The Burden of Names

Pierre Von-Ow

To cite this contribution:

Von-Ow, Pierre. ‘The Burden of Names.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/burden-names/.

Between 1951 and 1954, French historian Jacques Hillairet released his three-volume Évocation du Vieux Paris, a book in which he delves into the names of each and every Parisian street in order to, as the title implies, evoke its origins, to bring to life the evolution of its route, and, more generally, the history of urban planning in Paris since the Middle Ages. These books met with a great editorial success, and were commissioned by Jérome Lindon, the recently-appointed director of Les Éditions de Minuit, a publishing house whose founders were involved in the French Resistance. The actual and potential destructions of the Second World War had raised a great concern and these books somehow enabled readers, by way of an archaeology of the map, to regain possession of a space lost during the Occupation. Dictionaries of street names have flourished ever since, including even the names of metro stations.

In this respect, a recent controversy in France testifies to the symbolic weight associated with the naming of places. The story takes place in Corbeil-Essonnes, a working-class suburb of Paris, whose mayor decided to rename the main street, rue Léon Blum, after the former mayor, the billionaire industrialist and politician Serge Dassault, whose firm also happens to manufacture fighter jets. Citizens loudly protested against this decision, collecting signatures for a petition, noting the fact that Dassault had been sentenced for money laundering and cronyism. A hospital and a high school are located along the street in question, and the residents deemed it unacceptable that places of birth and youth come to be associated with Dassault and disconnected from Blum, who symbolized the hope for freedom that let him to found the French socialist party.1 What this unresolved baptismal conflict reveals is that the question is not solely who we revere in our maps, but rather how we consider and depend on the symbols attached to our own daily movements. Moreover, what is at stake here is the way we read maps in general, not only from a bird’s-eye view but also from the inside, digging into the depth of words, lines and unmodulated areas of pastel colours.

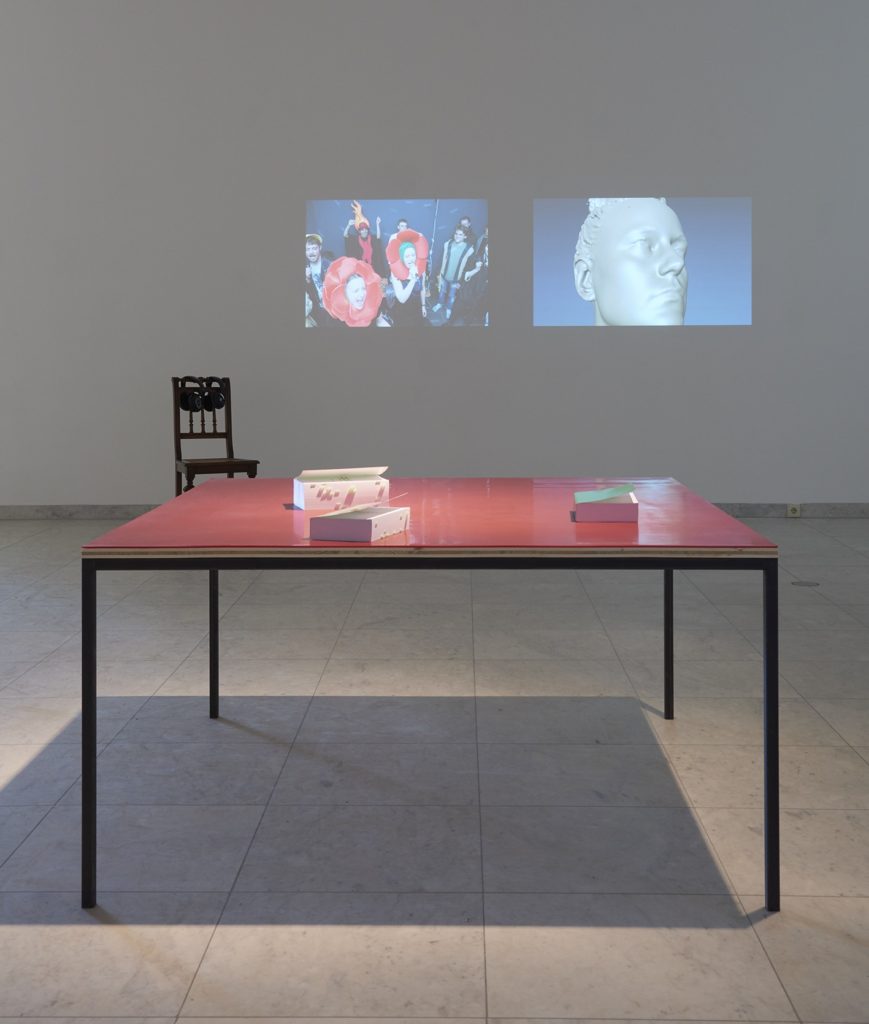

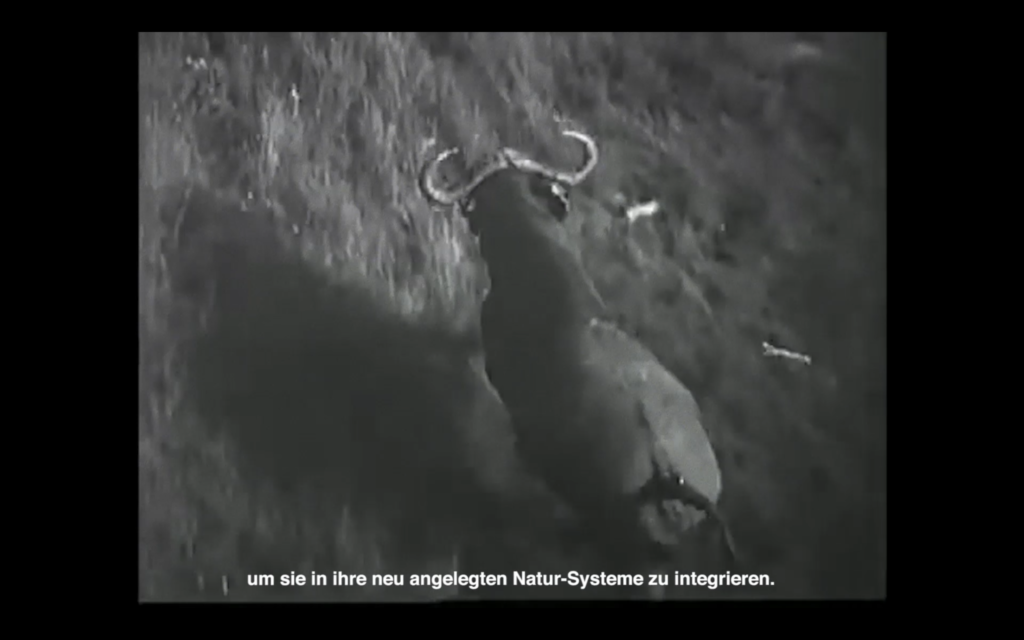

In a recent installation titled Paradise in a square (2016), artist Fari Shams examines systems of representation, and the cartography of knowledge. Her work consists of four interdependent elements, detached from a chronology, presented in a square room (Figs. 1 and 2). The first element is a short film composed of predominantly found footage from various visual sources and archives, juxtaposing Persian gardens with exploration, gaming and virtual reality, over the top of which the artist’s voice reads a narrative that is at times historical, at times theoretical, at times poetical. Other parts of the installation include: a double projection where the countless images and footage taken by the artist Nora Hansen of herself in a pursuit of fame, ultimately lead to her commodification as an animation figure using 3D modelling; a three-volume book generated in Wikipedia, consolidates Shams’ research notes; a recurrent neural network (RNN), that allows anyone to get more of virtually anything – in this case, more of the narratives found in the journal of explorer David Livingstone. This installation is a reaction to Shams’ trip to the Cologne Zoo, but the history of exploration and collecting leads her to make a connection between the categorisation of objects and the representation of the self in digital environments, suggesting that both are elements of a taxonomic system that is incomplete. As a way of tackling the aesthetic of montage, atlas-like systems of representation as well as the very act of reading, this article will draw on this specific work while extending its corpus of references.

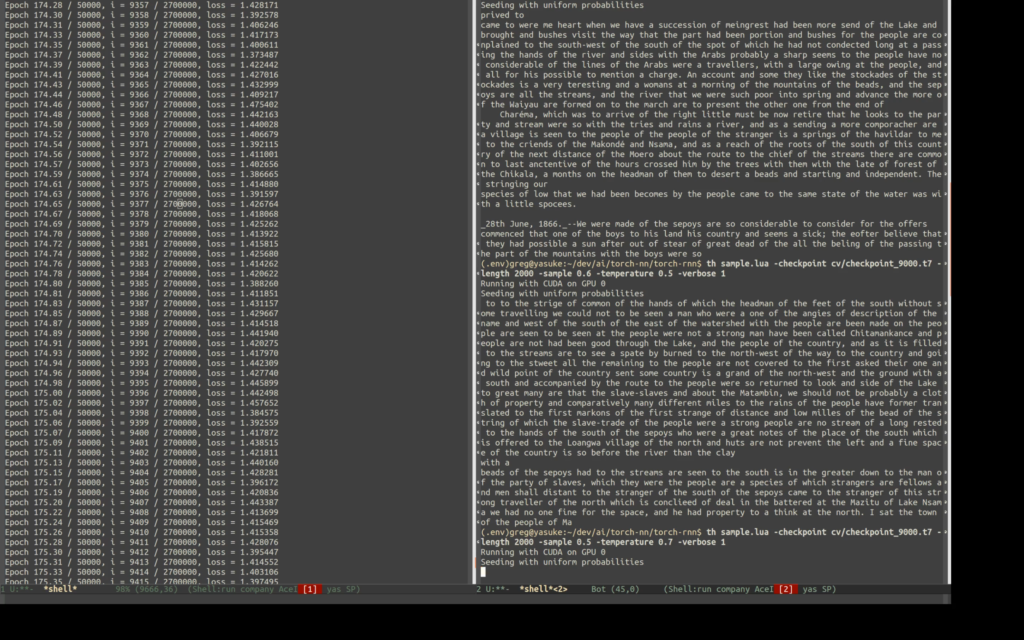

On a LCD screen, standing on the far right wall after entering the space of the installation, shown for the first time at Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, 2016, a recurrent neural network can be seen in the process of learning. Two books are presented on the wall. The viewer can pick up and read the first volume of the journal of David Livingstone (1813–73), the famous Scottish explorer, doctor, and missionary, ‘discoverer’ of Zambezi, alongside the newly generated journal presented in an identical (book) form (Fig. 3a). Ironically enough, Livingstone is today mostly remembered thanks to the words of his own discoverer, Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904). A journalist at the time, Stanley accepted the mission entrusted to him by the director of the New York Herald to find Dr Livingstone, who was thought to be lost somewhere in Central Africa, and of whom no one had heard for some years. The subsequent book Stanley published in 1871, How I Found Livingstone, resulted in overshadowing the travel of David Livingstone himself.

