The Lives and Deaths of Inhabitants in Abandoned Houses

Gregory Buchakjian

To cite this contribution:

Buchakjian, Gregory. ‘The Lives and Deaths of Inhabitants in Abandoned Houses.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/lives-deaths-inhabitants-abandoned-houses/.

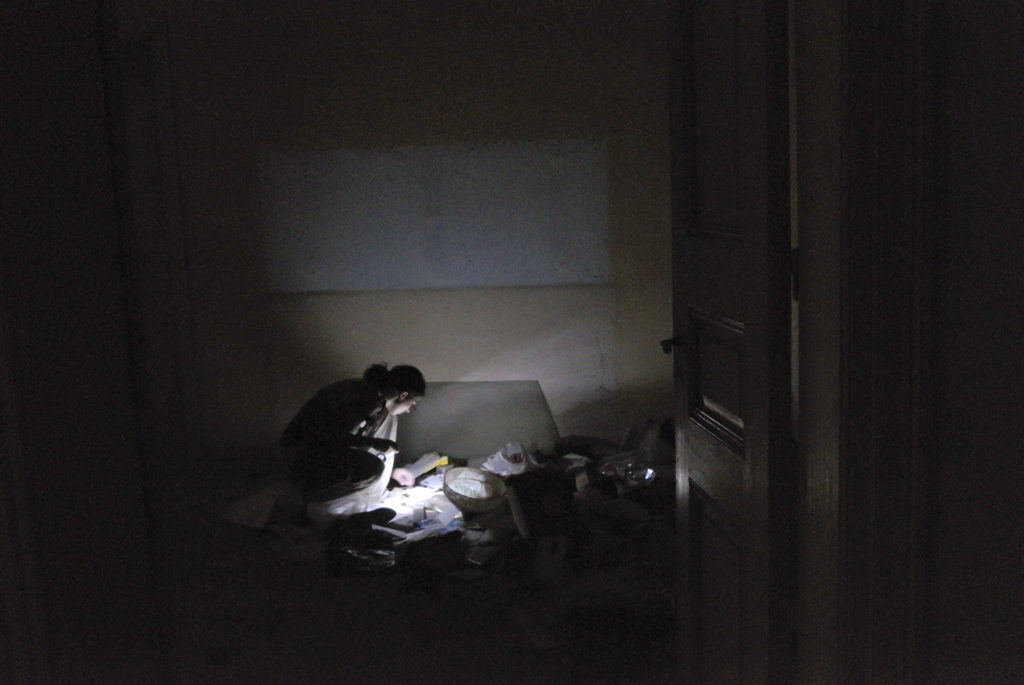

Gregory Buchakjian, Maya Akiki in the central hall of Victoria K.’s former apartment, 2015, digital photograph.

The truth is somewhere between the documentary and the fictional, and that is what I try to show. What is real one moment has become imaginary in the next.

– Robert Frank

Preamble: Fiction and Truth in Post-War Lebanon Art Practices

In July 1998, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige displayed a series of burnt postcards then titled Beirut, Urban Fictions, known later as Wonder Beirut, the Story of the Pyromaniac Photographer.1 According to their statement, the Lebanese Tourism Agency had in 1968 commissioned the so-called ‘Studio Wahed’ to shoot postcards of Beirut. When war spread in 1975, Studio Wahed was destroyed. One of its members, Abdallah Farah,

succeeded in rescuing some material – a fraction of his negatives, including those of the postcards…Three years after the start of the war, he began to damage his postcards, burning them little by little – an intentional process of deterioration – as if seeking a way to have their states conform to his present. He imitated the destruction of the buildings, which were progressively disappearing before his eyes.2

In 2001, after Jalal Toufic asked Hadjithomas and Joreige for clarifications, they conducted an interview with a journalist named Pierre Menard. Menard proclaimed that ‘by photographing these images you invented a new path, that of deliberate anachronism and wrong techniques’.3 Meanwhile, also in 2001, Hadjithomas and Joreige stumbled across the belongings of Alfred Kettaneh, Khalil’s uncle who was kidnapped in 1985 and was reported missing. Among the things found was a Super-8 ‘latent’ film, undeveloped. After much hesitation, they sent it to the lab.

The film came out veiled and white, with a barely noticeable presence that vanished immediately from the screen. We searched within the layers of the film itself, attempting to create the reappearance of a presence, of lasting images.4

