Acquired Tastes: Experiments in Campus-Based Art Museums

Derrick R. Cartwright

To cite this contribution:

Cartwright, Derrick R. ‘Acquired Tastes: Experiments in Campus-Based Art Museums.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/acquired-tastes-experiments-campus-based-art-museums/.

We have to accept the fact that basic research, whether in the sciences or arts and humanities, is inherently risk-taking; its outcome cannot be determined in advance if its methods are to be valid.

– James Cuno1

Appreciation for museum labor and its attendant pleasures is elusive. My own first experience working in an art museum came while still an undergraduate. For a few hours each week, I was stationed behind a large desk within the main entry of what was then known as the University Art Museum, a Mario Ciampi-designed, Brutalist building that bordered one edge of the UC Berkeley campus.2 Essentially, my role was to inform those who walked into the vast, concrete facility where they could safely store their backpacks, explain where the café, bookstore, auditorium, and restrooms were located, and sell tickets to the non-student, non-faculty visitors, of which there were typically few. I did not last long in that function. That impatience can be attributed more to my own still-evolving sense of what might actually make for satisfying work than to any fault of the museum. Still, the volunteer job provided me with a lasting empathy for the discomfort that the public often feels while waiting for such places to reveal themselves. Standing at the periphery, even an enthusiastic art history student might strain to imagine what could ever fill a museum career with wonder, much less a sense of purpose.

In fact, most museums conceal their basic decision-making and research missions from outsiders. While it has, in recent years, become commonplace for museums to offer glimpses into conservation practices, to provide more than one interpretation of an object on accompanying labels, or to encourage selfie-taking in their galleries, few of these laudatory efforts to promote ‘participation’ reach the level of real demystification. Visitors may still ask: ‘What do the curators do all day?’; ‘Can it really be a full-time job to move an object six inches to the right, or left, so it gets seen to greater advantage?’; ‘Are things in the basement ever going to see the light of day?’; or, ‘What happens here when the public is not?’. In spite, or perhaps because of the opacity surrounding my own initiation to the business of museums, when given opportunities to lead museums myself, I have pursued more or less direct efforts to act against these, and other, false impressions. As a director of two campus-based museums, I have been interested in ways to examine the decision-making of museum professionals for the students with whom I am privileged to work, and to engage them in these non-profits’ most compelling practical and ethical issues. Once day-to-day matters are exposed and made essential, new scholars become more curious about the ways that work gets conducted in and through these complex institutions.

Exhibition practice can be used as a chance to increase understanding of what is at stake in such validating situations. At Dartmouth College, a museum has been part of campus life since 1772. The Hood Museum of Art, where I was director from 2000 to 2003, began a serious expansion of its teaching objectives when it invited undergraduates to develop ownership of a curatorial series. A prominent space within Charles Moore’s postmodern lobby space had been unloved by the curators on staff almost since the day the building opened in 1985. A quirky conjunction of walls on either side of an elevator cried out for attention. Starting in 2001, undergraduate interns were asked to curate this space as part of their museum experience. Few instructions accompanied the basic assignment: displays were to be selected from the Hood’s permanent collection of more than 60,000 objects, each intern had to participate by working alongside the professional staff charged with the installation duties, and the works ought to mean something to the student, both personally and as part of a larger community of scholars on campus. Thanks to generous alumni, each intern was also given the chance to publish their ideas in an accompanying brochure. They were further encouraged to discuss their choices publicly as part of regular museum programming. From the outset, A Space for Dialogue earned a status as something paradigmatic among teaching museums and has been suggested as a model program.3 The fact that the series continues to be seen as an effective strategy for engaging students in the Hood’s practice and that it has been widely emulated beyond Dartmouth suggests at least this much.