The genre of travel accounts can be described as tales of adventure, driven by multiple ambitions that include the discovery, navigation, mapping, and documentation of the world, and scientific projects that often served as a backdrop for colonial interests. Despite these scientific, economic, geographical, and religious aims, in these texts the literary approach predominated over the strict documentation of data. These tales satisfied a widespread and desperate need for adventures one preferred to live out vicariously. By using an artificial intelligence algorithm, Shams generates this product in her installation, thereby problematising its foundation. The neural network in question, developed by a PhD student in computer science and available online, copies the style of any given ‘text’ and, thanks to an algorithm based on probability distributions, it generates more text: when you feed it with a Bach score, it produces a – surprisingly good – new Bach sonata. And, in our case, the outcome is a fictitious volume of the journal in the style of Livingstone. This automated process of narrative building questions the validity of the tales that have inspired our imaginations over time. Nevertheless, the viewer notices on a single page of the new journal that the text doesn’t make any sense, due to the fact that this neural network doesn’t know any grammar (Fig. 3b). This resulting text reveals the statistically dominant interests and rhetorical tools adopted by Livingstone because the algorithm identifies and repeats them in the generated text. In this extract, one reads the word ‘sepoy’ several times, as well as ‘slaves’ hyphenated with ‘trade’ or another ‘slave’ – ‘slave-slave’. Most of the sentences are comprised of words relating to descriptions of people and lands, exposing Livingstone’s main concerns. Yet compared to the original journal, punctuation is sparse, and capital letters appear at random. In a way, this syntax conveys a sense of excitement, an impossibility to restrain, an enthusiasm in nonsensical descriptions and anecdotes that can only come about in the course of an impossible reading. Meaning is to be found in redundancies, and grasped with floating attention. Although the algorithm is unable to provide an endless sort of ‘exotic’ discovery for the reader, it nevertheless makes apparent the genuineness of experience that is inevitably filtered by language. Fari Shams’ installation highlights the weaknesses and subjectivity of descriptions that are taken for granted, the bias of textual and visual transmission, and the caution with which any sort of re-presentation should be treated.

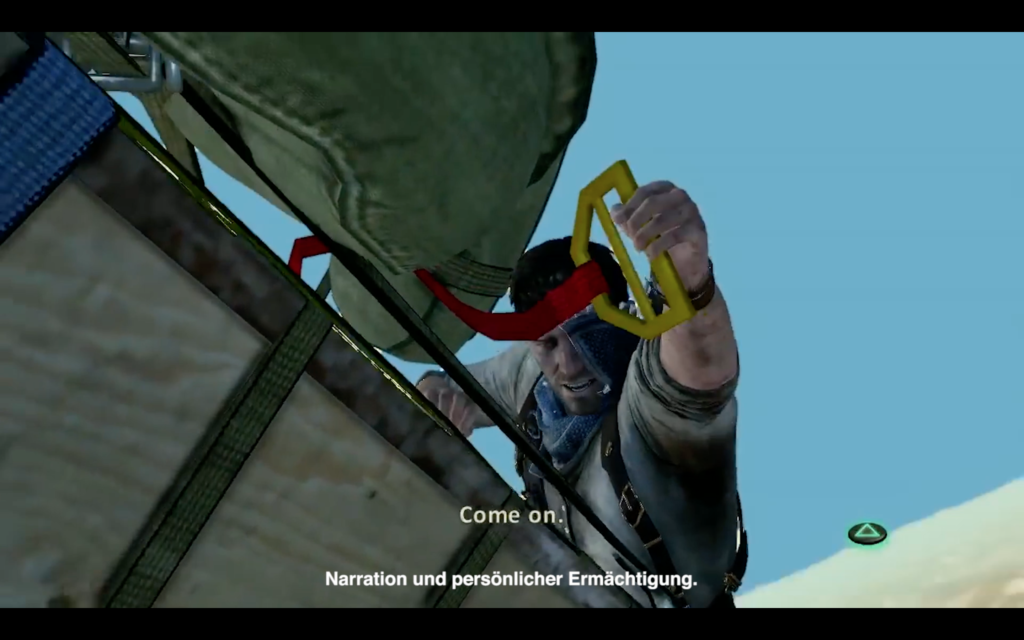

In the main film, Paradise in a square, projected on the main wall, about five minutes from the start, an excerpt of a video game shows a stereotypical action hero in military outfit jumping out of a moving plane, and trying desperately to catch a wooden crate, now in free fall, containing a parachute that would save his life (Fig. 4). Simultaneously, we hear the following:

The emphasis on surprise, struggle and determination in travel accounts, and the heroic tale that deliberately left out many real incidents and adventures because they might shake the probability of the narrative in the public estimation lead to a curious combination of empirical evidence, deductive theory, scholarship, emotional attachment, storytelling, and personal authority.

An account similar to Livingstone’s can be found in another journal, that of Dr Jean-Baptiste Charcot (1867–1936). The French explorer is best remembered for his expeditions in the Antarctic at the dawn of the twentieth century. On the 15th of August 1903, Charcot left Le Havre accompanied by 21 men on a boat he called Le Français, to embark on a trip of more than a year in the unpredictable seas of the South Pole. The book he published in 1906 is a genuine tale of adventure, recounting the discoveries and ordeals experienced by the crew day after day. Charcot had two role models: Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe. His diary mirrors these conflicting influences that characterise more generally any kind of travel account: the scientific narrative and the metaphysical novel.2 It is clear that Charcot wrote and reworked his text so that readers would identify with him in his quest, staging the épopée as a continuous struggle against elements for the sake of science and France. He presents himself as a leader, omitting his own weaknesses, and disclosing only scraps of detailed encounters with his sailors. Of course, writing necessarily requires a selection as well as an omission of existing facts. The process of identity building in Charcot’s journal mirrors Shams’ Paradise in a square, through the presentation of the life and work of Nora Hansen. This is done through a double projection on one side, showing the numerous selfies and videos taken by Hansen, while simultaneously on the other side a slow 3D modelling of her in the programme Maya takes shape simultaneously, using all this data to transform her into an avatar, an approximation based on her own documentation. This process of documentation and reproduction of everyday life, similar in spirit to the writing of Charcot’s diary, is intentionally disclosed, its privacy made transparent, in anticipating a continuation through the imagination of its audience. It is therefore produced in the context of this Erwartungshorizont. A piecemeal description leaves room for interpretative reading. As Wolfgang Iser has argued, vagueness is the essence of literature, quoting in this regard what William Thackeray once pointed out, that is, the unwritten part of books is always the most interesting.3 As we will see with atlases, the space between images or words, which ‘may be looked upon’, according to Henry Fielding, ‘as an Inn or a Resting-Place’,4 is a bet made by the author on the capacity of his audience to fill in the blanks and complete the narrative.

1. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

2. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

3a. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

3b. LCD screen showing the recurrent neural network and the journal of David Livingstone together with the one generated by the algorithm, courtesy of the artist.

4. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception (2011), courtesy of the artist.

5. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

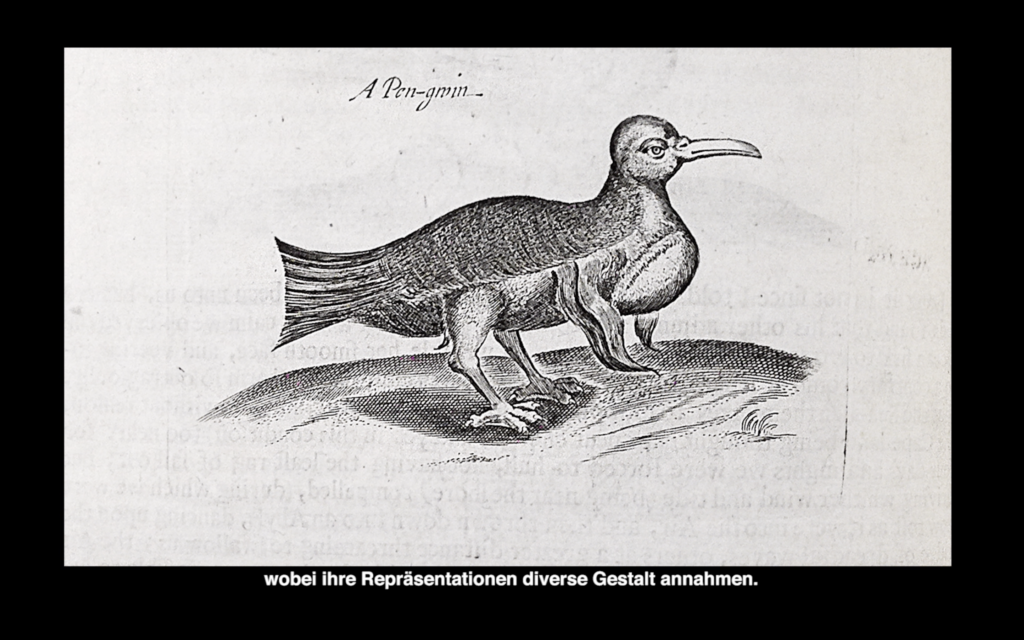

Charcot sailed in the wake of Jules Dumont d’Urville, who led an Antarctic expedition in 1837–40. While sailing, he often read some pages of his illustrious predecessor’s accounts, whose descriptions he compared to the passing reality he was witnessing. Somehow, descriptions can become a form of appropriation to such an extent that the interaction with something new always references a pre-existing account. Shams is also dealing with this question in the film Paradise in a square. One of the images she includes is a print taken from Thomas Herbert’s 1677 Some Years Travels into Diverse Parts of Africa and Asia the Great. It shows a ‘Pen-gwin’ found in ‘the Pole Antartique’ (Fig. 6). Herbert’s original description was as follows:

