TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER

Elisabeth Lebovici, translated by Naomi Vogt

To cite this contribution:

Lebovici, Elisabeth, translated by Naomi Vogt. ‘TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021), http://www.oarplatform.com/expose-show-demonstrate-inform-offer-1/.

PREAMBLE

This text was originally the fourth chapter of the book Ce que le sida m’a fait (What AIDS did to me).1 It connects the city of New York, and particularly the Lower East Side (with some forays into Times Square), with the transformation of the nature and concept of contemporary art exhibitions. My direct experience of the exhibitions I discuss here left its mark on me, as did an exhibition organized years later by Douglas Crimp and Lynne Cooke: Mixed Use, Manhattan (Reina Sofia, 2010). These exhibitions set about examining how, in the midst of the city’s recession since the 1970s, Lower Manhattan became a central scene for the experimentation of new artistic practices and forms of sexual contact. Thus, this chapter seeks a genealogy for the rather exemplary forms of display manifested through the different versions of Group Material’s AIDS Timeline, at the turn of the 1990s. This genealogy is structured by the idea that the exhibition site can also be a context of and for sociability and public assembly. At a time when HIV/AIDS provoked panic and silence, the time and space of certain exhibitions opened themselves to speech, to information, to exchange, to protest, in short, to the epidemic’s political visibility.

All images used for this translation are scanned pages excerpted from Ce que le sida m’a fait, published by JRP Ringier et La maison rouge in 2017.

* * *

Our mourning strives to be public, and to engage public institutions, because it is in the public domain that the value of the lives of our dead loved ones is so frequently questioned or denied. Thus the epidemic requires a public art, which might adequately memorialise and pay respect to our dead. — Simon Watney, ‘Memorializing AIDS,’ Parkett, 1993.

Every genealogy is a fiction. There is no such thing. There’s only one genealogy. It takes place in our dreams. Every specific genealogy is a fiction. — Jill Johnston, ‘Untitled’, Marmelade Me, 1998.

‘The East Village stinks. Garbage covers every inch of the streets. The few inches garbage doesn’t cover reek of dog and rat piss. All of the buildings are either burnt down, half-burnt down, or falling down. None of the landlords who own the slum live in their disgusting buildings. In the winter when temperatures average 0º, these buildings have no hot water or heat, and in the summer at 100º average, roaches and rats cover the inside walls and ceilings.’2 This is how the astounding writer Kathy Acker described the area of Manhattan situated below 14th Street on the urban grid. Since that time, the East Village has undergone a full process of gentrification.3 The word – first coined in 1964 by the sociologist Ruth Glass regarding neighborhoods of London – was also used by Acker’s friend, the writer and lesbian activist historian of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power), Sarah Schulman. ‘Kathy is emblematic to me of one of the stages of gentrification, the forgetting of pioneering artists and their innovative contributions’, she writes. ‘Her death, in the midst of the AIDS crisis, was another elimination of free space, another shrinking of the community of non-corporate thinking. Another victory for the power of homogeneity’.4 For Schulman, the gentrification of minds occurs simultaneously with the urban policies that follow real-estate speculation. Both bear the responsibility for discarding people with AIDS – those who are dying, their lifetime belongings, the partners of those who are dead, as well as gays of color, lesbians, and socially fragile human beings who cannot afford apartments at market rates. Gentrification reshapes the material of lived urban experience. It affects the ways in which people make contact, think, and interact, restricting the availability and viability of the ebullient, inventive forms of culture that are jointly created through the mix of residents and their neighborhoods.

Traditionally, the East Village and more broadly New York’s Lower East Side were rallying points for populations in transit, for refugees of various origins fleeing wars, pogroms and poverty, and for gender minorities. This geographic area, described by Acker and Schulman, comprises the East Village proper, Chinatown, Little Italy, Tompkins Square, Astor Place, Knickerbocker Village and the ‘Bowery’. From the 1970s on, these were largely immigrant neighborhoods where Italian, Polish, Romanian, Ukrainian, European Jewish, and Chinese communities were brought together. In the process of adapting to the dominant culture, they borrowed from other immigrant cultures engaged, like them, in mechanisms of resistance, interaction, and friction. Jewish performer Harpo Marx, for instance, first learned the ropes of performance by engaging with a Chinese ritual drama, The Yellow Jacket, a combination of traditional music hall and Cantonese opera. These migrant populations were housed in tenement buildings, rental constructions in brick that were relatively narrow and often low-rise – five to seven stories tall – and erected on cramped lots. The tight alignment and confined living conditions of this type of housing, along with the absence of air and light, were documented as early as 1890 by the journalist Jacob Riis. The neighborhood long remained a pocket of poverty. This condition deteriorated when two financial crises (1929, 1987) and the near bankruptcy of New York City in 1975 delayed the fulfillment of promoters’ whims. And yet, between Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 and the 1988-89 recession, building programs had taken an aggressive turn. The sale of ‘assemblages’ – in essence, devastated house blocks which the city had left to rot, coupled with a tax exemption for the construction of luxury flats – provoked the forced displacement of ill and impoverished residents. Landlords who could no longer make their investments profitable with the low rents chose to abandon buildings. Deprived of housing, hundreds of people found themselves living under bridges, in the streets and parks or in shelters, vacant lots, and the city’s underground.

Whether or not one has a home often draws the decisive line between living and withering. But it is not only a matter of having a place to stay; one must also be able to stay alive and to survive in it. Owners developed tactics that ranged from making financial offers in exchange for vacating the premises, to bypassing maintenance or doubling the rent unlawfully, to verbal and physical harassment. The municipal authorities were accused of spreading the epidemic due to the neglect of garbage collection, building inspection, and fire safety. ‘In New York, life masquerades as pathology’. After reading this graffiti inspired by a Lewis Munford quote in the toilets of Strand,5 the second-hand bookshop where he worked part time, photographer Ken Schles decided to confront his everyday life, namely the place in which he lived. A former student of Lisette Model and Hans Haacke at Cooper Union, Schles inhabited an abandoned building on Avenue B. A rat hole. AIDS, drugs, and violence were killing his generation. In 1988, he published a photobook and called it Invisible City.6

The housing battles in the Lower East Side (which date back to the construction of ‘First Houses’ in 1935)7 spawned an inspired following throughout the 1980s. The debate was focused on property, accessibility, the availability of public space, and the allocation of governmental subsidies to private investment and public housing. These issues gave rise to an array of local activisms. Actors of a conflict emerged: the young homeless people occupying Tompkins Square Park, regularly removed with violence by the police,8 the squatters of abandoned homes turned into ‘shooting galleries’, the older residents, the tenants, the lessors and the owners, the ‘developers’, as well as those who put their own bodies on the line in attempts to restore their homes (because of ‘homesteading’, which consists in granting rights on a building in exchange for refurbishing it), without forgetting the homeless who camped on the Bowery.9 All took part in a permanent conflict hinging on the political definition of the ‘neighborhood’.10 Through this word, an area becomes legible in terms of vicinity – physical proximity as well as social texture.

For artists who resided there, the stakes were high. ‘For $225 a month, I live in a slum with my two kids and two hamsters’, Judy Rifka told me in 1980. But the issue mobilized artists as artists too. Already in 1972, the sculptor Robert Smithson had declared that ‘art should not be considered as merely a luxury, but should work within the processes of actual production and reclamation,’11 a singular word evoking recuperation, retrieval, the conversion of a terrain. Ever since her Maintenance Art Manifesto in 1969, the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles dedicated her artistic activity to making visible both maintenance processes and the handling of waste, which was always expanding in public space. Thus in the early 1980s, the conditions for a strategy of reclamation were present in New York, a city where entire populations had been thrown onto the pavement by real-estate politics, cuts in anti-poverty programs, and the liquidation of several psychiatric hospitals. Following Reagan’s election, the pruning of public subsidies did not spare the arts, either. Unfailingly treated as strangers in the very streets which they had populated for so many years, the ‘artistic intelligences’ – a reference to the artists and craftspeople rallied during the 1871 Paris Commune12 – eventually began to pool their political imaginations.

In her film The Man Who Envied Women (1985), the choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer brought a feminist nuance to the reclamation strategy. The latter was sometimes taken all the way to court by members of Manhattan’s artistic community. Rainer superimposed recordings of public hearings about the Lower East Side with shots of Donald Judd’s sculptures and Leon Golub’s paintings, two white male artists who were strongly involved in political struggle. In this way she uncovered certain contradictions at the heart of their activism. Indeed, reclaiming a space always implies subjecting someone else to its loss. As the scholar Peggy Phelan suggests, ultimately this film explores the effects of the battles for urban spaces which, paradoxically, were setting artists – vastly white – against the predominantly non-white working classes. ‘Almost overnight we met the enemy,’ explains Trisha, a protagonist in the film, ‘and it was us’.13

Image 1

Image 1

Image 2

Image 2

Indeed, the Lower East Side was anything but a white cube. Within the area, variants of cultural radicalism practiced by racialized minorities had flourished. In 1970-71, the Basement Workshop Collective was formed by Asian artists and poets. From the 1960s on, cramped apartments became a place of black production and assertion, through the first African theater of the poet and therapist Rashidah Ismaili-Abubakr, the Negro Ensemble Company (a black youth and cultural center), publications such as Freedomways, Valerie Maynard’s open-air arts and craft courses, and the bars where Archie Shepp performed as a neighbor.14 It is here, at the New Federal Theatre, that the plays of Amiri Baraka a.k.a LeRoi Jones were produced. It is here, also, that Ellen Stewart opened La MaMa complex on East Fourth Street, and that painter Joe Overstreet and his wife Corinne Jennings created in 1974 on Second Street East the alternative gallery Kenkeleba House.