While it might be gratifying to reflect on a single, successful innovation, especially in contrast to my own early introduction to museum work at Berkeley, it is worth recalling how risky Space for Dialogue experiments seemed to many when first proposed. They required a certain leap of faith on the part of stakeholders who wondered aloud whether it was right to expect students to rise uniformly to the challenge of re-interpreting these historic collections. Others feared that the decisions these scholars would make might somehow reflect badly on the institution as a whole. These ended up being short-lived concerns. Few, if any, student curators chose to point their projects toward narrowly self-serving themes, and most observers quickly grasped that the student perspectives, while distinct from those of the professional staff, were thoughtful, well researched, and aspired to be taken as seriously as anything else that took place in the Hood. If failing to live up to the high standards of a model college art museum was a worry at the outset, the steady audience of visitors who came to hear the curators speak about what they had done represented at least one measure of their collective success. The early projects I witnessed in the series uniformly engaged with professional concerns of curation with solemnity. Collectively, these projects validated the initial experiment and showed skeptics how much new knowledge could be generated by taking seriously the idea of ‘fresh perspectives’ as an innovative tool. Now moving steadily toward its 100th iteration, the students routinely bring the full force of their highly individual approaches to bear on the Space for Dialogue series and, in turn, shape the museum’s reputation for thoughtful interpretive work. (Figure 1) The debates inaugurated in this modest space seem vital and inspire campus debates beyond the museum itself. For example, during a period of building renovation, students otherwise deprived of physical space turned to virtual displays to catalyze discussion of sculpture displays throughout the campus.4 Most importantly, this precedent of exhibitions successfully curated by students catalyzed still bolder risk-taking within the museum community at large.

A Space for Dialogue # 86. Emblem: Figuring the Abstract in Social Commentary, Bay Lauris Byrne Sim ’15, Mellon Special Project Intern, courtesy of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, pholograph by Jeffery Nintzel.

Collecting art on college campuses is a privileged process, determined by each institution’s unique competencies and by the prerogatives of its credentialed staff.5 Students are by and large excluded from making decisions about acquisitions because it is assumed that their relative inexperience disqualifies them from the responsibility to spend museum money wisely, or because they have yet to connect the various forms of knowledge – history, conservation, ethics, markets, and connoisseurship, etc. – required of those who steward the growth of museum collections. Add to this the fact that most institutions struggle to find the resources needed to finance an ambitious acquisitions program, and it is easy to justify the professional inclination to exclude students from this solemn, costly endeavor. With few exceptions, this has meant that teaching collections seldom bother to ‘teach’ collecting in a ‘hands-on’ way.6

Against elitist protocols, I would argue that many students possess their own useful skepticism about the ways that art museums confer status on objects. I’ve found that the undergraduates I teach are blissfully unimpressed by names taken from canonical texts or from the pages of contemporary art journals. As emerging scholars, they are sometimes perhaps more apt to be influenced by specific narratives that relate to their own lives than they are by the writings of mainstream art historians, but whether or not this is the case, it need not be considered a shortcoming. Even the most risk-averse students tend to know what they like and value about visual culture. Steeped in cultural studies and immersed in visual culture through hours spent observing on-line, the predominantly twenty-somethings that form the largest part of these undergraduate bodies are well-informed about contemporary representational methods and politics. While this is also an inherently diverse community of scholars, they share the tendency to consume fresh images with confidence, and circulate them as a matter of routine. They critique, cherish and discard representations with equal relish. This is just to say that they tend to look at art quite differently than I do and bring different criteria to its validation as a result.

Starting in 2003, the Hood’s talented Curator of Academic Programming, Katherine Hart, and I began teaching a course to Dartmouth undergraduates on ‘How Museums Collect Art’.7 The culminating experience of that after-hours, non-credit course was the group acquisition of a photograph for the museum’s permanent collection.8 Staff and students met weekly during the term to debate the mission of a campus museum, study gaps in its collection, ponder the ethics of acquisitions, and research the current market for photography. Freed from the responsibility of raising funds for the acquisition of objects at a campus-based museum, would they choose differently than credentialed professionals? That is the question asked in that academic context, and once since, and that I would like to turn to now in the space of this contribution to OAR’s discussion of validity.

Asking students to participate directly in acquisitions selection, rather than passively as viewers of what others had acquired on their behalf, does something more than merely flip the usual, unspoken power dynamics of museum spectatorship. It also offers up the possibility of opening an entirely new vein of collections history. In campus-based museums (as well as at many larger civic institutions), works of art typically arrive as gifts of contemporary supporters (often alumni), as part of bequests, or as the result of individual curatorial drive. In the 21st century, only in the most privileged situations are major acquisitions made as part of something like a pre-defined strategy for a collection’s use and study. By carving out space for student acquisitions as a subset of the overall permanent collection, the Hood created the chance for something like a longitudinal study of ‘undergraduate collecting preferences’ within a specific institutional framework, the first analysis of which will be sketched briefly here.

