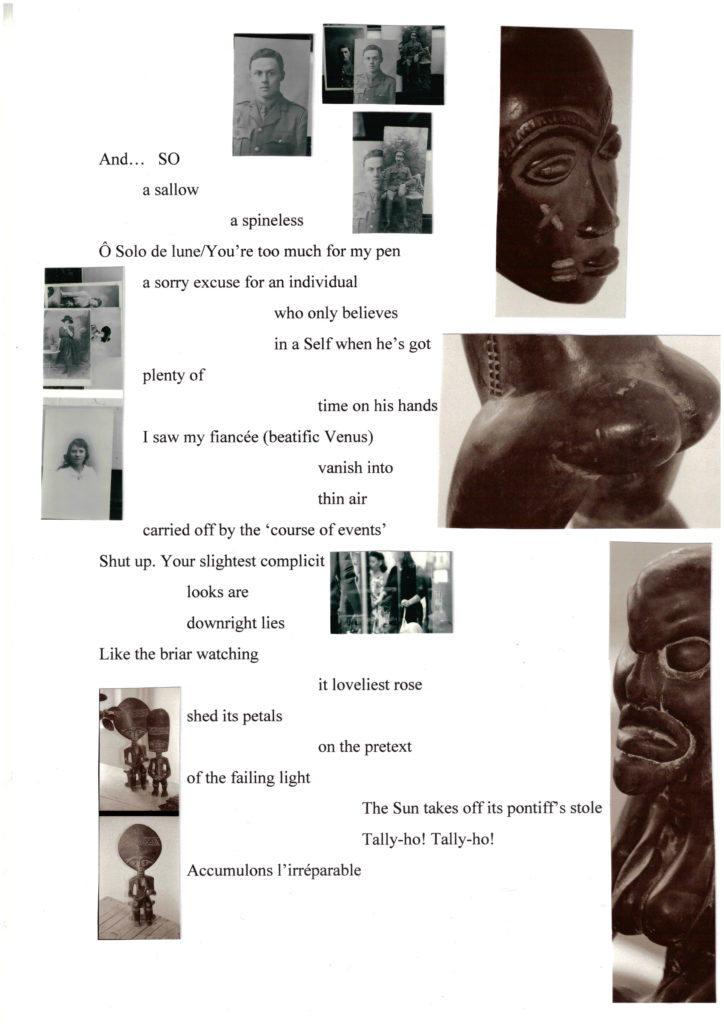

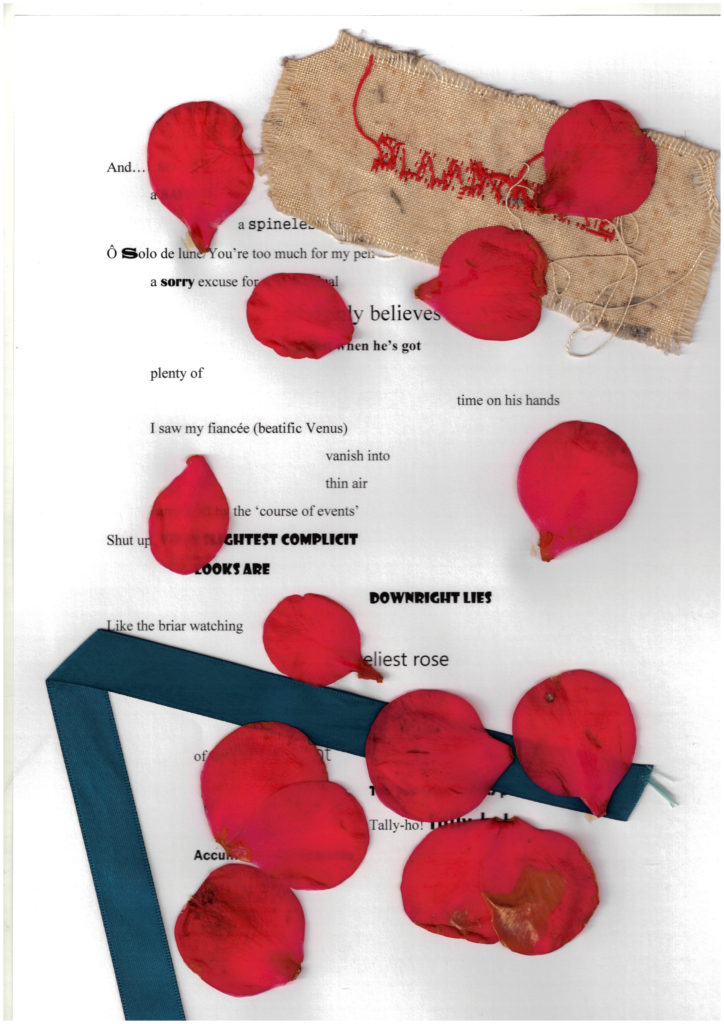

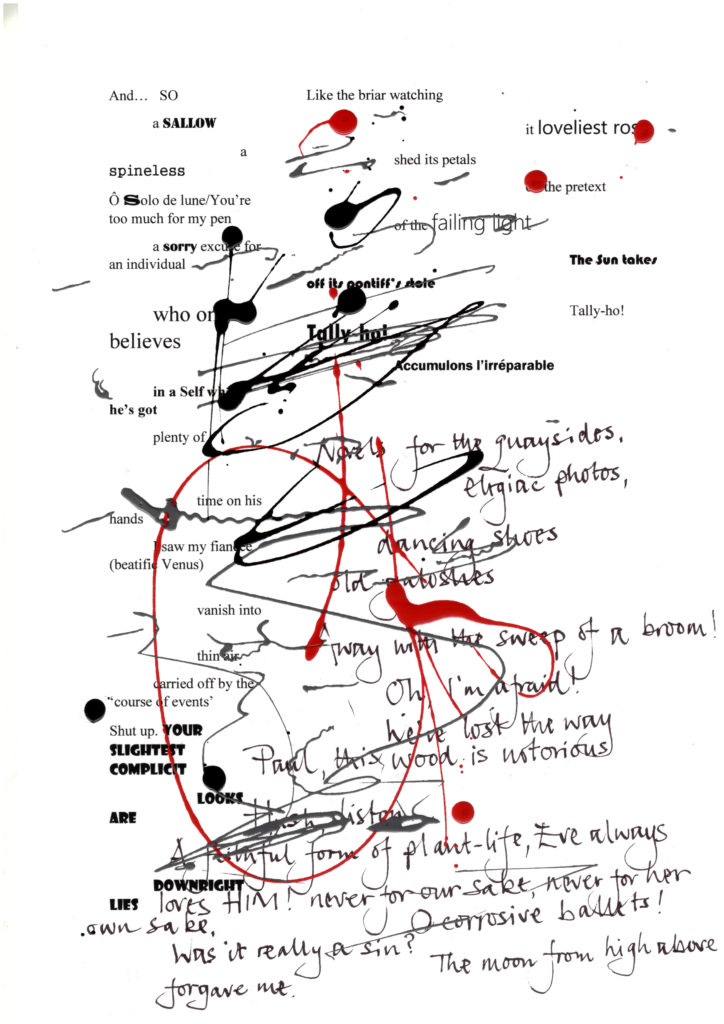

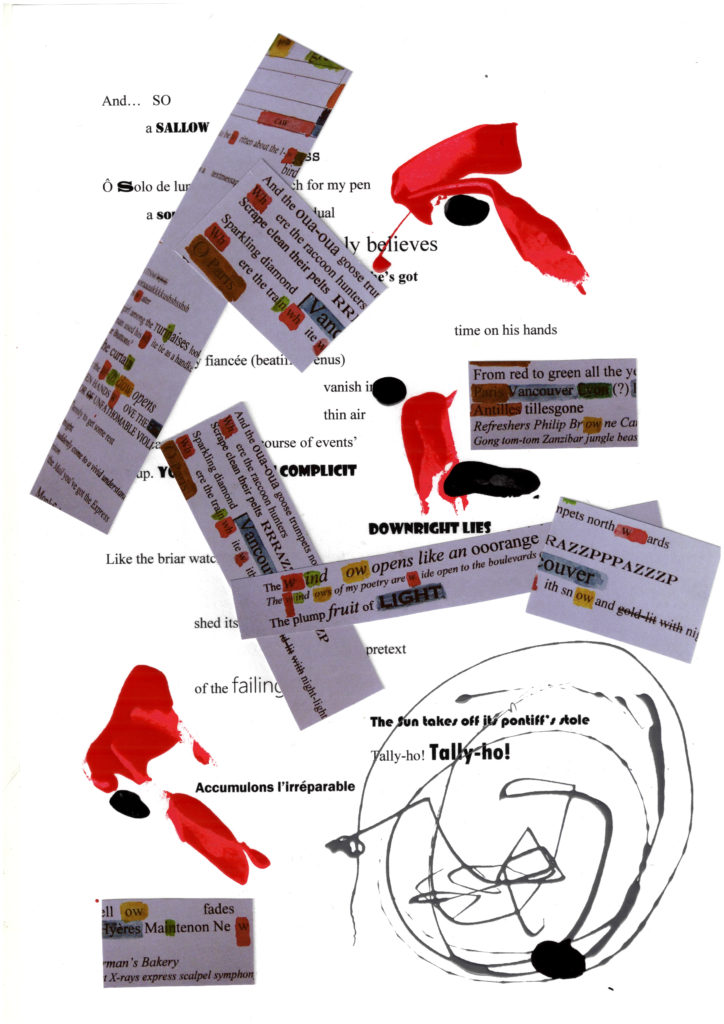

As a final, brief piece of supporting evidence for this anti-validity argument, I would like to present four ‘renderings’ (Figs. 1–4) of some lines from Jules Laforgue’s 1890 ‘Dimanches (I)’ (Derniers Vers):

Ainsi donc, pauvre, pâle et piètre individu

Qui ne croit à son Moi qu’à ses moments perdus,

Je vis s’effacer ma fiancée

Emportée par le cours des choses,

Telle l’épine voit s’effeuiller,

Sous prétexte de soir sa meilleure rose.

Even as I produce the translation, the senses of the words, the utterances, are inflected by my associated consciousness of other lines and collocations from the Derniers Vers, which are feathered into the text. This process is orchestrated against, and made more complex by, the textual