Part of the Lower East Side – notably Alphabet City, with its A, B, C, D avenues – became a place of assertion for Nuyorican cultures. Hence the term Loisada, derived from Spanglish pronunciation, to describe the decrepit quarters where, from the end of the 1970s, Latino and African-American families lived next to poets and musicians, graffiti artists, rappers, but also dealers and bad boys. At the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, a space of expression was forged for oral poetry. One of its pillars was Miguel Piñero, an author who had written most of his texts and plays in prison. In A Lower East Side Poem (1985), he demands that his ashes be dispersed within the bounds of the barrio, the neighborhood described as a field for identities that rebuff binary choices, be they about race, nationality, or gender. He hopes his remains will crash where ‘the hustlers & suckers meet’, where ‘the faggots & freaks’ stand ‘from Houston to 14th Street, from Second Avenue to the mighty D’.15 Not far from there, in Ridge Street’s flat 9 at the corner of Stanton Street, lived the flamboyant Martin Wong.16 Established in New York since 1978, he painted brick walls relentlessly throughout the eighteen years of his life on the Lower East Side – brick by brick. They made up the frame of public and private life, from facades to interior walls. He also painted the communication codes used by minorities – sign language, astrology symbols, graffiti, calligraphy, tattoos, sexual signaling – which overlapped with his erotic inclinations. The latter surface through depictions of strong men – the prisoners, policemen and firefighters who populate his visual culture as superheroes, and where Piñero sits front row.

In contrast to SoHo (South of Houston) and its distinct industrial architecture, with cast-iron housing and wall-less loft levels, the Lower East Side was a place initially populated by poets, performers, writers, directors, and musicians. Witness John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Joe Brainard and John Ashbery, Charles Ludlam, Jack Smith, Taylor Mead, or Ron Rice. There, they found contact zones with Latino, Cuban, and Caribbean cultures, traces of which lingered on in various experimental and explicitly queer productions, and in works considered foundational to queer practices today.17 Here, two histories call for cultures and figures to converge; their respective forms of ‘visual excess’ come with a revision of the internationalist avant-garde model, which had rebuked vernacular forms. Witness allusions to South-American movie stars and their transvestite impersonations, the relocation of Middle-Eastern and Spanish motifs in Smith’s films, or performances in John Vaccaro and Ronald Tavel’s The Playhouse of the Ridiculous, followed by those in Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous and, finally, the recycling of Latino cultures, which were no more accepted than the cultures of sexual minorities. Mario Montez, a superstar for Smith, Rice, Andy Warhol, and Hélio Oiticica, embodied the escape from naturalized visions of Puerto Rican masculinity, installing in its stead cross-dressing practices and the undecidability of genders and borders.

One border, however, stood: the one we erected in front of the bourgeois, the white collars and the stuffed shirts, and which we made a point of honor not to cross.

Rachid, whom I met while he was shooting a film with Teri Toye and Rudy Laurent, had never gone anywhere above 14th Street. (Toye would become the first transgender model of the period; Laurent, an actor who trained with Antoine Vitez, directed us on stage in No Trifling With Love – Alfred de Musset’s On ne badine pas avec l’amour – which we presented in the spring of 1981 at the Braathen/Gallozzi gallery). Below 14th Street, an alternative city could be outlined, described in turns as ‘bohemian’,18 rough, a Beirut in ruins, or zone of Roman decadence. Indeed James Nares’s Super-8 costume drama Rome 1978 formulated an analogy between Caligula’s reign and Downtown Manhattan. But the actresses and actors (musicians, artists and performers including Lydia Lunch, David McDermott, James Chance, John Lurie, Eric Mitchell, Judy Rifka, Jim Sutcliffe, Lance Loud, Mitch Corber, Patti Astor, Anya Phillips) never took this motif seriously and snickered throughout their performance. Thus, rather than a blank slate, archaeological stratification (so to speak) was at stake in these zones. Until galleries began penetrating the area – by 1986, 176 had appeared – this part of town had mostly bred makeshift spaces, such as basements and parish halls, or Bill Rice’s boutique and backyard. Turned actor at age fifty, Rice appeared in a bunch of Super-8 films (and plays such as the No Trifling With Love in which I acted).19 Having become one of the last tenants of a building on East Third Street, he made his asphalt ‘garden’ available to the various shows, readings, demonstrations, events, and screenings that were already happening around him. They were advertised through photocopied or re-photographed flyers, which I have kept. It is they that give me my memory back, along with my dog-eared copies of local papers: the East Village Eye, launched in May 1979; and Baseline: ‘It’s all true’. It was the neighborhood’s megaphone, its free radio, with its tons of static. Behind the duotone-printed, sometimes neon-colored cover, various forms of graphic expression were melded in cut-ups, which could overlap or be superimposed. The editor wanted it a freed zone. Walter Robinson, who came from Edit DeAk’s Art-Rite magazine, encouraged artists – such as Jane Dickson, Barbara Kruger, and Jenny Holzer – to intervene in it directly. The musician James Chance made the first cover: he and Lydia Lunch were two stars of this publication. David Wojnarowicz contributed a text. At any given time, one could read a review by Gary Indiana on VALIE EXPORT or Werner Schroeter, a column on the electric eye by Willoughby Sharp, or a user manual on how to self-organize an exhibition in a park. Quoting Jorge Luis Borges, Richard Hell wrote long texts from his position within the rough musical underground. Cookie Mueller wrote a medical section. As everywhere else in the neighborhood, the women who wrote were also those about whom columns were written; and the women who acted in films were also playing music; those who were beheld were also casting their own gaze. The unpredictability of roles remains one of the pleasures of that thing we no longer dare call ‘crossover’ or ‘interdisciplinarity’.

A more fortunate expression would perhaps be ‘Schizo-Culture’, coined by William Burroughs and used by Sylvère Lotringer and John Rajchman when they were professors at Columbia University. In 1978, they titled an issue of their journal Semiotext(e) after it. The term refers not to clinical schizophrenia but to ‘the fact that the culture is divided up into all sorts of classes and groups, etc., and that some of the old lines are breaking down. And that is a healthy sign.’20 In the now cult issue, a fire of confusion and disruption was lit by Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Guy Hocquenghem, Jean-François Lyotard, Kathy Acker, Jack Smith, Martine Barrat, the filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow, and the artist Denise Green. But the same can be said of the many women and men who performed at the Mudd Club, which opened in 1977 on 77 White Street. The owner, Steve Mass, even invited Keith Haring to open a gallery on the second floor.

My other favorite issue of Semiotext(e) is ‘Polysexuality’.21 Within it too the texts were multifarious in nature. Leafing through the pages of ads, papers, flyers and tracts, we see the obsessive, tireless reprise: sex. The word was on everyone’s lips, whether it referred to an event, an exhibition, the nth sado-masochistic film variation, the feminist projects that were at the time broadly using psychoanalytical terminology, or the character sporting a salient platinum blond quiff named John Sex (1956-1990). The Erotic Art Show was one of the first exhibitions organized by Haring in the cellar supplied by the Holy Cross Polish national church and re-baptized Club 57. It is where Sex performed with his snake Delilah. He performed increasingly in the wake of the launch of the Pyramid, the gender performance cabaret. Practice, before theorization. Pyramid is where the first drag king competition happened. And it is at the Pyramid, again, that the genderqueer activist Leslie Feinberg chose to be filmed while she explained the intersectionality of her own position, as a person subjected at once to transphobia and homophobia (Outlaw, 1994). Not far away, in 1982, the WOW Café (Women’s One World) was opened following the second edition of the eponymous itinerant festival. It presented itself as a ‘City of Women’, open to any kind of woman-on-woman aesthetic – particularly the most anarchist and chaotic ones. But showing up was not enough to belong. Something similar to a long corridor was divided in two by a kitchen – with the hall on one side and the dressing rooms on the other. The space framed a revival of the lesbian feminist ‘scene’, here a term to be taken literally. From performances to unpredictably titled balls (‘I Dreamed I Paid the Rent in My Maidenform Bra’), every woman was encouraged to take action. Here, the Split Britches (Lois Weaver, Peggy Shaw, Deb Margolin) and performers Carmelita Tropicana and Holly Hughes cut their teeth. In 1983, the latter performed her version of The Well of Loneliness, after Radclyffe Hall’s desolate 1928 novel, turned Well of Horniness. As Sarah Schulman observed, ‘it has taken over 65 years for historians to reacknowledge what the community knew all along, that lesbians were at the centre of radical organizing on the East Side, and that their relationships influenced radical politics and strategy.’22

In her texts, Kathy Acker addresses the theme of sexuality in order to question what belongs to the private or the personal – a search for ‘one’s self-truth’. To do so, she mixes these motifs with the tropes, and perhaps even the stereotypes, of gender. Obscene language irrigates her writing, which she borrows or juxtaposes to other, less obviously sexual forms. The latter thus become ‘contaminated’ by way of a coupling, for instance to fragments of Sade’s Justine. The produced effect is a reformulation of well-rehearsed debates around the reader’s role – the figure that is positioned, in classical narrative structure, as external to the text. The language of sex allows for the articulation of a desire, or a rejection, and their activation within the reader. The reader is turned spectator and placed at once outside and within the text: in short, at the threshold, always about to exit or enter. Acker’s practice ought to be compared with that of Wojnarowicz when he, as theorist Jennifer Doyle suggests, ‘deploys writing in order to force the spectator to become a reader, and that reading is hard because the text is written as a breathless rant.’23 Here is an example: ‘I’ve been looking all my life at the signs surrounding us in the media or on peoples lips; the religious types outside st patricks cathedral shouting to men and women in the gay parade: “You won’t be here next year — you’ll get Aids and die ha ha” . . . there’s a thin line a very thin line and as each T-cell disappears from my body it’s replaced by ten pounds of pressure ten pounds of rage and I focus that rage into non-violent resistance but that focus is starting to slip my hands are beginning to move independent of self-restraint and the egg is starting to crack […].’24 This long flow of words by Wojnarowicz has been used multiple times – filmed, read out loud, recorded, broadcast, turned into a ‘multimedia’ written form and mode of disobedience and disrespect precisely towards a fully written destiny, towards anything definitive that would put writing away as a discrete object, into a determined library shelf.