we saw abundance of Pen-gwins, in Welch White-heads, agreeable to their colour; a Bird that of all other goes most erect in its motion, the wings or fins hanging down like sleeves, covered with down instead of Feathers, their legs serving them better than their wings; they feeed [sic] on fish at Sea and grass ashore, and have holes to live in like Conies; a degenerate Duck, for using both sea and shore, it feeds in the one, breeds in the other; is very fat and oily, and some adventure to eat them.5

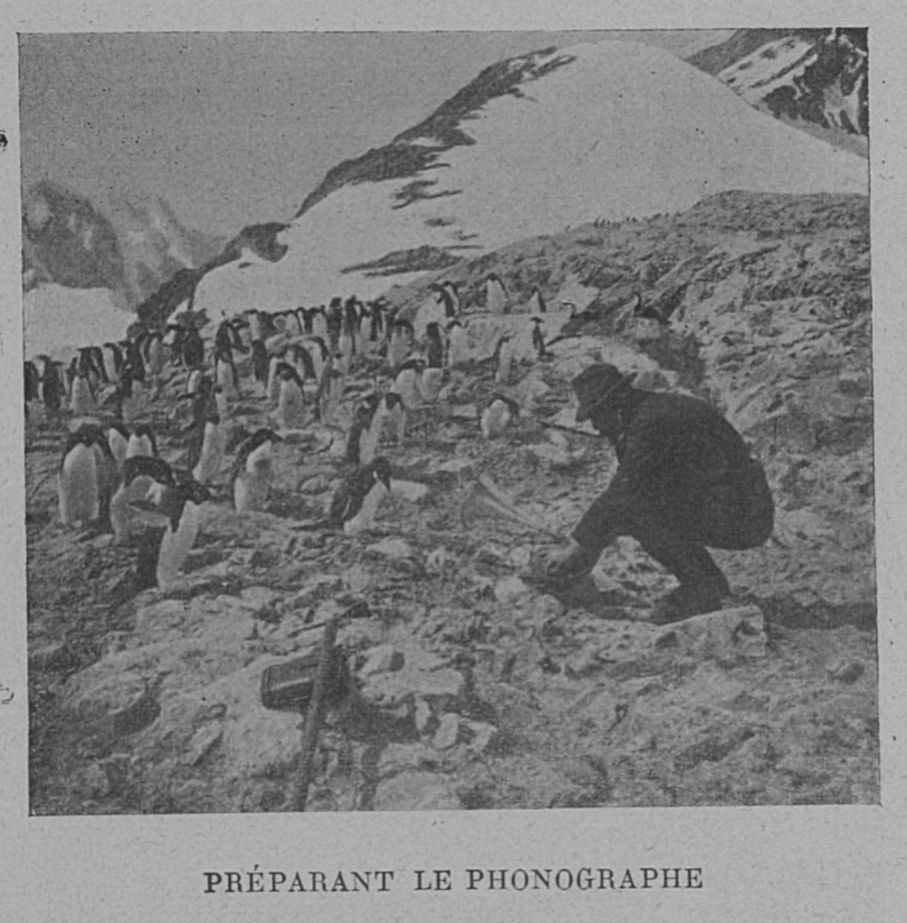

The exotic animal is systematically compared to a common, ordinary species, whether a cony, a duck or even a man – the thought that wings look like sleeves for example – all of which culminates in the very act of its consumption. Dr Charcot devoted several pages of his journal to penguins as well, and ended up playing them music on his phonograph (Fig. 7). He starts his description by comparing their community to a village and praising their ‘communist’ aspect; then he compares their mode of communication to the ‘couin-couin’ of ducks and notices that these ‘phonetic signs [are] almost equivalent to speech’. But the most striking part of this description is when he states that they look like ‘little girls with their white apron, Dominican fathers, short women in black coats’.6 If description is appropriation, its most efficient tool is then metaphor, the use of ‘as if’, which helps minimize, if not utterly negate, exoticism. In this regard, German philosopher Hans Blumenberg has observed: ‘The metaphor is projection, anthropomorphic domestication of nature serving the subject reflecting himself through it’.7

These accounts of discoveries ultimately aimed to validate a wider conquest of territories. As Morton Stanley did with the blank zones on the map of Africa, Charcot intended to document the immaculate ice floes of the South Pole. Yet quite apart from the national pride of putting a French name on a map, Jean-Baptiste Charcot also had to make a name for himself. He was indeed the son of the famous Dr Jean-Martin Charcot, who taught the basics of psychiatry to young Sigmund Freud at Hôpital de la Salpêtrière in Paris. The explorer explicitly mentions the burden of his own surname: ‘I felt on my shoulders such a heavy responsibility to bear this name that I swore to myself I would bear it with dignity’.8

In a sense, it is striking to realize that father and son had two opposite but not entirely conflicting ambitions. Both invented new fields, in the sense that they were the first to describe and name them. Pierre Escudé states that ‘mapping the unknown means discovering the alienated part of the world’,9 alienation being used in both senses of otherness, namely the unknown lands of the world and of the self. In Invention of Hysteria, Georges Didi-Huberman studied the perverse method of Dr Jean-Martin Charcot so as to mark out this illusory mental illness. ‘He named [it] hysteria. He distinguished it, notably from epilepsy and from all other mental disorders. In short, he isolated hysteria as a pure nosological subject’.10 In the preceding pages, Didi-Huberman quoted Nietzsche in a reflection that can be applied to any form of exploration: ‘Even in the midst of the strangest experiences we still do the same: we make up the major part of the experience and can scarcely be forced not to contemplate some event as its “inventors”’.11 Dr Charcot’s father spent his lifetime locking up women with contradictory symptoms, so as to domesticate madness. Dr Charcot’s son sought out to encounter the vast Antarctic continent in order to domesticate wilderness. Yet, whereas the former was mapping pains on the body of his patients with the aid of photographs and drawings – a clinical aesthetic – the latter marked out and labelled the lands and biotope of the South Pole.