re-dispositions and the heteroglossia of different typefaces. And the larger, passing preoccupations of this particular reader – photographs, painted figures, collaged materials – become an added layer of perspectives on these lines, which translation absorbs into the text in such a way that the play of both sense and the physical senses is further reconfigured. Both the reader and the text are being constantly re-woven by new inputs, new associations, new memories, in a process which converts collage (inserted fragments) into metamorphosis, into continuous variation. And these versions can be read in any order, the principle of variation will work just as well. In Fig. 1, I think the lines photographically, drawing on a collection of WWI portraits, African art, the odd contemporary street scene; in Fig. 2, I visit relics: not rose-petals but camellia-petals with their added literary/operatic overtones, a name (‘Fidelle’) sewn on coarse cloth, but on the reverse, so that it is both illegible and as if unravelling, a discarded piece of ribbon; in Fig. 3, which, with its mention of ‘Novels for the quaysides, elegiac photos’ (from Laforgue’s ‘Lament of the Barrel Organ’, in Graham Dunstan Martin’s translation from 1998), relates to Figs. 2 and 1, handwriting and a tracery of enamel paint enact a directly gestural response, opening up the text to kinaesthetic drives and the imprinting of the graphological; and, in Fig. 4, while the red enamel paint picks up the camellia petals of Fig. 2, the blue, collaged extracts from my translation of Apollinaire’s ‘The Windows’, a poem dedicated to the work of Robert Delaunay, provide a construction of skylights in the text, opening on to a mobile world of relentlessly changing sensation, which makes dramas of the heart seem peculiarly outmoded.