‘Piles of Trash.

Impersonal

Street is a Lover To Me’25

1979. The year I arrive in New York. Sol LeWitt composes On the Walls of the Lower East Side. Grids of photographs, 666 of them squared to the same format. All are in color, taken (with a Rolleiflex 2 ¼’’) in the neighborhood streets, including the entrance of 117 Hester Street, where LeWitt occupies a loft. All frame, often quite tightly, graffiti and inscriptions painted or posted onto walls. In these images, streets speak languages: English, Chinese, Spanish, Spanglish, Yiddish, Hebrew, and ‘sign languages’, if one may call the numbers and signatures of graffers that. Mostly, these are nicknames and sobriquets in embellished letters, sometimes accompanied by toponyms, ideograms, phone numbers, fragments of frescoes, public notices, signs, and piercing and often radical political declarations. Each wall unit with its text is isolated in a square photograph, before being integrated to the modular overarching composition. But how? The series’ structure does not seem to reference the topography of travelled streets, nor does it prescribe a direction of reading. Beyond the absence of hierarchy among the different units – none of which is ‘worth’ any more than another – urban disobedience is implied both by the iconography (the insurrection of walls) and by the lack of conformity between the spatial organization of the images and a given plane of reference. Here too, the viewers’ exteriors are drawn in. It is their bodies, your bodies, our bodies that produce the narrative of these wall drawings, drawings that are effectively made by the street – the street and its ways. LeWitt’s photo compositions, like the writings of Acker, are tracking shots without the cinema, without film; tracking shots that dispense both of the technical operations which normally produce them and of the continuity of a gaze which they usually imply. What they retain, however, is the potential for de-centering, for the strolling of the flâneur and, in the spirit of Viriginia Woolf, for the ‘street hunting’ of the female passerby (indeed through détournement, the ‘street haunting’ formulated by Woolf morphs into a hunt). In the impersonal trash-filled streets that American lesbian poet Eileen Myles turned into fertile ground, nameless people circulate. In English, the word ‘nobody’ can translate as ‘without body’. And I am one of those no-bodies when I move among my archives. I do not appear in the photographs, I am not ‘tagged’ in the newspapers, on the websites, or in the texts, which I have not written… Many of the friend-bodies that have accompanied and loved me, corresponded, conversed, and shared what I saw with me, have disappeared. So, more than thirty years later, I find myself wanting to describe what this surviving spectator experienced physically.

Image 3

Image 3

Image 4

Image 4

Image 5

Image 5

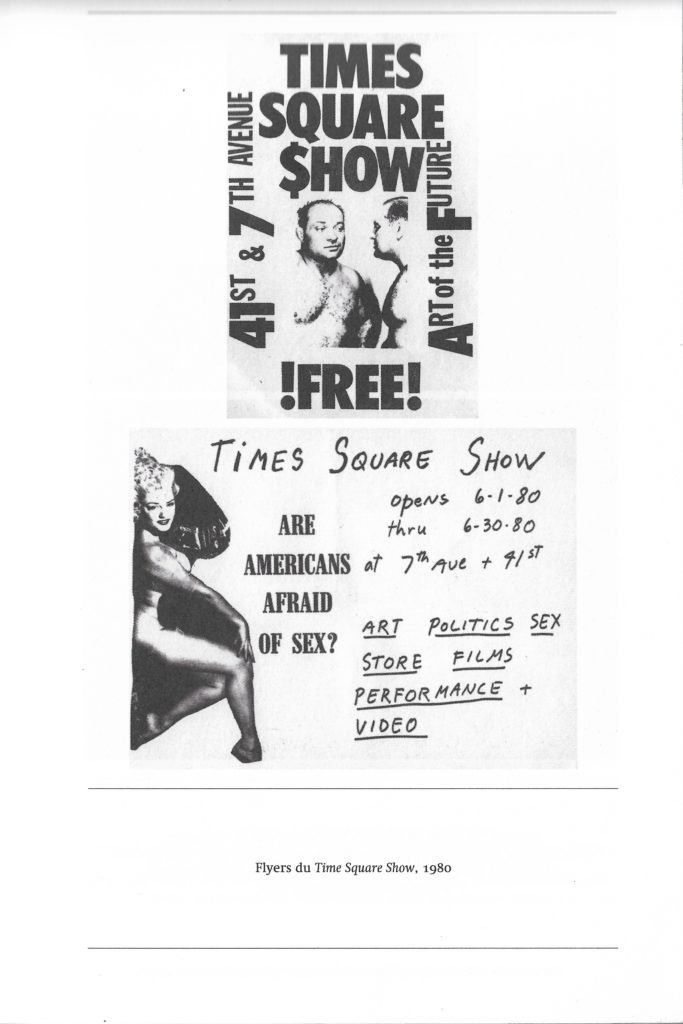

When I brutally changed the subject of my doctoral thesis – from a study of the Journal of Thomas Blaikie, a late eighteenth-century Scottish gardener, to L’Argent dans le discours des artistes américains, 1980-1981 (‘Money in the Discourse of American Artists, 1980-1981’), I was asserting the field of my inquiry: the here and now which, through my writing, I can now hear and see. This decision, which drew me inside the New York I landed in, was first and foremost the consequence of an exhibition. The Times Square Show augured my transformation into a (hopefully emancipated) spectator.26 Thus I began: suddenly last summer…

Times Square in 1980 concentrated the squalid and the marvelous – a territory made up of adult movie theaters, sex shops, topless bars, fast foods and various appliance stores, animated by the ceaseless traffic of neon signs, cars, pedestrians, and underground wagons. 8000 pedestrians per hour. Indeed, Times Square had been the object of a ‘century-long struggle for dominance between three industries: real estate, the performing arts, and sex’. In 1980, the neighborhood was given over to a tight fight between ‘queer freedom, advertising overkill, cultural diversity, and brutal urban violence’.27 Nested in this land of all promiscuities stood a massage parlor, one among many others. On 201-205 West 41st Street, between the 1st and the 30th of June and for almost twenty-four hours a day, a former brothel hosted an exhibition. Open to all – passersby, prostitutes, dealers, art clients – it kept track of its own environment. For it, artists built a ceremonial archive. Times Square is no doubt New York’s first and last public ‘square’, in the European sense of the term. And indeed the exhibition functioned as one. It saw itself as a replica, in a seismological sense, of a place crossed by different energies. It translated those energies into figurations, including ‘knives and guns and money and dirt and cocks and cunts and blood and gore’. Less enthusiastic, Lucy Lippard accused the exhibition of imposing itself over the voices of Times Square’s users.28 But the show certainly enabled the assessment of precarity in an area threatened by imminent change, in debacle-bound New York. The building’s four floors (including ground level) were fully invaded. Amassed on top of each other in varying thicknesses, all media mixed, the works proliferated from cellar to attic, devouring the most incongruous of places, including the restroom (Joe Fyte, Becky Howland)29 and staircase (Jane Dickson and Jody Culkin, Kiki Smith, Mike Glier, etc.). They appeared in the nooks where one normally finds only dust; one would brush against them in narrow hallways or in the cubicles that bore witness to the local sexual architecture (Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf). In fact, this show ‘of’ Times Square was an attack on the methods – laundering and neutralization – usually employed by museums and galleries to separate artworks from the contagion of the world.

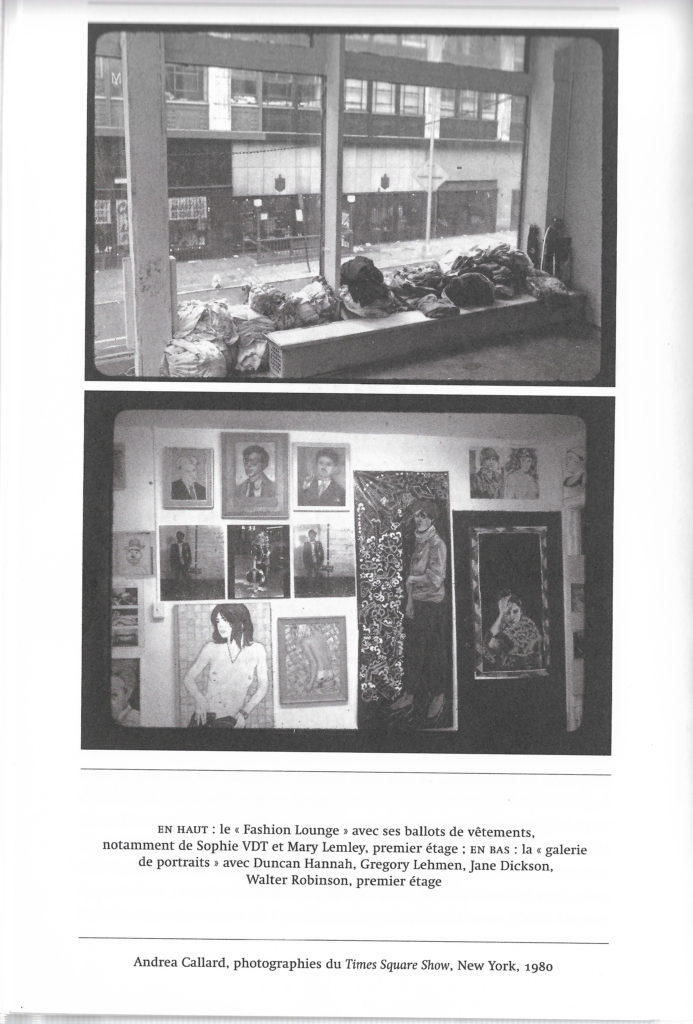

This old ruined building had nothing to do with the lofts converted into galleries which had by then overtaken SoHo, from where artists, little by little, were being removed. The plaster crackled. Graffiti showed signs of indeterminate age. The first-floor windows had been dismantled. This was a way of opening the exhibition to the sounds of the street. Boomboxes, voices, and cars blended in with tunes from a juke-box, the words of peddlers, the music of carnival (Bobby C) and the throat sounds of a puppet imitating James Brown. Connected to a record player, the puppet served as the building’s doorman. Light from outside penetrated generously, sometimes filtered in red. Outside: a display of the building’s plan drawings (Tom Otterness), graffiti (Fred ‘Fabulous Five Freddy’ Braithwaite), and a frieze made up of emblems taken from advertisement and recomposed with the familiar commercial signage. Jean-Michel Basquiat had spray-painted ‘Free Sex’ onto the door, but the inscription was removed – on the pretext that there was, in fact, no free sex in this massage parlor. The signage for the exhibition was a series of painted boards hanging from the first-floor windows, boasting the attractions supposedly available inside: hand-painted portraits and a painted grotto, ‘thrift shop, sex machines, business advice, real mermaid, and accidental death’.30 Over a hundred artists participated in the project; the vast array of pieces imposed a compacted display that left no room for the isolation of artworks. One always saw many things at once; sometimes, one collided with them. Works intruded on the spectator’s space just as the spectacle of the street infiltrated the space of the works.