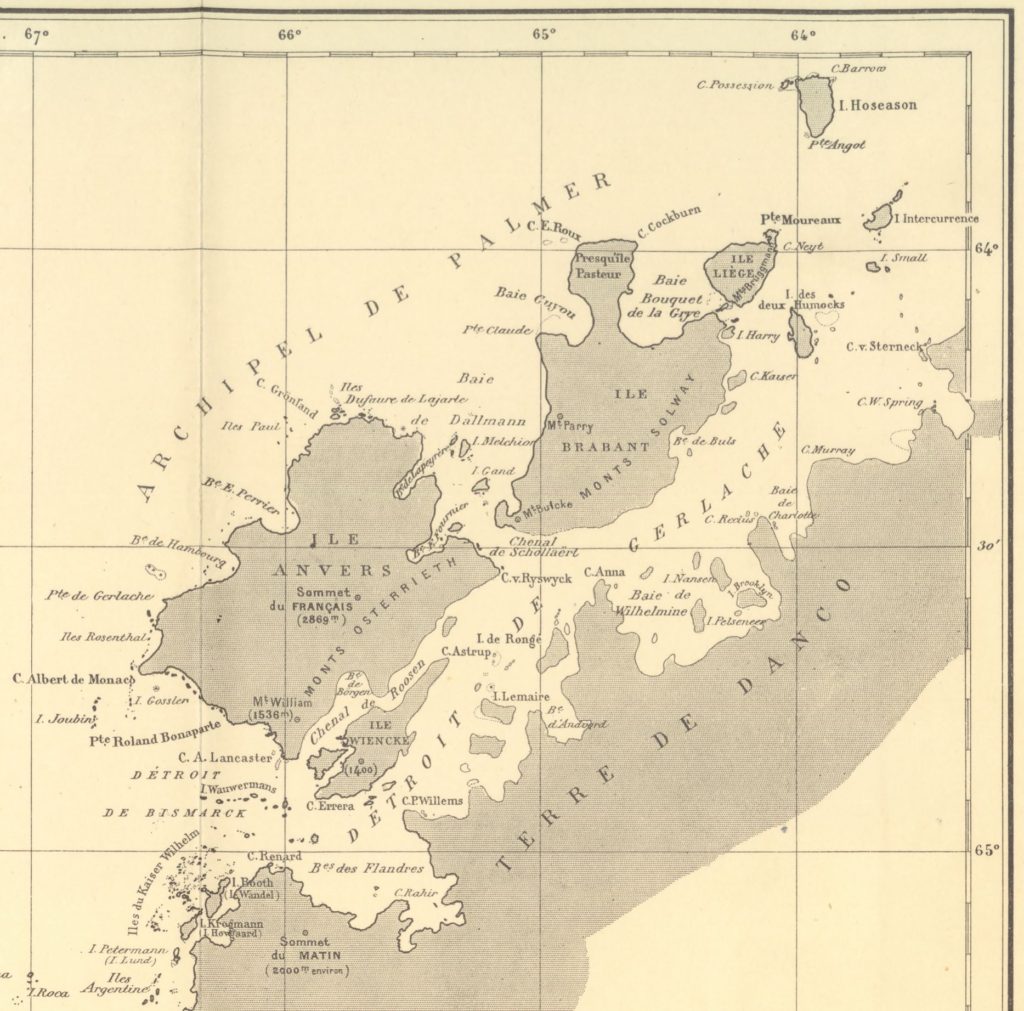

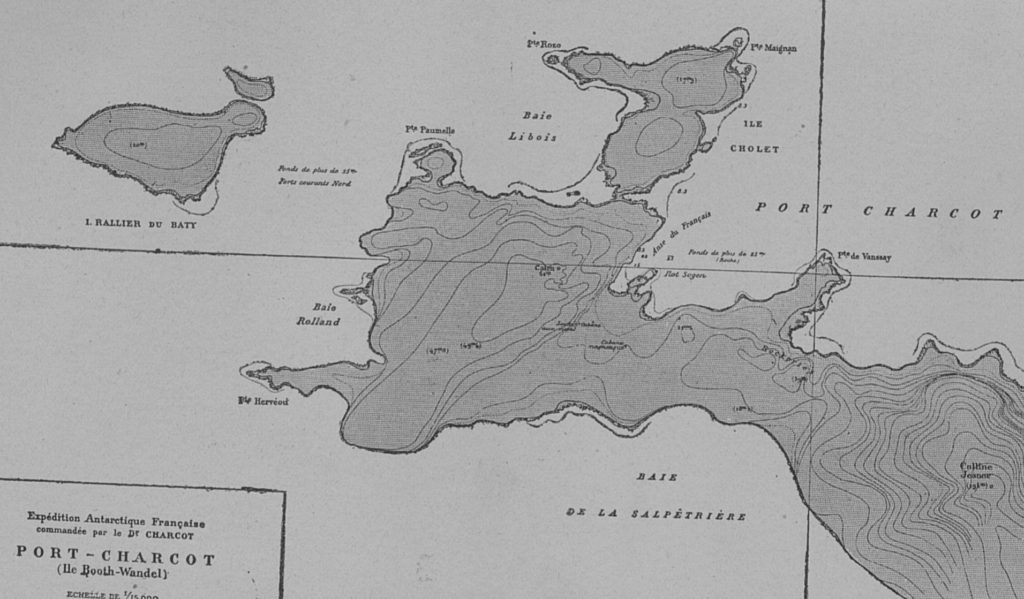

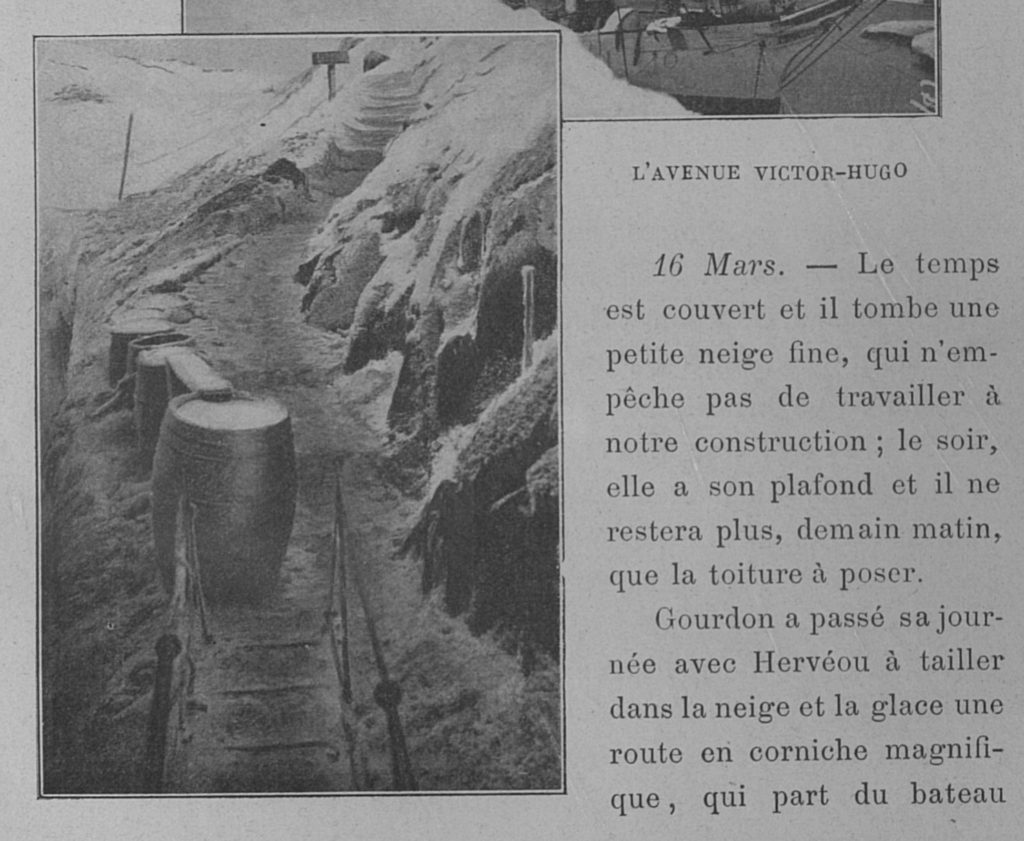

Jean-Baptiste Charcot’s vision was focused on taking possession of some lands in order to compete with the overseas exploration undertaken by Sweden and England. At this time, the Terra Incognita Australis was one of the last regions of the globe left undiscovered and as such one of the most sought-after. In laying claim to one’s property the only thing left after putting up a flag was to name it. Captain Foster of the British navy decided quite promptly to baptize the headland of Hoseason Island ‘Cape Possession’ in 1829, mistakenly believing that it was part of a vast piece of land (Fig. 8). As for Charcot, he personally decided to name the harbour in which his crew spent winter ‘Port Charcot’, and located it not too far from the ‘baie de la Salpêtrière’, that he baptized in a tribute to the asylum ran by his father (Fig. 9).12 He then named a small mountain after his wife, Jeanne. An islet was named Sögen, after the crew’s dog who just passed away, and buried in its ice. The Duke of the Abruzzi, an illustrious explorer, lent his name to another large mound. And the pathway they dug in the snow between their ship and their storage was named ‘Avenue Victor Hugo’ (Fig. 10), after the grand-father of his wife and national hero. But their most remarkable seizure was probably the ‘Sommet du Français’ right in the midst of Anvers Islands (Fig. 8).

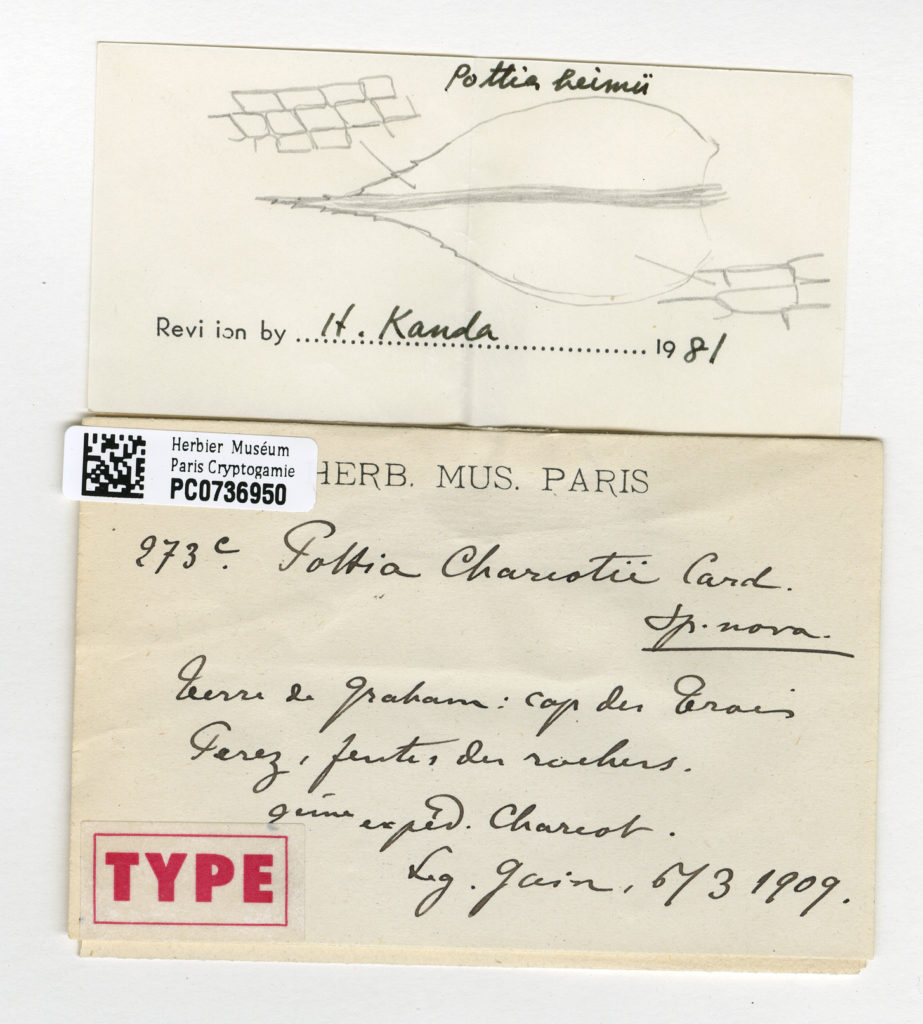

However this process of naming extended beyond geography. Numerous plants, particularly seaweeds species, brought by the expedition and bequeathed to the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris bear names ending in ‘chacotii’ (Fig. 11). Collecting and naming are alike, just as are drawing a map and creating a Wunderkammer, in the sense that both expose a desire to organize reality by reducing it to categories and strict outlines. Travel accounts can be viewed as expeditions into our systems of representation, a probing of language and a confrontation with previous attempts to name places, items or people. Orientation in space is also an orientation in time: the archaeology of maps and herbariums are better read as palimpsests than read in a horizontal fashion.

6. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Thomas Herbert, Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa and Asia the Great, 1677, courtesy of the artist.

7. Paul Pléneau, Preparing the Phonograph, circa 1904, in Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le ‘Français’ au Pôle Sud, 1906, source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

8. Detail from the general map of shores explored by the Expédition Antarctique Française led by Dr Charcot (1903-1905), in Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le ‘Français’ au Pôle Sud, 1906, source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

9. Detail from the map of ‘Port Charcot’, in Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le ‘Français’ au Pôle Sud, 1906, source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

10. The Avenue Victor-Hugo digged into snow, in Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le ‘Français’ au Pôle Sud, 1906, source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

11. ‘Pottia Charcotii’ Card (1909) in the herbarium of the Musée d’histoire naturelle, Paris, copyright reserved.

12. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, courtesy of the artist.

13. Richard Barnes, Giraffe, Academy of Sciences, 2005, part of the series Animal Logic. © Richard Barnes.

Regarding the process leading to the appropriation of environments, Shams film in Paradise is also composed of extracts of a documentary on the New York Museum of Natural History showing scientists at work on the fur of a bear within a diorama (Fig. 12). Armed with paint and varnish pistols, the scientists are busy perfecting the fine details of its appearance. The extreme methods they employ, and the toxicity of the products they use, all aim to create the perfect illusion of wild life. These images remind us of the series of photographs by Richard Barnes titled Animal Logic. These photos focus on the mechanisms of display used in museums of natural history around the world (Fig. 13). These images capture a sense of the violence that is applied to nature in the very act of its replication for the purpose of exhibition. A recent project by German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans also resonates here: the juxtaposition of images taken in two world trade fairs, the Fespa Digital, devoted to digital printing, and Fruit Logistica, the international trade fair in Berlin for fresh industry products. Images of printing machines and inkjet prints adjacent to booths staging fruits, produce a striking montage that evoke a sense of confusion and embarrassment about the commercial and cultural appropriation of nature. What is at stake in all these projects is the dramatization of nature, in other words the very notion of artificiality, and moreover how in time, we come to regard that artificiality as the ‘real’ instance in comparison to its less impressive physical counterpart.

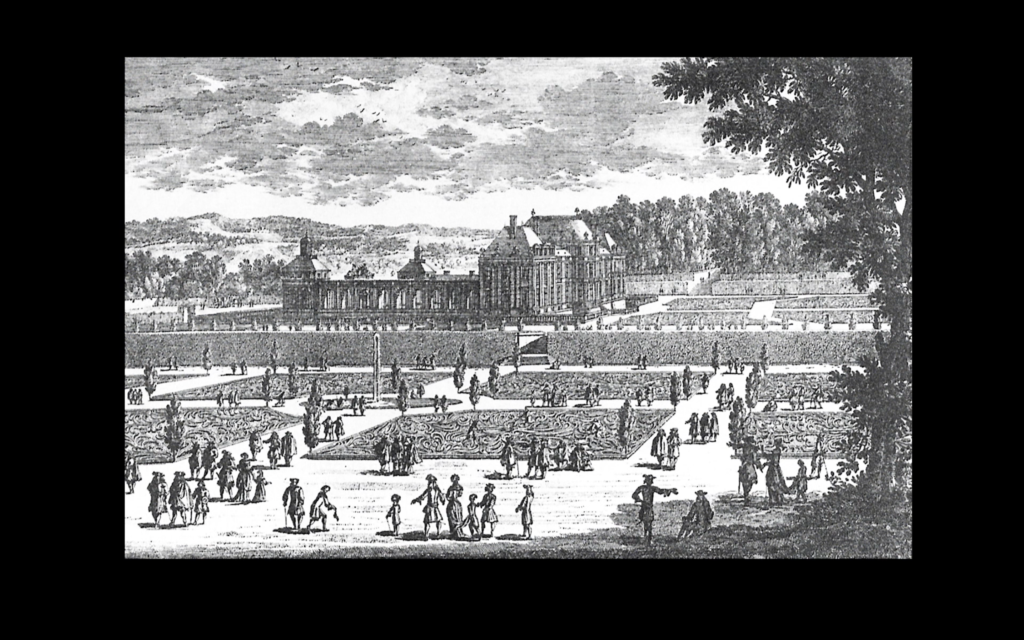

To think of gardening in these terms, one could argue that it is, in fact, the management of nature. If one takes on a historical perspective, Versailles was definitely the symbol of artificiality and replication, a theatre conceived as a succession of visual effects – labyrinths, Galerie des glaces, a plethora of hidden doors and corridors. The subject of countless studies, the gardens of Louis XIV embody the application of possession and the mastering of nature, which is most obvious from a bird’s-eye perspective. The aptly named Sun King wrote the ideal path of a walk through his gardens, whose starting point was on the patio at the top of the stairs leading to the parterre de Latone. The courtiers could thus embrace the whole garden in which they would then follow the path of their nonchalant guide. As such, jardins à la française have been regarded mostly as a celebration of sight and order. The remaining documents from that time that show bird’s-eye views of French gardens convey this careful sense of restraint framing the random course of conversations, such as this image of Château du Raincy, included in Shams’ video, whose gardens were designed by Le Nôtre in the 17th century (Fig. 14).