1. Clive Scott, 2017, print, photographic fragments, 21.0cm x 29.7cm.

2. Clive Scott, 2017, print, camellia petals, ribbon, piece of rough cloth, 21.0cm x 29.7cm.

3. Clive Scott, 2017, print, ink, enamel paint, 21.0cm x 29.7cm.

4. Clive Scott, 2017, print, enamel paint, collaged hand-coloured textual fragments, 21.0cm x 29.7cm.

Practice-based research allows one to make claims for a version of translation that researchbased practice occludes. In fact, practice-based research reverses the assumptions on which research-based practice is based. For research-based practice, research establishes the facts, and the discipline develops the appropriate methodologies for interpreting and applying them; the scholar becomes the agent of the discipline’s outworking. But what if reading does not primarily serve the development of an institutional book-culture based on literary categories, hierarchies, history? What if the value of reading is reckoned to lie in existential objectives of the kind we have outlined, including self-coordination, self-improvisation, an intuitional activity in which reading, as a mutual undertaking between author and reader, constantly expands the field of energies released by a text? In this latter world, there are no facts, no methodologies or recognized procedures, only an accumulating body of evidence, marshalled by practice-based research, the promise of an inexhaustible inner duration, of a becoming, driven by the rhythms of creative consciousness. Practice-based research offers itself, then, as the repository both of countless contacts between the existential energies and horizons of different languages and the kaleidoscopic and inexhaustibly heterogeneous experience of reading subjects.

1. As Henri Bergson puts it: ‘However, language designates states with the same words for everyone; thus it has only been able to fix the objective and impersonal aspect of love, of hatred, and of the countless feelings which stir the soul’, and see: Henri Bergson, OEuvres, ed. André Robinet, intro. Henri Gouhier (Paris: PUF, 1984), 108–09. I give all quotations from Bergson in my own English translation; page references indicate the locations of the French originals.

2. Idem, 498.

3. Translation is an activity that necessarily takes place in a reality in which nothing repeats itself; as Bergson puts it: ‘If every thing is in time, everything changes internally and the same concrete reality never repeats itself’, and see: Idem, 533.

4. Idem, 572–73.

5. Clive Scott, Translating the Perception of Text: Literary Translation and Phenomenology (London: Legenda, 2012), 111–32.

6. Bergson, OEuvres, 644.

7. Idem, 645.

8. Just to remind ourselves of one of Bergson’s succinct definitions of intuition: ‘“Intuition” here is the sympathy through which one penetrates the interior of an object, to coincide with what is unique and consequently inexpressible about it’, and see: Idem, 1395.

9. Idem, 1395–96.

10. ‘All translations of a poem into all possible languages can add shades of meaning to shades of meaning as much as they like and, by a kind of mutual retouching, with reciprocal correction, provide an ever more faithful image of the poem being trans lated, but they will never render the inner meaning of the original’, and see: Idem, 1395.

11. ‘A representation from a certain point of view, a translation made with certain symbols, remain obstinately imperfect when compared with the object which is the subject of the point of view or which the symbols seek to express’, and see: Ibidem.

12. Ibidem.

13. ‘Translatability’ here has a meaning akin to the meaning it has in Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Task of the Translator’. A text’s translatability is its desire to be translated, so that its life can attain ‘its latest, continually renewed, and most complete unfolding’. In this sense, a translation has the ability to take a text beyond its own limits. But in order for that to be so, the text must already possess a translatability, must have the inherent capacity to re-discover itself in another language. See: Walter Benjamin, ‘The Task of the Translator,’ in Selected Writings I: 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996), 253–63, quote on 255.

14. Bergson, OEuvres, 1410.

15. Idem, 753.

16. Idem, 759.

17. Ibidem.

18. Edward Sapir, Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech [1921] (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1949), 43.

19. Stephen Handel, Listening: An Introduction to the Perception of Auditory Events (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 2.

20. Idem, 134.

21. Bergson, OEuvres, 1326–28.

22. Idem, 1327.

23. Idem, 849.

24. Idem, 850.

25. Idem, 849–50.

26. Idem, 1327.