Image 6

Image 6

The show’s conditions of existence, as well as many of the materials used by the artists (plaster, plastic, industrial waste, cardboard, papier-mâché, photocopy) made the objects vulnerable to the attacks of time and excessive manipulation. The lifetime of artistic objects only barely exceeded that of their perception. Thus, the event merged with the process of urban alteration itself. Many of the exhibited works – especially those by female artists – were committed to evoking the site’s former destiny: sex work and industry, whether applied to domestic life (Jane Dickson), or not. A waitress’s sexual exploitation is described in detail; allusions to sadomasochism proliferate, sometimes manifesting through explicit photography (Jimmy De Sana and Mike Glier). Leather, steel, and rope are the materials in vogue. But the artists’ interest in S&M seems to be a cover, used to express their ambiguous feelings towards institutions.

The building’s larger rooms were like multiple private salons: the one somewhat melodramatically named ‘Money, Love and Death’ housed a tight display of paintings, statues and drawings against the background of a patterned wallpaper titled Gun, Dollar, Plate (Coleen Fitzgibbon and Robin Winters). A ‘Portrait Gallery’ brought together anonymous individuals and the high dignitaries of the ‘phallocracy’ (Caz Porter and Janet Stein). It was as if The Great White Way (Joe Lewis) must always be disowned, as if the show’s austere abstract ‘black paintings’ (Olivier Mosset) must always be associated with the shambles of an ‘open-air fashion fair’. These stark contrasts among the works revealed a desire to rectify the existing idea of this New York new wave as a white, bourgeois movement. Even though this was in fact the case. Yet at the same time, the movement succeeded in securing the alliance and participation of black and Latino artists,31 who had too often been confined to categories of ‘ethnic’ art to which the institutional world remained closed. Some of these works further disrupted the affects of racism. A sculpted pantheon (John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres) was thus dedicated to the inhabitants of the South Bronx, then New York’s most dilapidated neighborhood. The monument’s plaster busts had been molded publicly beforehand, on the street. The Black Panthers were commemorated too (Candace Hill-Montgomery), and a ‘war room’ was dedicated to the urban guerilla and border issues in the Middle East (Peter Fend). The living conditions of vast homeless populations were explored, while half-burnt photographs of abandoned ruined buildings in the South Bronx were placed in bottles (Marc Blane).

Art was playing with the risks and the detritus of consumption in urban environments. David Hammons recycled bottles of cheap wine found on the streets by breaking them against the staircase, which was so narrow that passersby were at constant risk of stumbling. Inviting the crowds of the city’s undergrounds to emerge in the exhibition, Christy Rupp built a real fountain made of false rats perched on beer cans. It was surrounded by growing waste, produced both by the artist and the visitors. The figure of the rat, repeated on sheets of paper placed anywhere an empty space appeared, roamed the floors of the Times Square Show. With Rat Patrol (as the work was called), the animal cruised seamlessly outside and in, since rats know none of these borders. A well of oil resting on two dollar-bags functioned as a flush, spreading a concoction that smelled of gasoline into a public urinal (Becky Howland). Stalls taken from Canal Street, where merchandise was sold at knocked-down prices, were used to display a pharmacy of vaguely expired drugs and pills (Bobby G.). On the side of 7th Street, known as Fashion Avenue (the heart of the garment district), a collective shop was installed, where shabby shelves displayed piles of clothes, erratically enhanced by layers of paint (Mary Lemley, Sophie VDT, Paul Greif, Karen Lunar, Ester Balint, Vicki Pederson). A fashion show, on the theme of white, brought the exhibition to a close. Cleaning and laundering (in French blanchiment, literally ‘whitening’) paradoxically became a signal for the end of hostilities through aesthetization.

In the meantime, most of the show’s fervent organizers and viewers (including myself) were beginning to set up camp on site. A surviving poster informs me retroactively of the artists’ performances32 and films33 programmed over the weekends, coupled with political documentaries and cult movies like Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour (1950). Nan Goldin showed her slide-show travelogue (Ballad of Sexual Dependency), John Ahearn and Jim Jarmusch, their films. The calendar becomes vaguer when it comes to Jack Smith, the veiled hero in a Hamlet costume, captured in one of the hilarious trailers produced for the exhibition. His presence, scheduled from Friday midnight until late Saturday night, caused a riot within a few square meters. In them, he performed Exotic Landlordism of the World, one of those projects he had been fomenting for almost twenty years and which, one day, would be named Normal Love. ‘Since “Flaming Creatures”, I’ve been involved in a working method that might be called “LIVE FILM.” Some of the work goes on through the screening itself. Someday, this might be imitated for there is almost no other way to dislodge film out of the bankrupt state it is now in which can only be goosed up by more and more violence and synchronized chatter.’34 His company, adorned with caftans and turbans, answered to the name of Sinbad Glick & the Brassiere Girls of Bagdad. He had formed it in an Orientalist craze of some sort, together with two prostitutes from the neighborhood and a multitude of available objects – an adventure through the texture of slides. ‘Jack Smith lights a bunch of incense and his veil catches on fire. The belly dancer helps put it out. A guy wearing ripped pantyhose, binocular-shaped false boobs and leather boots falls down the steps to join them. Nothing really happens, just a lot of bumbling. Jack Smith smokes a pipe of dope or something, holds up an empty beer can, shakes it, strokes it (hoping for a genie?), picks up an overloaded extension cord and pronounces it “the Octopus of Atlantis.” He asks “Sinbad” (the Brassiere Boy) to read a story – “Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves” – aloud from a children’s picture book. The guy does so in a flat, fast monotone’. This is how the Soho News tells it. It did not appeal to people then. But posterity praised to the skies this materiality that ‘infects time’, which director Richard Foreman described as a witness to ‘human behavior turn[ed] into granular stasis, in which every moment of being seemed, somehow, to contain the seed of unthinkable possibility’.35 In its relentless resistence to the temporal economy of cultural productions, Smith’s obsessive hostility towards the capitalism of exploitative landlords began to spread.36 Fully immersed in the world of the exploited, the Times Square Show replicated it on the scale of an exhibition. Through it, the conflicting affects linked to the aggressive circulation of capital reverberated and spread.

This mode of intervention – the impregnation, indeed the contamination between context and project – was precisely how the artist cooperative Colab (Collaborative Projects) had decided to work. The group was formed in 1977 as a reaction to the ways in which public and private funds were being distributed to artists via intermediary bodies.37 About sixty artists ‘concerned with conceptual ideas and the political figurative in art’ composed Colab,38 but not without conflict. These artists had split the task, first of obtaining, then of organizing the building of the Times Square Show, dividing into groups of two or three per floor. They were finally in charge of communication for the exhibition, which was handled through collectively made satirical films.

Image 7

Image 7

Image 8

Image 8

Image 9

Image 9

Image 10

Image 10

The issue of real estate opened the 1980s and was further broached by another exhibition, the Real Estate Show. Organized by a Colab collective,39 it was intended as a communal realization of ‘the way money controls where and how people live in New York City’,40 property speculation, and the demographic shifts triggered by the latter in traditionally poor neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side. ‘Real estate is not about people living or working somewhere. Actual real estate, both private and public, means buying, financing, subdividing, renting, selling, demolishing, mortgaging, constructing, for profit.’41 Opposed to this pattern, these artists questioned the ‘old conception of the creative artist realizing his aim of freedom through contemplation of art pieces’.42 Hence the curatorial dynamics that would give shape to this discourse had also aimed to be open, process-based, egalitarian, and without any limitations regarding the space dedicated to each work. A little while before the Real Estate Show opening, and following several scouting missions, more than thirty artists entered a municipal building, which had been abandoned for over two years, on 125 Delancey Street near the Williamsburg Bridge. Together, they cleaned, repaired the plumbing, built in a heating system – it was the end of December – and installed their works. Unrestrained by medium, they addressed methods and usages, acts of arson brutally perpetrated to dislodge residents, and made proposals for viable alternative energies. We spent the night of December 31st 1979 there. The exhibition lasted exactly one day. We discussed speculation, the rights of tenants, abuse, real-estate undertakings, the arbitrariness of urban planning. On January 2nd 1980, seals were affixed to the doors. On January 11th, the police seized the works.

A press conference, in the presence of Hans Haacke and Joseph Beuys, ensued from the seizure. Following negotiations, Colab was given permission to use a storefront on Rivington Street, which became an exhibition space under the name of ABC No Rio.