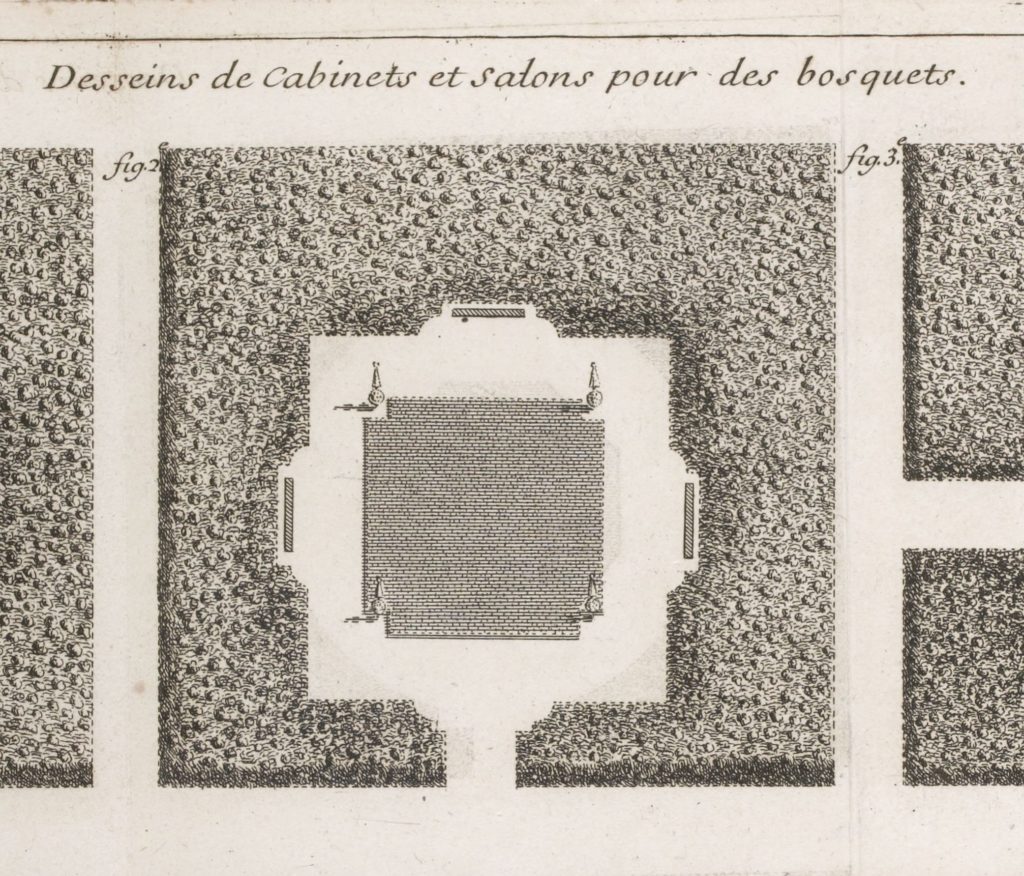

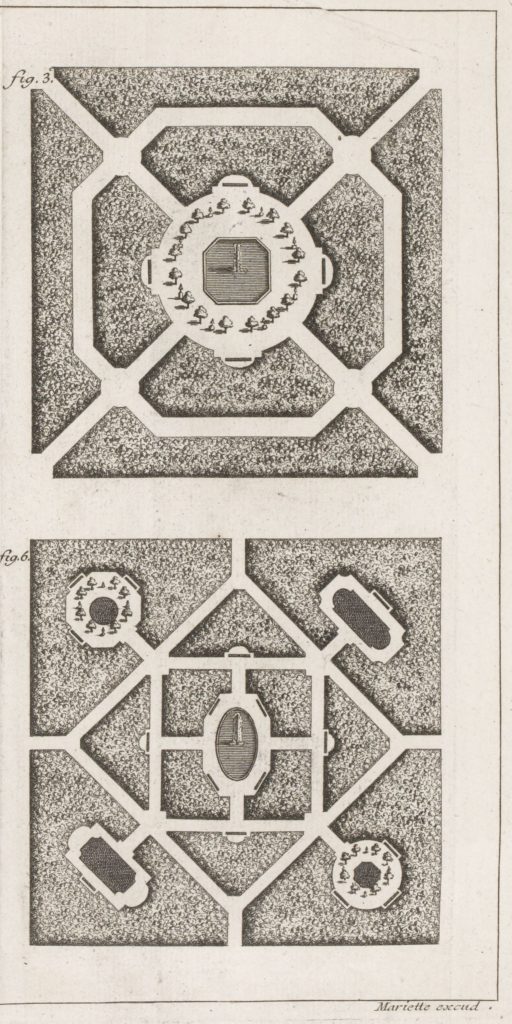

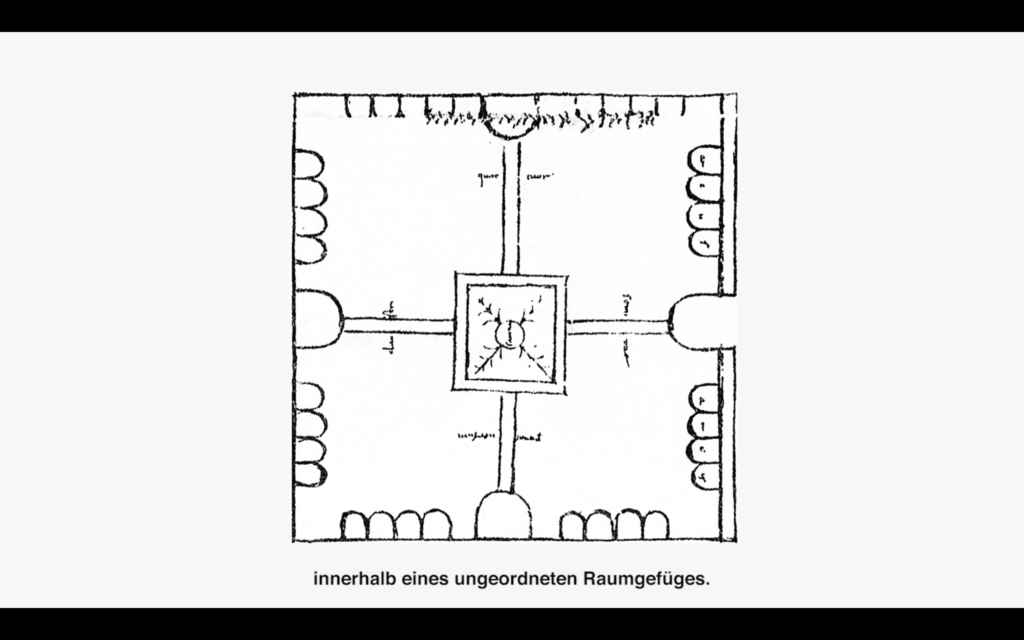

The square referred to by Fari Shams was a recurrent shape in their maps, satisfying the aspiration for algebraic harmony. In his 1709 Theory and Practice of Gardening, Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville described a method to design jardins de propreté (gardens of uprightness), outlining every detail, from the choice of position to the species of plants to grow with various defined shapes. The book itself is arranged in a thoughtful and rigorous manner, demonstrated by a notice addressed to the bookbinders for the proper placing of ornamental prints. He provides the gardener’s apprentice with models of square-shape cabinets and copses whose drawing is strictly symmetrical (Figs. 15 and 16). These prints bear a close resemblance to the schema of the Chahar Bagh, the Persian garden that is the starting sequence of Shams’ film (Fig. 17), and assign a shape to the concept of heterotopia. Michel Foucault, in his well-known conference Of Other Spaces,13 took the example of traditional Persian gardens to state that heterotopias – meaning the utopia realized in physical space, whether it is a brothel or a colony – juxtapose discrete sites in a single sacred space. In this case, the garden – pari-daiza in Farsi – gathers together in its four corners the four parts of the world, forming a shape that can also be found in Oriental rugs regarded as reproductions of those artificial microcosms:

The garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space. The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world. The garden has been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia since the beginnings of antiquity (our modern zoological gardens spring from that source).14

14. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Perelle, View of the Château du Raincy, 1685, engraving, 28,5 x 37 cm, courtesy of the artist.

15. Detail from the plate 5 Desseins de cabinets et salons pour les bosquets, in Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, La Théorie et la pratique du jardinage, où l’on traite à fond des beaux jardins, appelés communément jardins de propreté, Paris, J. Mariette, 1709, n. p., source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

16. Detail from the plate 3 Desseins de Bois de haute futaie, in Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, La Théorie et la pratique du jardinage, où l’on traite à fond des beaux jardins, appelés communément jardins de propreté, Paris, J. Mariette, 1709, n. p., source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

17. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Chahar Bagh, courtesy of the artist.

In pointing out the relationship of zoological gardens with planted havens, Foucault is suggesting a common ambition applied to flora and fauna, which is this consistent desire to restrain wilderness within strict borders. According to Saint-Simon, the tireless chronicler of court, Louis XIV ‘enjoyed to tyrannise nature’.15 Domestication of nature was indeed realised in at least three different ways. The first way was the control of emotions and behaviours, the so-called ‘civilizing process’. Individuals had to refine their body and speech expression by struggling against their natural tendencies. The second one was the strictly geometrical drawing of Le Nôtre’s gardens, confusing parterres and tapestries. Marquis de Girardin, the designer of Ermenonville, the famous parc à fabriques inspired by English-style gardens, acrimoniously considered that Le Nôtre ‘completed the massacre of Nature in subjecting everything to the Architect’s compass…plantations immediately followed the guiding line of symmetry’.16 In his words, one may read the latter term as cemetery, the point where nature is pushed back and prevented from expanding above and beyond a predetermined fixed shape. This is particularly striking if one reads the method for sticking lawns outlined by Dezallier d’Argenville. Although the outcome was to be velvet-like, the description was eloquent in terms of the brutality applied to nature. The idea was to transplant square parcels of pastureland into lavish gardens and literally crucify them with dowels onto prepared soils. But the main problem was maintenance because the gardener was to prevent turf from growing, from overflowing the sharp outline of its design:

one reaps the lawn every fortnight. The more grass is clipped, the more it thickens and embellish…One must also trim from time to time and mark out the edge of lawn pieces according to the guiding line; this is what makes uprightness [propreté], because otherwise grass would move away and go around into the path, what would interrupt shape and design of compartments.17

This method reminds us that Louis XIV was also – with the help of Vauban – the inventor of fortified borders with Low Countries that one used to call the pré carré (the square meadow),18 in other words another perception of a paradise in a square. This is a reminder of Bertolt Brecht’s words: ‘Der Sturm, der die Birken biegt / Gilt für gewalttätig / Aber wie ist es mit dem Sturm / Der die Rücken der Straßenarbeiter biegt?’19 One considers as violent the river that takes everything away in its trail, while never pointing out the violence inherent in the edges surrounding it. The restrictive structures, namely our symbolic as well as physical fences, have to be questioned first. Finally the third conspicuous example of domestication is the zoo. As perfectly summed up by Nikola Jankovic, Louis XIV is a transitional figure in the lengthy history of animal parking. He is responsible for transforming seraglios from the Renaissance into ménageries; in a word he exchanged the open park where exotic animals could frolic in an unfamiliar environment and amuse owners with entertaining fights, with narrow fenced parcels of land in which species were separated from each other for a purely visual delight.20 This movement of enclosure was followed by the parallel development of natural sciences and the beginnings of taxonomy. In her commentary, Fari Shams dwells particularly on this shifting of paradigm (Fig. 18):

naturalists actively directed the perspectives that the artist took when carrying out studies of nature. They focused on the essential characteristics of what they were depicting in order to highlight specific traits that justified their choices of classification. Selecting, comparing, judging and analysing what was to be communicated was the task of the experienced observer guiding this process. Accidents, deviations and impurities needed to make way for the common and the general…

The omission of errors, uncertainty, variation and exception in favour of idealized examples of nature results in our shared understanding of it. Yet this is just one of a number of equally exchangeable ways to organize the world. The spaces we occupy embody a sense of organization. Each in its own particular way is shaped by the will to give it meaning.