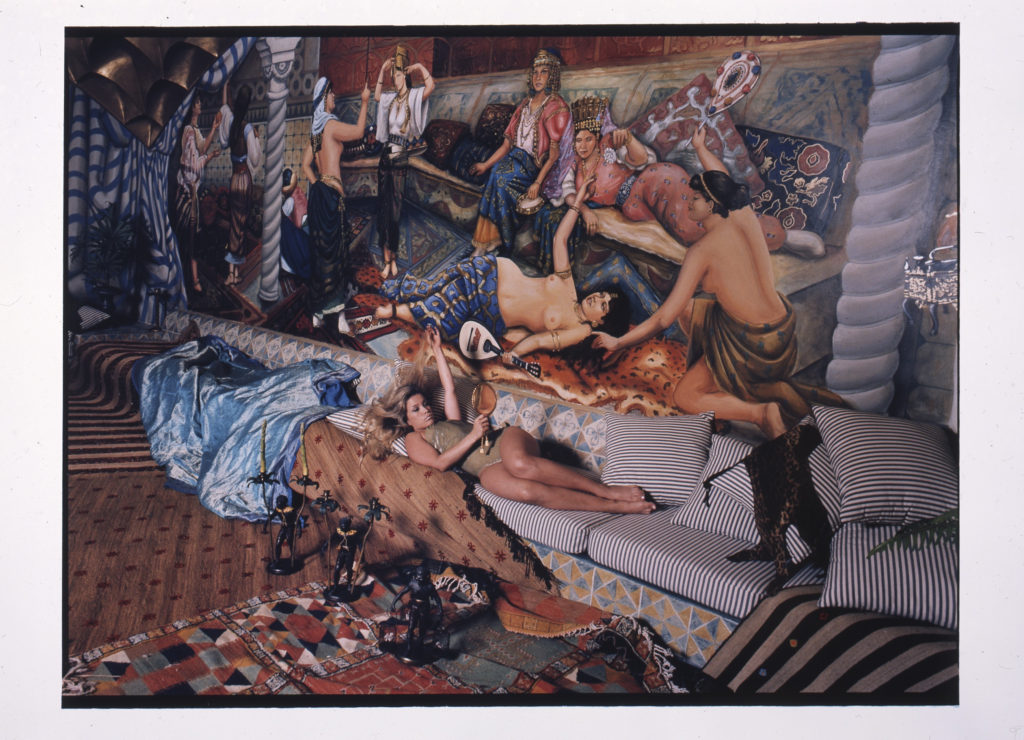

Sixteen photographs, so far, have entered the permanent collections at Dartmouth through this particular experimental mechanism. The museum describes the fruits of this student collecting in highly positive terms: ‘The result has been the addition an array of phenomenal photographs, including Daniela Rosell’s Untitled (Janita Harem Room, Villa Arabesque, Acapulco, Mexico) . . . , (Figure 2) Loretta Lux’s The Drummer . . ., Ogle Winston Link’s Hawiksbill Creek Swimming Hole. . . , Nobuyoshi Araki’s Untitled, “Bondage (Kinbaku),” Sebasatião Salgado’s Brasil (Hand, Serra Pelada), and Mario Cravo Neto’s Christian with Bird’.9 But, beyond this praise, what might be said about the photographs as a self-defined group of works, or the ways that they might be seen to validate a museum’s inclusion of a community of predominantly young people, admittedly advantaged, but positioned outside of professional museum culture?

Daniela Rossell, Untitled (Janita Harem Room, Villa Arabesque, Acapulco, Mexico) from Ricas y Famosas, 2001, Chromogenic Print, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, purchased through gifts from Charles W. Gailard, Class of 1963, Kenneth I. Reich, Class of 1960, James and Susan Wright, Lee and Marguerite Berlin, Karen Berlin, Class of 1989, Elizabeth Craig, Class of 1944W, Jan Seidler Ramirez, Class of 1973, and the Class of 1952, selected by participants in the seminar ‘Museum Collecting 101’: Sarah Bohlman, Class of 2004, Jeffrey Cooperman, Class of 2006, Joan Kim, Class of 2005, Amy Kurtz, Class of 2006, Sarah Murray, Class of 2004, Rolaine Ossman, Class of 2004, Arielle Ring, Class of 2007, Catherine Robert, Class of 2005, Emily Salas, Class of 2006, Liz Seru, Class of 2004, Eleanor Smith, Class of 2004, Miell Y. Yi, Class of 2002; PH.2004.18. © Daniela Rosell.