As the art historian Miwon Kwon writes fiercely, ‘certainly, site-specific art can lead to the unearthing of repressed histories, provide support for greater visibility of marginalized groups and issues, and initiate the re(dis)covery of “minor” places so far ignored by the dominant culture. But inasmuch as the current socioeconomic order thrives on the (artificial) production and (mass) consumption of difference (for difference’s sake), the situation of art in “real” places can also be a means to extract the social and historical dimensions out of places.’43 Thus, while it reinvigorated the old model of artist salons, the Times Square Show could not escape the hold of an art market which has the capacity to absorb the works that parody it. This same market also takes on the careers of artists who, in this case, did not all resist for very long the temptation of exhibiting in the very spaces that the show had seemed to castigate. In this turn of events, artist and critic Walter Robinson even sees a critical juncture, where the East Village scene was about to become a ‘mockery’, a professional refuge for the art world that went there to find its place before occupying the premises.44 As for the site of Times Square, it was, more than any other, the laboratory of a renovation politics aiming to change a ‘shameful’ neighborhood into a more respectable district. The rise of panic linked to the AIDS epidemic supplied the setting for a discourse that could request the general ‘disinfection’ of the city.

A few months after the Times Square Show, collaborative galleries opened in the East Village. ABC No Rio, whose name was borrowed from an old street sign, declared from the start on its May 1st inaugural celebration that it wished to be a bridge between artists and the local working-class population. Christy Rupp explained to me then: ‘We were put here for free because we were an organization of white artists – to reassure people and assure them that they could move into the neighborhood. But we are trying to use the space to bring in communities and allow them to participate’. ‘It’s easy to get the press, but harder to get the neighborhood folk. We’re a façade but our aim is the opposite. At a minimum, it is about documenting the area’s disintegration; at best, it is about raising consciousness about the consequences of a renovation.’45 In addition to new spaces such as Fashion Moda in the South Bronx (which would become one of the platforms for hip hop and graffiti art), or El Taller Boricua (a group of Puerto Rican artists started in the 1970s to serve the Puerto Rican community), collectives multiplied: PAD or PADD (Political Art Documentation/Distribution), CUD (Contemporary Urbicultural Documentation), and soon the gallery Exit Art.46 In October 1980, a front window on 244 East 13th Street opened under the name Group Material. This collective of New-York artists was mainly made up of former students of the School of Visual Arts grouped around conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth, as well as former students of the University of Maine at Augusta and of the AMCC, the movement of artists for cultural change,47 plus friends and friends of friends.48 More than the production of objects, this heterogeneous collective was motivated by the necessity to pursue conversations and practices that would hold together through shared ground – not a space, but a place, our own laboratory – painted, not in white-as-in-white-cube, but in grey and red.

Rising here was a ‘movement’,49 one that sought to rethink the interactions between exhibitions, objects, and context. And production involved a movement of collecting, ‘in which multiple points of view are represented in a variety of styles and methods’,50 mobilizing a community of users. Everyone joined in the conversation with varying expectations, objectives, and appreciations. The arguments and quarrels of sometimes irreconcilable differences in ideology or personality led to declaring: ‘dissensus is an emotional invention of great beauty’.51 Alienation, consumption, elections, gender, food, enthusiasm: keywords turned into an ensemble of artifacts in a scenography. Invited to the 1985 Whitney Biennial, Group Material flooded the museum’s ground floor. Under the spotlight of theater lamps, in a décor of wallpaper strips over Marcel Breuer’s original architecture, the scenography of Americana was conceived like a (photo)montage. It created radical interactions between Reagan-era consumer items (a TV monitor turned-on, two washing machines, detergent) and the works of artists neglected by the institutions and aiming all their critical potential at American culture. Americana proposed a deconstruction of curatorial norms and their excluding practices – a strategy which the group’s Kafkaesque The Castle would repeat at Kassel’s documenta VIII in 1987. Other techniques of spatial distribution, borrowed from the world of political activism, were also explored: poster campaigns, inserts, the production of bags, the writing of timelines.52 Thus, the narrative about the 88 interventions by the US government in Central and Latin America since 1893 was publicly reproduced via a timeline at P.S.1 in 1984 in the work Timeline: The Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America. This presentation technology of historical time allows one to revisit contemporaneity in a critical way, by splitting the times of production and reception of artworks: Diego Rivera suddenly becomes associated with the 1980s and John Heartfield with the nineteenth century.

In 1988, Group Material, whose work had already occupied the Dia Art Foundation several times, proposed four ‘subjects for democracy’ over four months in the institution.53 Education, Cultural Participation, and Politics and Election constituted the first three. The fourth part was dedicated to a case study: AIDS and Democracy (December 1988-January 1989). It was dedicated to William Olander, the New Museum senior curator who had author(iz)ed the first spectacular museum gesture in the struggle against AIDS, namely the installation Let The Record Show in the museum’s main window on Broadway in Lower Manhattan (1987). Under a version of the slogan SILENCE=DEATH in pink neon, the piece included a large photomural of the Nuremberg trials. In front of it stood alternately lit cardboard cutouts of six public figures, five of which were held accountable for their statements written on a plinth beneath them, and the sixth, President Reagan, accused for his notorious silence on the AIDS crisis. Below the neon sign, a LED sign displayed running text on statistics, government inaction, and elaborations on the defendants’ records.54 At the time of Group Material’s opening, Olander was very ill. A ramp was built, allowing him to access Dia’s 77 Wooster Street space with a wheelchair. Various emotions, such as ‘sorrow, rage and fear’, largely uncalled for or unwelcomed in traditional militant discussions, emerged within commitment to shared goals fostered by collectives such as ACT UP and WHAM (a collective for women’s health). These collectives were made active in the installation, through printed matter and looped videos. Political emotions collided with artworks. The colorful works up on the walls were contaminated by concrete data about AIDS, and reciprocally. One had to face them both, in solidarity. No one emerges unscathed. In other words, it was also about exposing the institution’s works (by Gretchen Bender, Ross Bleckner, Louise Lawler or Jannis Kounellis) to information about AIDS and, thus, to affect them. As Elizabeth Hess explained, although some predated the epidemic (a 1942 photograph by Dorothea Lange, for example), the exhibition conveyed a particular significance to the works already on display.55 Part of the installation AIDS & Democracy. A Case Study was presented in 1989 at the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (nGbK) in Berlin, in the context of the show Vollbild AIDS. Eine Ausstellung über Leben und Sterben.56 Organized by the activist-curator Frank Wagner, it was the first exhibition dedicated to AIDS curated in Europe.

Group Material had become involved in the AIDS Timeline at the invitation of Lawrence Rinder, curator at the Matrix gallery of the Berkeley University Art Museum, which would house the first iteration of the work at the end of 1989. A black vinyl band, running horizontally around the gallery with data and charts documenting the AIDS-related ‘line of time’ of the 1979-89 decade, was compiled with the help art historian Richard Meyer, then a doctoral student at the University.57 The band was interspersed with objects, artifacts, texts and media, turning the exhibition into a powerful critique of institutional heteronormative delineations of historical time. It achieved this first (but not most), by using ephemera as evidence, displaying compiled data and documents – posters, stickers, flyers, magazine articles and covers – in the similarly ephemeral field of the exhibition, where ‘facts’ are provisional. AIDS Timeline is at once an installation, an exhibition, and a 3D ‘montage’ in the cinematographic sense of the term. It is also a (counter)-historical synoptic tableau, in which the dateline numerals are displayed in reverse order to customary Western reading, with years regressing instead of progressing. In such a representation, a certain rhythm is turned in on itself: time runs, time is running out. For individuals living with HIV/AIDS, time is not only counted and compressed, it also holds the potential for the intensification of the present tense.

In this inclusive show, artworks and artifacts (two ACT UP ‘SILENCE=DEATH’ T-shirts displayed on two hangers), photocopies of newspapers, paintings, texts, masks, photographs, flyers, brochures, typography, and quotes constitute the material for a tridimensional experiment. Data, design, and objects suggested altogether that ‘AIDS has been constructed through both a bio-medical discourse of infection, incubation, and transmission as well as the cultural vocabulary of innocence and guilt, dominance and deviance, threat and threatened, self and other’.58 In other words, the timeline translates the extent to which mainstream discourse and dominant media partake in, or rather construct, the materiality of the AIDS epidemic. Next to the year 1985, one reads: ‘In late July Rock Hudson discloses that he is ill as a result of AIDS. President Reagan, who has never said the word AIDS in public, calls to wish Hudson well. The American media quadruples its coverage of the syndrome’. The AIDS Timeline goes on ‘to expose, to show, to demonstrate, to inform, to offer’ an epidemic of representation. Three charts are dedicated to tracing the ‘demo-graphics’ formed by HIV-positive diagnosed Americans, deaths caused by AIDS, and governmental resources provided for AIDS-related research. Equally significant are the memories of the disco anthems displayed by title for each year (selected by Stevan Evans: High Energy in 1984; Sylvester’s Take Me to Heaven/Sex in 1985; Never Can Say Goodbye in 1988…). The AIDS Timeline monopolizes the queer pop culture that developed from the mobilization against the epidemic. Darth Vader’s figure from The Empire Strikes Back (1980) is juxtaposed to a photograph of Reagan taken during his presidential inauguration. And the promiscuity of certain works is contagious. Intimacy and remoteness are ‘locked in symbiosis’, according to the words of Felix Gonzalez Torres, member of Group Material. Certain contributions function through reactivation: Nancy Spero’s embroidered feminist slogan of 1970, for instance. ‘This womb does not belong to doctors, legislators, judges, priests, the state, etc.’ In 1986, it was projected onto Times Square’s electronic billboard. This Womb Does Not Belong to Lawyers has reappeared on paper, as part of an advertising insert for the May 22, 1988 Sunday edition of New York Times, during Group Material’s Democracy Project at the Dia Art Foundation. The work’s journey resonates critically in the AIDS Timeline. In return, being placed in the exhibition’s context affected the materiality of the works on display. In Michael Jenkins’ American-flag painting June 30, 1986 of 1988, the voided rectangle is stripped down to nine stripes, and a blank space marks the absent field of stars. Hanging downwards, mimicking a Daniel Buren stripe painting, June 30, 1986 is situated according to its date-title. Indeed on June 30th, 1986, the nine Supreme Court judges made one of the most far-reaching decisions concerning LGBT rights in the United States. Known as ‘Bowers v Hardwick’, the decision upheld the constitutionality of Georgia’s sodomy law, condemning sexual activity between people of the same sex. Next to the date 1979, Nayland Blake placed a vitrine made in 1989. In it, five different softcover editions of Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock (1970) are chained together, constituting a retrospective of the early days of the epidemic, or at least a version of it. A history ‘projected backwards from 1989 […] by which point the crisis had fully metastatized, and forward as though proleptically from 1970…’.59 This careful game of re-situating objects is not dissimilar to a chessboard, which art historian Hubert Damisch used as a metaphor to describe exhibitions concerned with history. ‘On a chessboard, one can play different types of games, not only chess. […] What does it mean? It means that in order to acquire a sense of history, one has to refer to a delimited space, in which history is to take place’.60