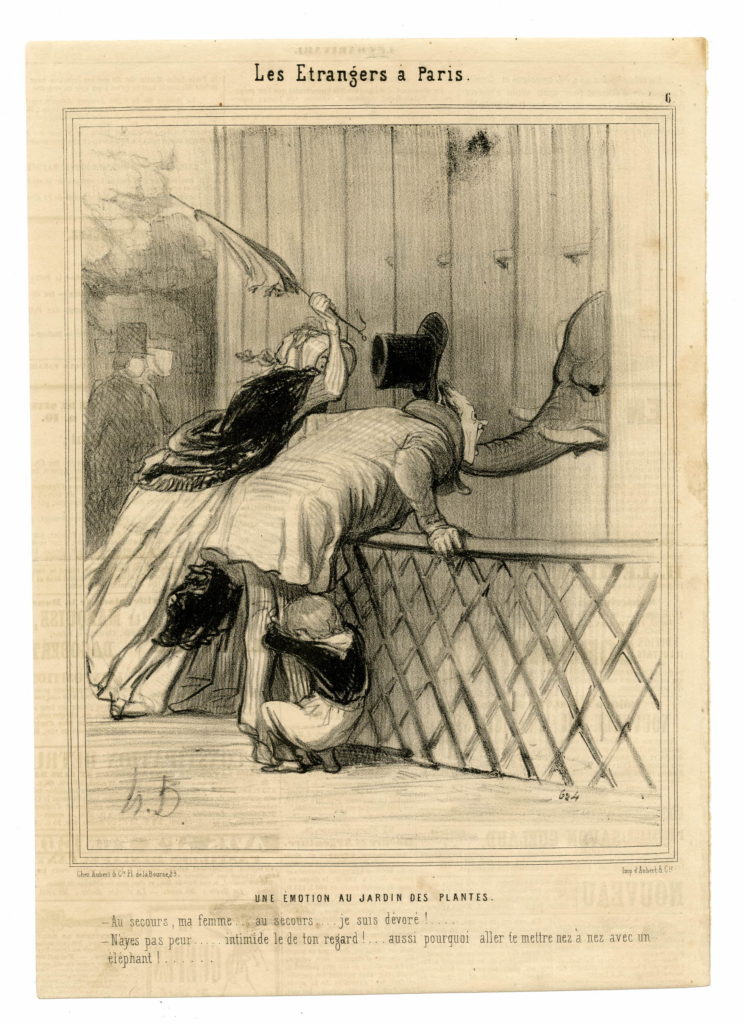

As discussed above in the case of Charcot, description is appropriation by the means of language; it is reducing diversity to a few traits, thereby enabling us to create virtual categories. The gaze of natural scientists oriented towards this aim couldn’t be but selective; the information left out permits the production of images and not merely copies. A caricature of French artist Honoré Daumier brilliantly parodies this alleged power of the gaze. At his time, the 19th century, menageries had been transformed to botanic gardens, more concerned with the well being of animals. This period coincided with the French Revolution and a broader liberating move, which can also be noticed in psychiatry. Buffon (1707–88) first used the term ‘acclimatization’, a less brutal and radical method than the mere alienating isolation.21 Since then, due particularly to the burgeoning of World Fairs, zoological gardens became zoos, namely popular amusement intended for Sunday strollers – referred to by Walter Benjamin as the flâneur. In Daumier’s cartoon (Fig. 19), entitled Emotion at Botanical Garden and part of the series Strangers in Paris, we might wonder who, of the elephant and dressed up provincials, is the actual stranger. The dialog in the caption is as follows:

— Please darling, help me… help… I’m being devoured!…

— Don’t be scared… intimate him with your gaze!… what an idea of coming face to face with an elephant!…

It distance, therefore, facilitated by the gaze and language, that facilitates the establishment of categories and the drawing of maps, the gaze of Louis XIV, of natural sciences, of strollers. It is distance that straightens distinctive features in order to contain them within bold outlines, distance which sometimes has to be confronted with reality. It ‘is indeed from behind their own grids that human beings can look at caged animals.’22 The established representation of the world is presented through the scientific method, which defines the framework of our apparent perception as ‘the antidote of the vast variation present in the unmediated encounter with nature’.23 (Fig. 20).

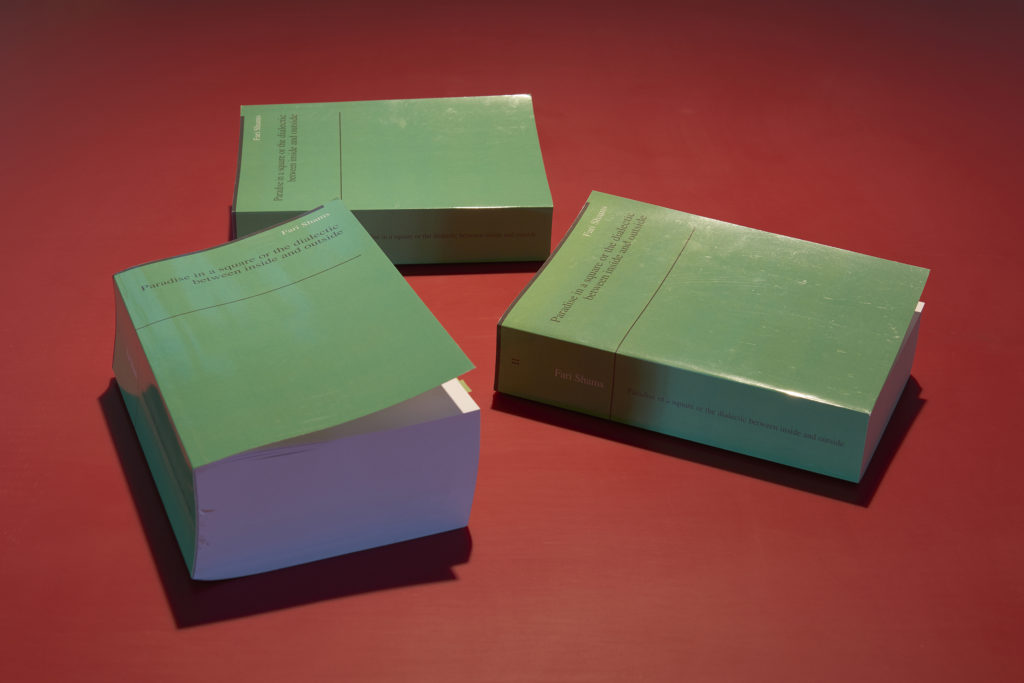

Paradise in a square is about zoos. Yet, as with the methods adopted in the Haiku, is it never explicitly mentioned. The three volume book placed on a square table in the middle of the installation (Figs. 21a and b) directly addresses the problem of too much data. In generating this encyclopedia of the history of zoological gardens using a service offered by Wikipedia, Shams decided not to consider the inclusion or omission of topics but instead collected all of her research notes. Her solution to the superfluousness offered by this mechanism was to create bookmarks relating topics across the three volumes, thereby insisting that there is always a deliberate path through this maze. And ultimately Shams’ installation as a whole, as well as in its parts, formally feels like a rejection of abbreviation.

The idea of assigning a restrictive category to someone or something has a telling name: pigeonholing. In a sense, some words reveal more than what they exclusively signify, through etymology and also with regard to their context, whether it is in a phrase, on a map, or in a dictionary. This peculiar example of Charcot is striking, because an icefield is liable to infinite movement in its shape, to melt at the whim of global warming that it is regulating to a great extent. What do these lands discovered by Charcot look like today? What do these names really represent? A similar evolution affects language. Georges Bataille used to say that definitions are ‘mathematical redingotes’ of things, locking them up into a shape supposedly still. Far from considering this kind of volatility with anxiety, Georges Didi-Huberman has widely celebrated ‘worried knowledge’. In the numerous texts he devoted to Aby Warburg, Sergueï Eisenstein, André Malraux, or Jean-Luc Godard, he has tirelessly demonstrated the virtues of atlases and montages in the endlessness of their meaning. As such, an atlas is seen as ‘a tool, not for the logical exhaustion of given possibilities, but for the infinite openness to the possibilities that are not yet given’.24 Atlases are perceived in opposition to the neat order present in albums and catalogs. However, he suggests the possibility of reading dictionaries according to this ‘atlas principle’, considering double pages dialectically. Taking an example in relation to our subject of study, one could notice for instance that in Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) ‘paradigm’ and ‘paradise’ share the same page 1447. If taken for granted, alphabetical order somehow elicits the idea that concreteness inevitably precedes utopia. This can, however be negated by an atlas reading, after noticing that ‘paradox’ is also on this very page. Furthermore, the way we now commonly read these dictionaries online, namely scans of single pages one can access through search engines, precludes the possibility of a random encounter of a word located on the opposite page, by serendipity. This purely vertical reading, somehow similar to GPS localization, suggests that words are merely pigeonholed into encyclopaedias and as such, appear as a prejudicial anti-atlas mode of presentation.

If one returns to the output generated by the neural network of Paradise in a square, one assumes that perhaps the best way to read this impossible text would be an index of common names, revealing their recurrence. As American artist and critical theorist Joseph Grigely, pointed out in his article about Shams’ European Civilization, Peter the Great and the Order of Things (2014), an index always ‘reflects on our desire for empirical knowledge by assembling bits and pieces of the world in a single place’.25 Looking over Livingstone’s virtual journal we notice assemblages, and tokens of words we do not necessarily pay attention to while focusing on the content. When a text doesn’t make any legible sense, form becomes a refuge – ‘the sign is like a window we go through to one’s liking’.26 In this regard, talking about the influence of Structuralism on the way we consider space in the second half of the twentieth century, Foucault notices:

We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein…Today the site has been substituted for extension which itself had replaced emplacement. The site is defined by relations of proximity between points or elements; formally, we can describe these relations as series, trees, or grids.27

However the interpretation of an atlas cannot be exclusively horizontal – relating images according to their location on a flat surface – in the same way that the prints of Dezallier’s treatise of gardening are incomplete due to their flatness. André Le Nôtre considered his gardens to be surprising – shall we say entertaining? – playing with scales and perspectives, imagination and memory, and this could only result in wandering though the space. The copses referred to above, when given a third dimension, are actually ‘rooms of greenery’, intimate gardens hidden within artificial forests – let’s say ‘chambered landscapes’.28 The stroller is given the choice to follow any path, get disoriented and end up randomly in cabinets of foliage. This physical experience of space is part of what we should call the vertical reading of gardens that may be applied to all patterns of knowledge, and particularly atlases.

In Reading Rectangles, Joseph Grigely tackled the slight nuances between legibility and readability of images. He used the example of Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, an unfinished group of panels on which images from various sources were pinned, disconnected from their original place and meant to disclose the enduring nature of motifs among the whole history of representation, in particular the Dionysian violence of antiquity. Warburg wanted to produce a history of art exempt from names. The idea was to reveal supra-individual, transversal flows, independent from chronology and space. As suggested by the scissors one discerns on the right edge of the photograph reproducing the Plate A of Mnemosyne, he removed captions so images might be considered by themselves. In a sense, Warburg’s reproductions and Dezallier’s squares of pastureland are similarly cut off from their initial environment to become integrated on a flat surface. Grigely paid particular attention to the background of these photographs and noticed that, nonetheless, most panels were laying against bookshelves:

The rectangles are not always perfect Euclidean constructions…The presence of the books, and the way many of the images overlap each other, remind us that images do not come to us in detached from history: this history is always latent, sometimes, as here, hiding in the shadows created by the photographer’s lights. The edges of the panels sometimes appear irregular because of the effect of the shadows on the panels: the panels appear less as individual units than they seem to be parts that have broken off from a larger whole.