Before responding to that question directly, let me submit a second, demographically distinct sample for consideration. I began a similar experiment in collecting with undergraduates at the University of San Diego in 2012. A quick glance at a map will illustrate that San Diego, California is nearly as far away from Hanover, Hampshire as one can travel in the United States. Located less than a half hour from a busy international border with Mexico, the surrounding culture is diverse and urban. San Diego is the eighth largest city in the United States; Hanover has a population of just over 11,000 residents. In terms of their respective campus cultures, USD and Dartmouth College, differ in equally significant ways as well. USD is a young-ish, (chartered in 1949), private, Roman Catholic institution, and Dartmouth (founded in 1769), is based in Calvinist/Congregationalist theology, but for more than a century has operated as a wholly secularized institution. Both schools pride themselves on the quality of academic instruction they provide to a fairly shallow pool of students. Dartmouth’s centuries-old reputation and high selectivity (4300 undergraduates as opposed to 5700 at USD), and its enviable financial resources, leads to its higher ranking among national universities in the U.S.10

Another differentiating factor between USD and Dartmouth is the absence of an ‘encyclopedic’ museum on the campus in San Diego. Instead of a stand-alone, landmark piece of architecture, such as the Hood, USD has six small galleries scattered throughout its 180-acre campus, together with a well-equipped study/storage facility that doubles as a library, called the Hoehn Print Study Room. That small space houses a growing collection of original prints. When I arrived in 2012, I convinced a local foundation to fund an endowment, the proceeds from which would enable undergraduates to purchase prints for the University. The Legler Benbough Student Acquisitions Endowment currently yields several thousand dollars per year for student purchases that are themselves a product of class assignments, integrated into several undergraduate art history courses in the Department of Art, Architecture + Art History, where I now teach.

This second student collecting experiment has been adapted to the different circumstances of the academic environment at USD. Original prints, not photographs, better match the mission of the program at this relatively new institution that lacks adequate space for storing large-scale painting or sculpture. Additionally, because this project grows out of syllabi from a limited number of for-credit course offerings, in the course I teach most often called ‘Collections, Collecting, Collectors: History, Theory, Madness’, the participants are not necessarily art history majors. Indeed, a significant number of the undergraduates who gain a fleeting appreciation for curatorship, and its attendant concerns, come from outside of the College of Arts and Sciences entirely. They include majors in Business Administration, Education, or Peace Studies programs, and they bring with them the perspectives they have learned in those disciplines outside of the Humanities. Finally, the fact that this selection assignment is given to groups who present their choices for a grade, as opposed to the voluntary/consensus model pursued in the Hood’s Museum Collecting 101 course, shapes the selection process as a form of competition.

It needs to be stressed that students today already possess a vocabulary drawn from museology. Many speak casually of ‘curating’ their lifestyles through musical playlists and other media preferences.11 While many profess a preference for uncluttered minimalism in their own personal environments, when asked to work in small groups as part of a curatorial team, they utilize certain maximalist presumptions about their age group’s preferences and preoccupations. Large scale, colorful work is an attractor and ‘in-your-face’ political ideology is quite often admired above aesthetic restraint, or conceptual coolness. Reviewing eight acquisitions acquired through the courses utilizing a student acquisition assignment since 2013, one is struck by the strong, if diverse, political and philosophical commitments of the imagery and the artists who produced it: Shahzia Sikander, Orbit II (2012) (Figure 3); Gary Simmons, Starlite Theatre (2012); Liset Castillo, Rice (2000); Corita Kent, news of the week (1969); Robert Rauschenberg, Support (1973); Mel Bochner, Blah, Blah, Blah (2014); Helen Zughaib, Changing Perceptions, Abaya 1-3 (2009); and June Wayne, The Bride (1951).12