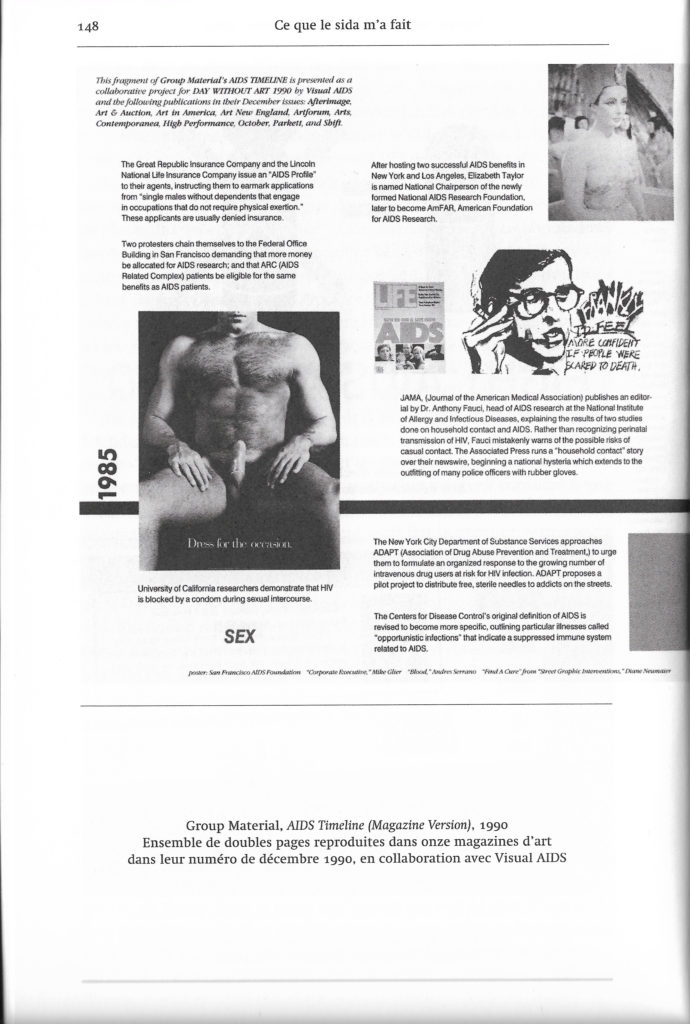

In its first version at Berkeley, the exhibition had been contextualized for the here and now of the Bay Area, namely a moment and place massively affected by HIV and AIDS. Blue and gold signs inside the museum invited the university community to fill in a questionnaire, which tackled individual consciousness: How does AIDS affect you as a person, your lifestyle? The show was aimed at local action: a series of videos, in the university’s sports facilities, offered forms of homoeroticism as resistance to the phobia of AIDS. A full page of The Daily Californian was handed over to Gran Fury, ACT UP’s sister graphic collective. On December 1st, 1990, the date of World AIDS Day which was designated as ‘Day Without Art’ by the organization Visual AIDS, Group Material’s Timeline was turned into printed matter. In order to challenge a totalizing and synoptic reading, it was cut up in double-page fragments published separately in eleven art magazines,61 which came together as a community to disseminate the work. Likewise, for each of its reconfigurations – in 1990 at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Hartford or in 1991 at the Whitney Biennial – the work was updated. And Group Material itself was transformed as a collective. It became a ‘collaborative’ body. By preserving everything, down to the last piece of paper, by combining personal notes and meeting minutes, applying no more hierarchy among registers than among their respective media, the creation of the group’s archives became a creative project, which Julie Ault undertook following the group’s dissolution in 1996. Today, another form of the AIDS Timeline as an archive is available at NYU’s Fales Library, within the ‘Downtown Collection’, and includes the leftovers from its different displays.

AIDS Timeline is a major marker of what AIDS did to exhibitions. It is the place where the aesthetic regime of exhibiting was contaminated by the activist discourse produced by the graphic and videographic activities of groups struggling against AIDS. And as with any exhibition, AIDS Timeline had also necessitated prior research, the procurement and collection of documents and artifacts – posters, magazines, photographs, stickers, trinkets – including those arising from the collectives that were part of the endeavor (ACT UP, Gran Fury, GANG, etc.). AIDS Timeline thus devised a stock of quotations – verbal, visual, musical, emotional – that ‘replayed’ and rerouted the historical form of conceptual art exhibitions. AIDS unsettled the relationship between ‘doctor’ and ‘patient’. Indeed the Denver Principles in 1983 were initiated with the declaration: ‘We condemn attempts to label us as “victims,” a term which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally “patients,” a term which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are “People With AIDS”. Similarly, Group Material unsettled the relationship between the institution and its memory. From early on, they explicitly referred to Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne, and to André Malraux’s Imaginary Museum, in the spirit of countering conventional forms of art collection and distribution. It is significant that this event took place at a museum in 1989, while the fall of the Berlin Wall was proving the inability of grand narratives to organize the world. AIDS Timeline stirred the relationship between ‘facts and figures’, declining both the supposed objectivity of facts and the constrained subjectivity of figures. By endlessly cementing this polarity, these groups were also endlessly questioning it, through forms of collective representation and the production of public space, namely the kind of history that is written by exhibitions.

TRANSLATION OF THE IMAGE CAPTIONS

All scanned pages are excerpted from Ce que le sida m’a fait, published by JRP Ringier and La maison rouge in 2017.

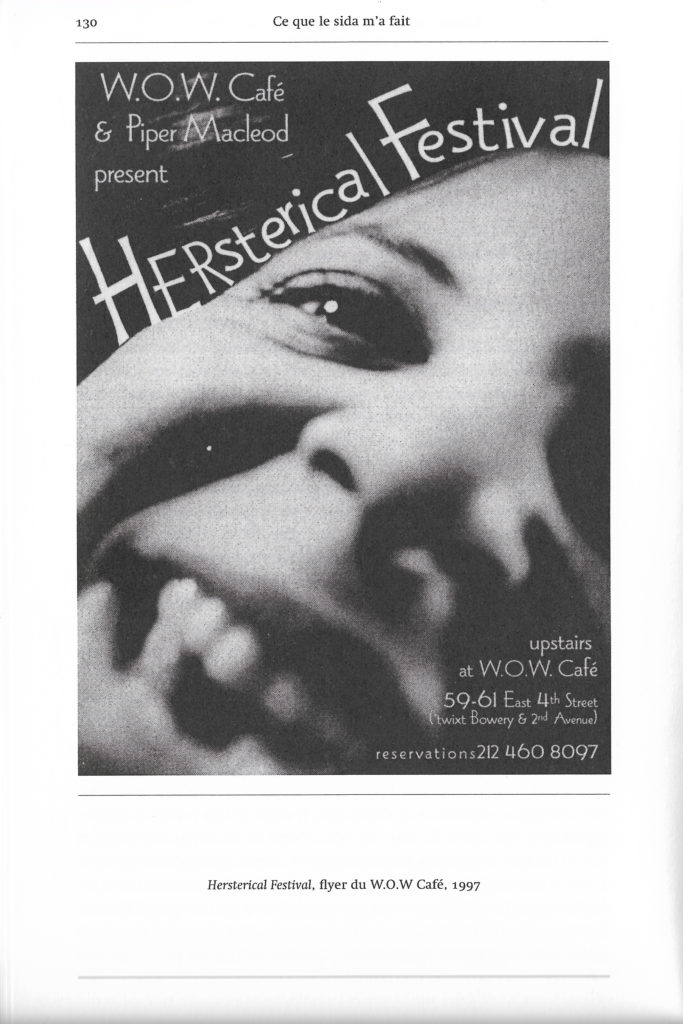

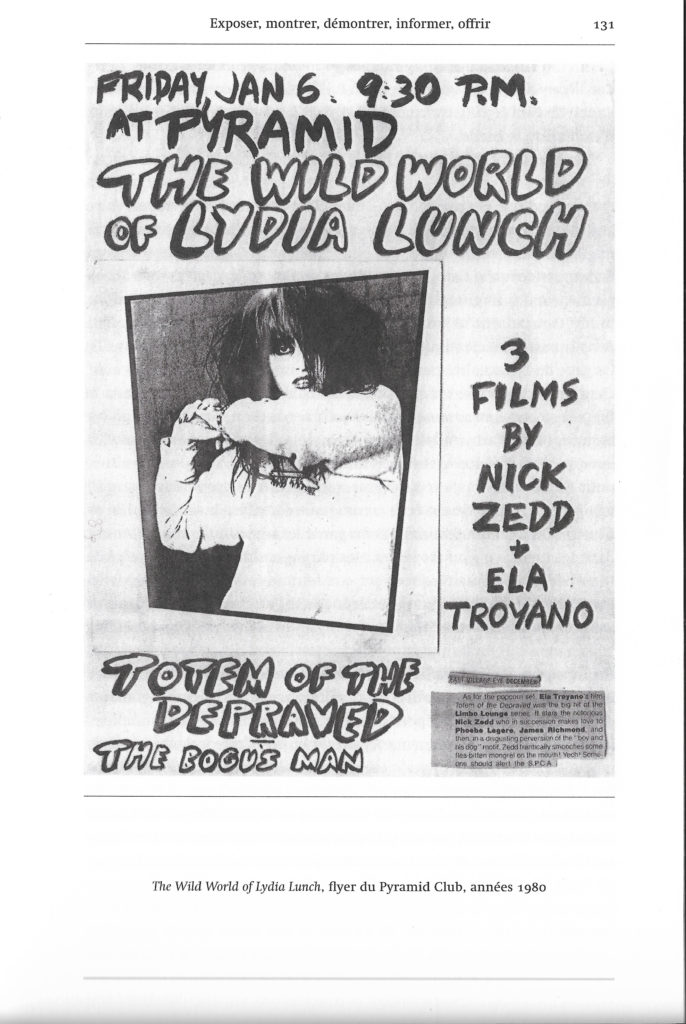

Images 1-2. Hersterical Festival, W.O.W. Café flyer, 1997. The Wild World of Lydia Lunch, Pyramid Club flyer, 1980s.