Plate A is particularly interesting as it features the design of animals associated with constellations, a map of migrations between Europe and the Middle East, and the family tree of Florentine bankers. Didi-Huberman interprets this as Warburg’s agenda to ‘offer a transversal knowledge of this inexhaustible historical (family tree), geographical (map) and imaginary (animals of the Zodiac) complexity’.29 It is also three different ways of representing something confined to space and time, and to give shape to the unknown. Warburg considered it rightly as ‘Different systems of relations – cosmic, terrestrial, genealogic – in which mankind is engaged’ and wrote behind the panel: ‘1. Orientation 2. Exchange 3. Social classification’.30 He was obsessed with the question of distance, whether it was in time or in space. But although his Bilderatlas Mnemosyne was a denial of those distances and hierarchies among visual materials, Warburg was worried about the abolition of distance brought by modern means of communication. In the conclusion of his lecture on the snake ritual in Pueblo culture, he wrote:

Telegraph and telephone are destroying the cosmos. But myths and symbols, in attempting to establish spiritual bonds between man and the outside world, create space for devotion and scope for reason which are destroyed by the instantaneous electrical contact.31

Warburg regarded immediacy in communication as a threat to the poetical interpretation of silence and the unknown. He astutely foresaw that while drawing people closer, technologies also keep them away from their environment. With reference to this, Shams’ Paradise in a square extends the narrative towards the end of her film to the dilemma of the individual who has inherited this history of pigeonholing through various modes of representation. The film begins and ends with the problematic of isolation: the Persian garden with its ‘four corners that prevent continuity’ parallels the ‘walled gardens’, ‘online environments where users go for information, communications, and commerce services and one that discourages them from leaving for the larger digital world’ (Fig. 22).

What happens when the immediacy of communication immerses the individual in a space that in terms of its structure is more perfect than physical reality with all its rigid parameters that cannot be redefined and reprogrammed? In her film, Shams includes excerpts of the ‘Starcraft Championships’, part of an e-sport that is taken very seriously in South Korea, and attracts many young players that spend the majority of their day ‘training’ to play on a competitive level. These players are all connected to each other online, but a bird’s eye view of the players in training has a remarkable resemblance to the zoo, and its modes of surveillance. Shams’ main concern with this scenario is the uncanny relationship that results between work and play. This is not restricted to gaming. The presentation of the life and work of Nora Hansen in the double projection shows an individual driven by an obsession with fame who constructs and defines her image through selfies and videos. These in turn seem to be the input to a real time 3D modelling of her as an avatar, in other words this abbreviated version of the self. As have seen with other examples presented throughout this essay, whereas our traditional systems of knowledge have failed us by cropping too much information out, in the context of using computing power and by conversely including infinite input for processing, we do not seem to have come closer to revising our modes of representation.

18. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, The New Adventures of Tarzan. Based on the Novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1935), courtesy of the artist.

20. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Hüpfurgen-Land, Düsseldorf, courtesy of the artist.

21a. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

21b. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, mixed media, 2016, installation view, Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, courtesy of the artist.

22. Fari Shams, Paradise in a square, 2016, film still, Summer Wars (2009), courtesy of the artist.

One tool we have thus to resist predictability and to classify while not pigeonholing, is the atlas or any kind of montage in the sense that they imply infinite juxtapositions. Making comparisons helps defying – yet not abolishing – borders by extracting elements from their assigned context to consider them as equivalent, by ‘understand[ing] things as birds we would prefer not to immobilise in a too conventional use, the cage of our language and of our thinking categories’.32 The uprightness of the squares we use to demarcate organize reality is necessarily threatened by the fields nearby. The surge in the use of atlas-like forms in art as well as scholarship leads some to believe that it could be the hermeneutic key to the current overwhelming profusion of images we now confront. However, one should be careful in using both these devices insofar as they mostly rely on a questionable faith in the virtues of what Philippe-Alain Michaud referred to as ‘theoretical fictions’.33 As Yve-Alain Bois has recently argued, juxtapositions cannot be forgetful of origins, otherwise they run the risk of becoming what he terms ‘pseudomorphosis’ illusion. This is the idea that two works can speak to each other simply because they have similar external features – for instance an abstract painting of Kenneth Noland and a ceremonial shield from Papua New Guinea.34 If Fari Shams emphasizes the pigeonholing inherent in the various modes of representation, the denial of whole categories does not propose a better alternative than the obsession for compartmentalizing. She reminds the viewer on the one hand that the shapes we use to organise and re-present reality have histories themselves and cannot be taken for granted. On the other hand, however, she is insisting with the orchestration of her installation that there is no one way of looking. It is precisely between the spaces and gaps of the different trajectories included in this work that she would like the process of looking to start. The increase of speed and the increase of data do not necessarily improve our modes of representation.

Any map is the combination of names whose origin is located at times in privacy, at times in history, but doomed to be absorbed through time as pure signification, as exemplified with the Antarctic. Naming is a paradoxical gesture of appropriation in the sense that it denies the possibility for a noun to remain proper. Systems of representation, maps and metaphors are alike in their capacity to reduce exoticism to a limited vocabulary. Paradise in a square is precisely a vertical reading, a consideration of the ‘thickness’ of representations and narratives, which help to look at words and images just as the icebergs through which Jean Batiste Charcot was sailing: liable to turn over from time to time and expose their hidden parts.

Acknowledgements:

The author is grateful to Fari Shams for her continuous and helpful attention, as well as to James Tierney at the Yale Center for Language Study for his invaluable proofreading.

1. See the article in Le Point, 04/18/2015, http://www.lepoint.fr/politique/corbeil-essonnes-une-avenue-serge-dassault-remplace ra-le-boulevard-jaures-18-04-2015-1922491_20.php.

2. See Pierre Escudé in Jean-Baptiste Charcot, Le Français au Pôle Sud [1906] (Paris: José Corti, 2006), 328.

3. Wolfgang Iser, L’Appel du texte [1969], trans. V. Platini (Paris: Allia, 2012), 47 et passim.

4. Henry Fielding, The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews [1742] (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987), 70.

5. Thomas Herbert, Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Africa and Asia the Great. Describing more Particularly the Empires of Persia and Industan (London, 1677), 12.

6. Charcot, Le Français au Pôle Sud, 80–81.

7. Hans Blumenberg, Naufrage avec spectateur, trans. L. Cassagnau, (Paris: L’Arche, 1994), 30.

8. Charcot, Le Français au Pôle Sud, 307.

9. Idem, 318.

10. Georges-Didi Huberman, Invention de l’hystérie [1982] (Paris: Macula, 2012), 38; trans. A. Hartz (Cambridge (Mass.): The MIT Press, 2003), 19.

11. Idem, 20, 4.

12. « 16 avril 1904 » in Charcot, Le Français au Pôle Sud, 146–47.

13. Michel Foucault, ‘Des espaces autres,’ in Dits et écrits II. 1976-1988 (Paris, Gallimard, 2001), 1571–81

14. Idem, 1578.

15. Saint-Simon, Mémoires (Paris: Gallimard, coll. La Pléiade, t. V), 532.

16. René-Louis de Girardin, De la composition des paysages sur le terrain ou des moyens d’embellir la nature près des habitations en y joignant l’agréable à l’utile (Genève: M. Delaguette, 1777), IX–XX.

17. Antoine-Joseph Dezallier d’Argenville, La Théorie et la pratique du jardinage, où l’on traite à fond des beaux jardins, appelés communément jardins de propreté (Paris: J. Mariette, 1709), 66.

18. This expression, which is now used colloquially to designate the particular domain or the proper field pertaining someone, finds its origin in a letter Vauban addressed to Louvois, the secretary of State in charge of war, on January 19, 1673 in which he claimed that the king ‘should think of making his pré carré’, meaning that he should secure the Northern border of French kingdom.

19. Bertolt Brecht, Über die Gewalt, in Gedichte V., 1934–1941 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1978), 103.

20. See Nikola Jankovic, Trois zoos humains (Paris: Éditions B2, 2012), 28–40.

21. Idem, 43.

22. Emmanuel Pernoud, Paradis ordinaires. L’artiste au jardin public (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2013), 27.

23. Fari Shams, commentary within Paradise in a square.

24. Didi-Huberman, Atlas ou le gai savoir inquiet (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2011), 13. [‘Worried knowledge’ is often translated as ‘anxious (gay) science’ – OAR Editors]

25. I warmly thank the author for use of quotes in advance of publication.

26. Jean-Paul Sartre, Situations II (Paris: Gallimard, 1948), 64.

27. Foucault, 1571–72

28. Richard Leppert, The Sight of Sound: Music, Representation, and the History of the Body (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 35.

29. Didi-Huberman, 20.

30. Aby Warburg, L’Atlas Mnémosyne (Paris: L’Écarquillé, 2012), 64.

31. Warburg, ‘A Lecture on Serpent Rituel,’ trans. W. F. Mainland, Journal of the Warburg Institute 2:4 (1939): 292.

32. Didi-Huberman, Atlas ou le gai savoir inquiet, 110.

33. Philippe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg et l’image en mouvement (Paris: Macula, 2d ed. 2012), 7.

34. Yve-Alain Bois, ‘On the Uses and Abuses of Look-Alikes,’ October 154 (2015): 127–149.