I am, it hardly needs to be said, always a fan of these students’ choices, though not all of them would have been my own. The fact that these scholars tend to identify work by women and artists who have been historically underrepresented in American museum collections could be viewed, perhaps negatively, as evidence of political correctness. However, my students’ deliberateness about adding the first works by Muslim women artists to USD collections has been a source of inspiration to me. Most of their choices tend to be contemporary, as opposed to ‘Old Master’ selections. I prefer to consider these as indexes of the students’ fearless embrace of the changing intellectual stakes in campus-based museums. At both Dartmouth and USD, students know that their names will be associated with the works they select as part of credit lines that appear in object records and labels. In this way, their temporary experiment in curating is guaranteed a permanent place in the institutional history of these collections. In contrast to ephemeral curatorial practices – the pop up exhibition housed in an alternative space comes to mind – these objects are destined to remain on site for use, re-use, and future scrutiny. Their very status as ‘student selected’ identifies these works as categorically different, and suggests that they be meaningfully compared to the larger institutional collections that surround them. I am interested in the contrasts that might emerge from such comparison and their potential validity as case studies within a changing museological frame. At this point, the sample of works seems statistically too slight to come up with a clear picture of what this difference may ultimately mean. Still, a few generalizations might be suggested both as a summary of what has been observed and as a way to conclude this brief essay.

Shahzia Sikander, Orbit, 2012, color direct gravure, 27 x 21 ¼ inches, Print Collection, University of San Diego, purchased through the Legler Benbough Student Acquisition Fund by Katherine Ayd, Jerome Bwire, Cesar Chavez, Virginia da Rosa, Hannah Day, Ross Ehren, Brittany Ford, Anthony Graham, Dominique Kourie, Morgan Likens, Monika Marambio, Liam Richards, Sean Rivera, Joseph Seiler and Jake Zawlacki, cour test of Crown Point Press, San Francisco, CA.

When arguing for the acquisition of a particular work, students are often passionate and resort to claims based in value judgments of the sort not likely to be heard in museum boardrooms: ‘This print by Barbara Kruger is awesome and we think it would be really cool to add it to our collection’, for example, was something I heard in the course of a recent student presentation. The statement is not necessarily naïve. Such unconcealed presentism might alarm some professional curators but is nonetheless instructive for museum professionals to consider this perspective as grounded in an intellectual concern for preserving representations of current import. From the student’s vantage, the world of collections has never been free of subjective judgment and ought to be more fully charged with their enlivened, contemporary sensibility – with an appreciation for what makes a thing ‘awesome’ to the everyday viewer. It also needs to be said that in classes made up of a broad spectrum of majors, there have been diverse responses to the task of convincing others to pay attention to a particular work by a particular artist that might have more obvious value to one discipline or another. When an undergraduate argues that they are moved by an image and think it could become an enduringly useful teaching object, they provide more than just their own limited evaluation; they also represent a class of users who will foreseeably address this same work of art with similar commitments and enthusiasm. Those of us charged with stewarding collections on behalf of those users would do well to listen.

‘Our bias against the validity of subjective responses to art may be based on the assumption that relevant statements concerning any discipline must share the capability of being publicly verifiable’, argues N. Blaine Kauffman’.13 That verification needn’t wait long. The growing collections of student-selected work at both Dartmouth College and at USD represent an experimental body of evidence that is opening now to this secondary evaluation. Works selected through these experimental research methods will soon appear more nuanced, I predict, and, in time, those of us charged with stewarding those collections will better recognize the separate risk-taking commitments they reflect. In this regard, these acquisitions will come to resemble so many others studied in our museums, even as they can’t help but reveal their separate origins to those who study their history. Works of art proposed by undergraduates as valid for teaching purposes end up standing significantly apart, permanently demystifying the process of acquisition for all interested enough to take notice and empowering those who strive to engage in these spaces with deep purpose and inclusivity.

1. James Cuno, ‘Defining the Mission of the Academic Art Museum,’ Occasional Papers: Harvard University Art Museums (1994): 17.

2. The University Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive opened in 1970, but was deemed ‘seismically unsafe’ in 1997, at which time plans to re-build the institution at a new location were announced. The Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMFA) opened to the public in January 2016 in downtown Berkeley, approximately ten blocks away from the former building’s site.

3. For a critical discussion of this program in the context of campus museums in the United States, see: Janet Marstine, ‘What A Mess!: Claiming a Space for Undergraduate Student Experimentation in the University Museum,’ Museum Management and Curatorship 22 (2007): 303–15. The Space for Dialogue experiment now in its 92nd iteration continues at the Hood to the present moment, although facility expansion has temporarily interrupted the series.

4. See: ‘Hood Interns Make Virtual Exhibitions,’ Dartmouth News (11 May 2017), accessed 7 October, 2017, at https://news. dartmouth.edu/news/2017/05/hood-interns-make-virtual-exhibitions.

5. As an example of an articulate dialogue surrounding the difference in campus-based acquisition strategies, see: ‘To Serve the Common Good: The Grinnell College Art Collection,’ Art in Print 7 (2017): 18–23.