Image 3. Flyers for the Times Square Show, 1980.

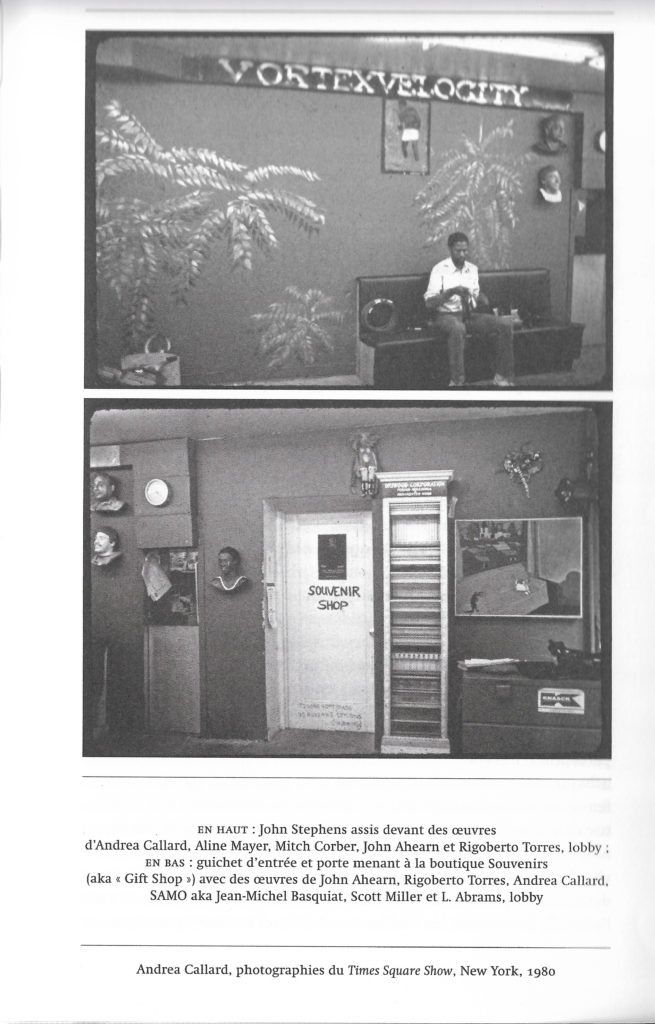

Images 4-5. ABOVE: the ‘Fashion Lounge’ and its bundles of clothes, notably by Sophie VDT and Mary Lemley, first floor; BELOW: the ‘portrait gallery’ with Duncan Hannah, Gregory Lehmen, Jane Dickson, Walter Robinson, first floor. ABOVE: John Stephens, sitting in front of the works of Andrea Callard, Aline Mayer, Mitch Corber, John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, lobby; BELOW: ticket office and door leading to the ‘Gift Shop’ with works by John Ahearn, Rigoberto Torres, Andrea Callard, SAMO aka Jean-Michel Basquiat, Scott Miller and L. Abrams, lobby. All images: Andrea Callard, photographs of the Times Square Show, New York, 1980.

Image 6. ABOVE: Keith Haring, invitation flyer to his exhibition New Drawings, ‘Des Refusés’, Westbeth Painters Space, New York, 1981; BELOW: Jack Smith, business card, 1981.

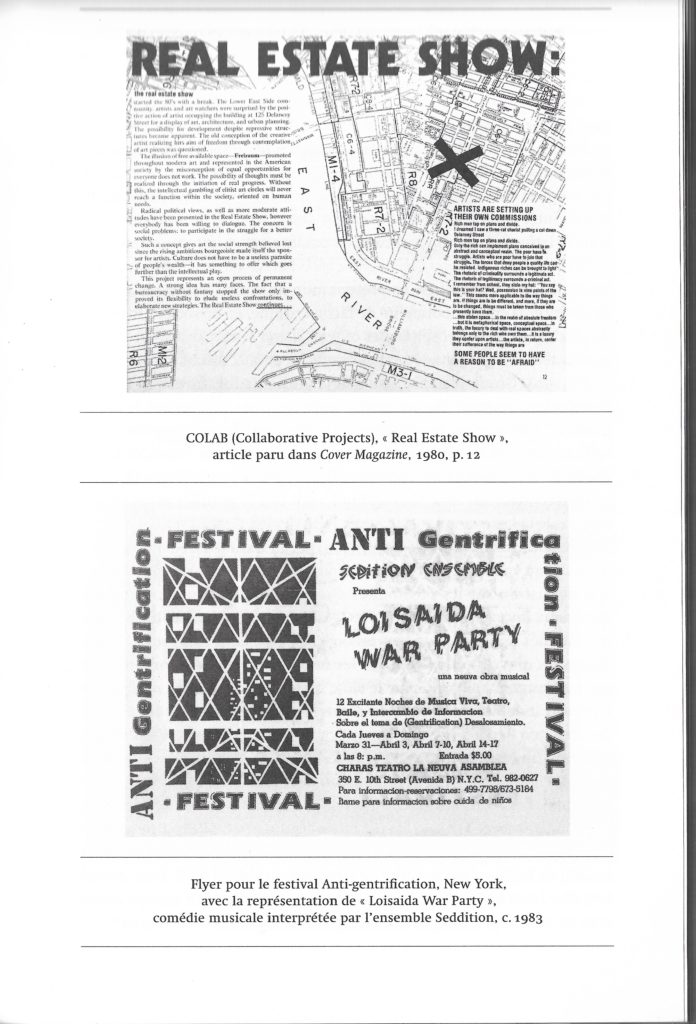

Image 7. ABOVE: Colab, ‘Real Estate Show’, 1980, article published in Cover Magazine, p.12; BELOW: Flyer for the Anti-gentrification festival, and Loisaida War Party musical comedy, interpreted by the Seddition ensemble, c. 1983, New York.

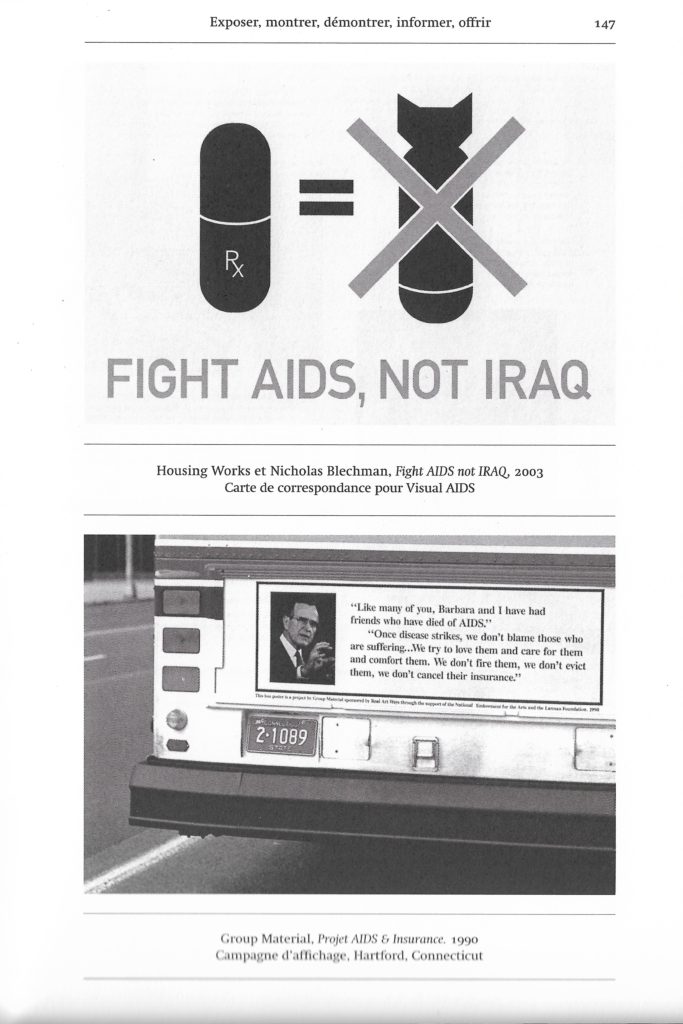

Image 8. ABOVE: Housing Works and Nicholas Blechman, Fight AIDS not IRAQ, 2003, Visual AIDS compliment slip; BELOW: Group Material, Project AIDS & Insurance, 1990, poster campaign, Hartford, Connecticut.

Image 9. Group Material, AIDS Timeline (Magazine Version), 1990, series of double pages reproduced in eleven art magazines in their December 1990 issues, in collaboration with Visual AIDS. Here: the year ‘1985-1986’ published in Artforum 4 (1990).

Image 10. Group Material, AIDS Timeline (Magazine Version), 1990, series of double pages reproduced in eleven art magazines in their December 1990 issues, in collaboration with Visual AIDS. Here: the year ‘1990’ published in Parkett 26 (1990).

1 This text was adapted from L’Argent dans le discours des artistes américains, 1980-1981, doctoral thesis supervised by Gilbert Lascault, Université Paris-X, Paris, 1983. The new title is borrowed – and was originally translated into French as Exposer, montrer, démontrer, informer, offrir – from an eponymous exhibition and catalogue (edited by Matthias Michalka) at MUMOK, Vienna, in 2015, addressing art practices from around 1990.

2 Kathy Acker (1978) Blood and Guts in High School (London: Penguin Classics, 2017).

3 Concerning the gentrification of the East Village, see Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan, ‘The Fine Art of Gentrification,’ October 31 (1984): 91-111.

4 Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2012), 76.

5 Lewis Munford, The Culture of Cities [1937] (New York: Harvest Books, 1970), 4.

6 Published in 1988 by Twelvetrees Press; republished in 2014 by Steidl.

7 See Janet L. Abu-Lughod, ed., From Urban Village to East Village: The Battle for New York’s Lower East Side (Cambridge: Wiley-Blackwell, 1995) and John Brigham and Diana R. Gordon, ‘Law in Politics: Struggles over Property and Public Space on New York City’s Lower East Side,’ Law & Social Inquiry 21:2 (1996): 265-83.

8 The summer of 1988 was particularly violent. See Clayton Patterson, ed., Resistance: A Radical Political and Social History of the Lower East Side (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2006).

9 See Lionel Rogosin’s beautiful film On the Bowery (1957).

10 In English in the original text.

11 Robert Smithson, Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1986), 380.

12 See Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune. (London and New York: Verso, 2015)

13 Peggy Phelan, ‘Spatial Envy: Yvonne Rainer’s The Man Who Envied Women,’ in Unmarked. The Politics of Performance (London: Routledge, 1993), 80.

14 Rashidah Ismaili-Abubakr, ‘Slightly Auto-biographical: The 1960s on the Lower East Side,’ African American Review 27:4 (1993): 585-92.

15 Miguel Piñero, ‘A Lower East Side Poem,’ in Herencia: The Anthology of Hispanic Literature of the United States (Oxford: The Oxford University Press, 2002), 239.41.

16 The thousands of objects and ephemera accumulated by Martin Wong were the subject of the exhibition I M U U R 2, organized in 2013 at the New York Guggenheim by the artist Danh Vo. The eponymous publication (Berlin: Galerie Daniel Buchholz, 2013) included texts by Julie Ault, Heinz Peter Knes, Danh Vo, and Martin Wong.

17 Juan A. Suárez, ‘The Puerto Rican Lower East Side and the Queer Underground,’ Grey Room 32 (2008): 6-37.

18 See Alan Moore and Jim Cornwell, ‘Local History: The Art of Battle for Bohemia,’ in Alternative Art New York. 1965-1985, ed. Julie Ault (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

19 See François Peraldi, ed., ‘Polysexuality,’ Semiotext(e) (1981).

20 Sylvère Lotringer, ed., ‘Schizo-Culture,’ Semiotext(e) 2 (1978) This issue came out three years after an ‘event’ at Columbia, in which Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Jean-François Lyotard shared the stage with William Burroughs, Kathy Acker, Richard Foreman, John Giorno, and John Cage.

21 Peraldi, Polysexuality.

22 Sarah Schulman, ‘When We Were Very Young: A Walking Tour through Radical Jewish Women’s History on the Lower East Side 1879-1919,’ in My American History: Lesbian and Gay Life During the Reagan/Bush Years (New York: Routledge, 1994), 136.

23 Jennifer Doyle, Hold it Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 128.

24 Ibidem.

25 Eileen Myles, ‘Hot Night,’ in Not Me (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991).

26 This was my first text, which I had written for Libération but never sent to the editors. Thus I recycled it into my doctoral thesis, borrowing one of the artworks, a gouache on photocopy by Robert Goldman (Money Talks, 1980), to reproduce it on my cover. The pages that follow are an almost faithful transcript of this first text.

27 See Samuel Anderson, ‘Inherent Vice: Contagion and The Archive in The Times Square Show,’ accessed http://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/e-misferica-61/s-anderson/.

28 See Lucy Lippard, ‘Sex and Death and Shock and Schlock: A Long Review of The Times Square Show by Anne Ominous,’ in Postmodern Perspectives: Issues in Contemporary Art, ed. Howard Risatti (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1990), 77-86.

29 Names are given on an indicative basis. For more details, see the plans drawn by John Ahearn and Tom Otterness: Times Square Show Floor Plans, 1980. Accessible at http://www.timessquareshowrevisited.com/.

30 See Anderson, ‘Inherent Vice’.

31 Many of them come from Bronx’s Fashion Moda, managed by Joe Lewis and Stefan Eins, both also members of

Colab (Collaborative Projects).

32 Illona Granet : Rape, Ravage and Roll Utopia, Or Else ; Gary Indiana : Psychic Plague, Michael Smith…

33 Films by Scott and Beth B, James Nares, Betsy Suller, Michael Oblowitz, Stuart Sherman, Dara Birnbaum, etc.

34 Jack Smith in Wait for Me at the Bottom of the Pool: The Writings of Jack Smith, ed. J. Hoberman and Edward Leffingwell (New York: Serpent’s Tail, 1997), 149.

35 Quotes from the Village Voice (1980) by the artist Nayland Blake and the director and playwright Richard Foreman are from Anderson, ‘Inherent Vice’.

36 Marc Siegel, one of Jack Smith’s most fervent exegetes, mentions Exotic Landlordism (1964-9), Song for Rent (1969), Boiled Lobster of Lucky Landlady Lagoon (1969-72), Spiritual Oasis of Lucky Landlord Paradise (1969-70), and Irrational Landlordism of Bagdad (1977).

37 Among Colab’s projects that received funding (other than the artists’ own contributions) were the ABC No Rio space, the Real Estate Show and Times Square Show (1980), the New Cinema, the cable shows Potato Wolf, All Color News and Red Curtain, the publications NightShift Theater, X Motion Picture Magazine, Tellus Audio Cassette Magazine, the gallery Fashion Moda, and the A. Moore Store.

38 Coleen Fitzgibbon’s account, http://www.timessquareshowrevisited.com/.

39 To which Becky Howland, Alan Moore, Peter Mönning, Edit De Ak, Anne Messner, and Peter Fend belonged.

40 Lehmann Weichselbaum, ‘The Real Estate Show,’ The East Village Eye (February 1980): 8-9.

41 Bethany Haye, ‘The Real Estate Show,’ The East Village Eye (February 1980).

42 Unsigned announcement, Cover Magazine (Spring/Summer 1980).

43 Miwon Kwon, ‘One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity,’ October 80 (Spring 1997): 85-110.

44 See also Craig Owens, who compares the East Village to a ‘junior’ model for the cultural industry. Owens, ‘The Problem with Puerilism,’ Art in America 72 (Summer 1984): 163.

45 Christy Rupp, interviewed during my doctoral research. In 1979, Beni Matias and Marci Reaven documented the issues of ‘our’ housing and ‘our’ Puerto Rican community in The Heart of Loisaida.

46 For a full panorama of these artistic genealogies, see Ault’s indispensable Alternative Art New York (full reference above).

47 A movement in which critic Lucy Lippard and artists Kosuth, Nancy Spero and Leon Golub campaigned.

48 They were Hannah Alderfer, George Ault, Julie Ault, Patrick Brennan, Liliana Dones, Anne Drillick, Yolanda Hawkins, Beth Jaker, Mundy McLaughlin, Marybeth Nelson, Marek Pakulski, Tim Rollins, Peter Szykpula, Michale Udvardy. In 1980, departures were recorded: Pakulski, followed by Drillick, Alderfer, Jaker, Nelson and other members of Group Material, reduced to three members by 1981! Doug Ashford joined the collective in 1982, followed by Felix Gonzalez-Torres; and Tim Rollins left it in 1987 to focus on his pedagogical project KOS, Kids of Survival, as he felt the presence of Gonzalez-Torres would secure the collective’s continuity. Karen Ramspacher, anti-AIDS activist and assistant curator at Dia, joined the group in 1989. See Ault, ed. Show and Tell: A Chronicle of Group Material (London: Four Corners, 2010).

49 See Julie Ault, http://www.as-ap.org/oralhistories/interviews/interview-julie-ault-founding-member-group-material.

50 Group Material, Democracy: A Project by Group Material

51 According to Doug Ashford. See Jonathan Griffin, ‘Arroz con Mango (What a Mess): Group Material,’ Mousse Magazine 23 (2010).

52 DA ZI BAO, Union Square, New York, 1982; Subculture, New York subway, 1983; Inserts in the New York Times, 1988; MASS, kit project ready to be exhibited, 1985-86; Shopping Bags, Hamburg, 1989.

53 See Democracy: A Project of Group Material, op.cit.

54 See Lebovici, Ce que le sida m’a fait – Art et activisme à la fin du XXe siècle (Paris: JRP, 2017), chapter 14.

55 The Village Voice, 10 January 1989. On January 17th in the same newspaper, the critic Kim Levin reckoned that Group Material had now stepped into the traditional mould of the ‘curator’. Various texts were written in response to this.

56 In English, AIDS Panorama. An Exhibition on Life and Death. In 2013-14, Wagner organised, still at the nGbK, a second version of the exhibition, called LOVE AIDS RIOT SEX.

57 The following descriptions are largely inspired by the text ‘Group Material: MATRIX/Berkeley’, signed by Meyer and published for the occasion. See http://bamlive.s3.amazonaws.com/MATRIX_132_Group_Material.pdf, and

by Claire Grace’s study of the AIDS Timeline, a contribution to the series ‘The artist as curator’ conceived by Elena Filipovic for the magazine Mousse. Claire Grace, ‘Group Material, AIDS Timeline, 1989,’ Mousse Magazine 45 (2014).

58 Meyer, ‘Group Material’, ibidem.

59 Grace, ‘Group Material, 10.

60 Hubert Damisch, interviewed by Annette W.Balkema and Henk Lager, ‘Genealogy of the Grid,’ Series of Philosophie of Art and Art Theory 13 (1998) : 49-54.

61 The magazines were : Afterimage, Art&Auction, Art in America, Art New England, Artforum, Arts, Contemporanea, High Performance, October, Parkett, and Shift. (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 1990), 2.