6. One early, notable exception might be the so-called ‘Museum Course’ taught by Paul J. Sachs, Associate Director of the Fogg Art Museum, at Harvard University during, roughly, 1921–47. This legendary course was among the first to integrate museum practice and theory so that the students who took Sachs’s course also learned how objects became part of the permanent collections at the Fogg, participating to a limited degree in the selection process. Student notes detailing the course’s premises are today included in the Paul J. Sachs Papers located in the Harvard Art Museum Archives, Cambridge, MA. For a guide to their contents, see: http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~art00010. Other schools have, after Dartmouth, adopted this model. Stanford University, for example, offers a course called ‘Collecting for the Cantor’, as part of its curriculum: https://art. stanford.edu/courses/2016-2017-arthist-216.

7. For a description of the current course offering, see: http://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/learn/dartmouth-students/museumcollecting- 101.

8. Photography was chosen for two reasons: (1) the Hood did not have a curator charged with responsibility for this medium (and therefore no one on staff could argue that their professional responsibilities were being abridged by students), and (2) the otherwise sprawling collections at Dartmouth was weak when it came to photography. Hart is now Senior Curator of Collections, as well as the Barbara C. and Harvey P. Hood Curator of Academic Programming for the museum. I thank her for sharing with me her subsequent experiences in ‘Museum Collecting 101’, as the course is now more popularly known.

9. E. S. Burke, ‘Photographs,’ in Modern and Contemporary Art at Dartmouth: Highlights from the Hood Museum of Art, ed. Brian Kennedy and Emily Shubert Burke (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2009), 194. In addition to the six works mentioned within the quote, the following photographs were also purchased by classes of students since 2009: Daniel Beltra, Alter Do Chan, Para (Brasil) (2005); Atta Kim, Museum Project #004, from the Field Series (1996); J. Henry Fair, Arsenic and Water (2009); Ian Teh, Kuye River, Yulin, Shaanxi from the series Traces (2010/12); Tierney Gearon, Untitled from the series The Mother Project (2001); James Karales, Selma to Montgomery March (1965); Maria Macilau, Untitled (Living on the Edge Series) (2014); Mishka Henner, Staphorst Ammunition Depot, Overijssel from the Dutch Landscape Series (2011); Jerome Liebling, May Day, Union Square Park, New York City (1948); and, Doug Rickard, #40.805716, Bronx New York (2007). Additionally, eight ‘second choice’ photographs have been purchased as a result of additional funds, and one etching, Jules de Bruycker, Fetes Populaires, Bruxelles (1928), was acquired when the Museum Collecting 101 course was taught by a curator other than Hart.

10. According to the US News and World Report’s 2017 ranking system, Dartmouth is judged #11 among National Universities while USD is assessed the rank of #86 in the same category. See: https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-liberalarts- colleges?_mode=list.

11. A superficial scan of internet sources suggests that ‘curating’ one’s personal life had risen to common parlance sometime before 2012. Since that time, critical writing in the United States has vacillated between treating this broadening usage as a symptom of mindless cultural appropriation or, alternatively, viewing it as evidence that digital media empowered individualism. See: Miya Tokumitsu, ‘The Politics of the Curation Craze,’ New Republic (15 August 2015), accessed 7 October, 2017, at https://newrepublic.com/article/122589/when-did-we-all-become-curators. Multiple layers of the ‘curated self’ are identified and discussed in David Michael Kasch, ‘Social Media Selves: Curation of the Self and Others through Facebook,’ Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 2013, esp. 90–147. For a summary of academic writing on the topic, see ‘Everyone Is a Curator,’ JSTOR Daily (29 March 2016): https://daily.jstor.org/everyones-a-curator-jstor-daily-reads-the-news/ .

12. Additionally, as revealed at Dartmouth, student passion served to generate unexpected support for the acquisition of other works they proposed. In the case of USD, the following prints were acquired as more or less direct results of student research and interest: Fred Wilson, Arise! (2004); Ana María Hernando, El Corazon Innocente (2010); Tiago Gualberto, Pay Per Doll I (2012); Enrique Chagoya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters from Recurrent Goya (2012); and Corita Kent, let the sun shine (1968).

13. See N. Blaine Kauffman, ‘The Validity of Personal Response,’ The Journal of Aesthetic Education 12 (1978): 100.