In 2004, Hal Foster proposed the idea of an ‘archival impulse’ in modern and contemporary art, where ‘in the first instance archival artists seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present’.5 This idea had particular resonances in Lebanon, where the absence of a collective narrative led to an unofficial ‘memory culture’, one ‘generated by civil society, political groups, and nongovernmental agents including artists, novelists, investigative journalists, academics and filmmakers’.6 In 1997, the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) was established with the mission ‘to collect, preserve and study photographs from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora’.7 In July 1999, speaking at a colloquium,8 Walid Raad revealed the existence of the Atlas Group, an institution seeking to ‘locate, preserve, study, and produce audio, visual literary and other artifacts that shed light on the contemporary history of Lebanon’.9 These proposals empowered intersections between artistic practice and the research of historians, archaeologists and archivists. For instance, AIF cofounder Akram Zaatari began in 1999 a long-term collaboration with Hashem el-Madani, a portrait photographer from Saida.10 He produced a body of work composed of books, exhibitions and videos that undoubtedly generated invaluable knowledge, on Madani in particular, and on studio photography in general. The project was done under the auspices of the AIF, which guaranteed its seriousness and legitimacy. However, Zaarari affirmed – and this applies to his entire oeuvre – that ‘I see my motivation for research not as that of the historian but an artist interested in history’.11 Disclaiming himself from being a scholar, Zaatari was implying that the artist could work in parallel – or even in competition – with the scholar.

The ambiguities surrounding these artists’ attitudes towards their disciplinary affiliations were present in their work. Were we being led to view photographs by Madani and Farah as historical documents, or their reinvention by Zaatari and Hadjithomas and Joreige as contemporary artworks, where, as Zaatari writes ‘photography is a subject, before it is a medium’?12 Furthermore, it came into sight that the ‘postwar generation has come to be known for a more archival approach that enacts disciplinary border crossings between fictional and historical narration’.13 While Madani is as real as his studio, much has been said about the contradictions concerning the contents of the Atlas Group and its existence. In the early 2000s, Raad admitted:

In different places and at different times I have called the Atlas Group an imaginary foundation, a foundation I established in 1976, and a foundation established in 1976 by Maha Traboulsi. In Lebanon in 1999, I stated, ‘The Atlas Group is a nonprofit foundation established in Beirut in 1967’. In New York in 2000 and in Beirut in 2002, I stated, ‘The Atlas Group is an imaginary foundation that I established in 1999’.14

No less intriguing were Hadjithomas and Joreige’s positions. In Wonder Beirut (1997–2006), they attributed existing touristic postcards to a fictional photographer, and simulated an interview with a fictional journalist whose name was notably borrowed from ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’, a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, where the character expressed the intention to rewrite Miguel de Cervantes’ masterpiece, neither through transcription nor copying, but in producing pages that would coincide word by word with the original. Then, in Lasting Images (2003), Hadjithomas and Joreige developed the film of Kettaneh who effectively disappeared while driving a Red Cross ambulance. In Foster’s estimation of archival art generally, he writes how ‘the work in question is archival since it not only draws on informal archives but produces them as well, and does so in a way that underscores the nature of all archival materials as found yet constructed, factual yet fictive, public yet private’.15 Such border-crossings between reality and the imaginary were what Carrie Lambert-Beatty termed ‘parafiction’. Citing, among other examples, Walid Raad’s Hostage: The Bachar Tapes (#17 and 31)_English Version, presented as a testimonial by former hostage Souheil Bachar who allegedly, after his release ‘collaborated with the Atlas Group to produce 53 videotapes about his captivity’,16 Lambert-Beatty explains:

Unlike historical fiction’s fact-based but imagined worlds, in parafiction real and/or imaginary personages and stories intersect with the world as it is being lived. Post-simulacral, parafictional strategies are oriented less toward the disappearance of the real than toward the pragmatics of trust. Simply put, with various degrees of success, for various durations, and for various purposes, these fictions are experienced as fact.17

Coming under Michel Foucault’s historical a priori, as ‘not a condition of validity for judgements, but a condition of reality for statements’,18 these practices were defying Lebanon’s politics of amnesia. Lasting Images, for example, was materializing the resurgence of one of the thousands of disappeared. As Waled Sadek says, ‘It is in producing the disappeared as an excess object in absentia, as here rather than elsewhere, that awaiters step out from the margins and begin the labor of conversing with the disappeared that charges absence with uncanniness’.19 This may explain the abundancy of ghosts and vampires in Lebanese art, literature and cinema, notably the films of Ghassan Salhab and the writings of Jalal Toufic. We decided to let them say, ‘we are convinced’ twice, a series of photographs shot during the 1982 Siege of Beirut, as part of the Atlas Group, strangely contains scratches and stains. In a mail conversation, the artist questioned what led to this phenomenon:

Did I place them there to emphasize the distance that separates me from these events in 1982, 24 years earlier? No. Are they meant to represent the present but non-imaged traces of fire that littered the sky and city that summer? Do they represent my inability to see the event fully, the result of some psychic shock or physical scotoma? No. Are they meant to emphasize the medium itself, the mediating qualities of the photographic surface? No. I have always felt that the scratches, thumbprints, and color stains actually belonged to the world, and not to my prints nor negatives. In other words, it is the world itself that was scratched and stained, and I recorded it as I saw it. As a classically trained photographer, I take very good care of my negatives and prints. My negatives are intact. They did not decay with the passage of time. The scratches are not on my prints, and negatives but in my images… As such, I wonder whether in the summer of 1982, I was actually photographing reality as photographic.20

The traumas and ghosts rooted underneath these artworks have equally nourished my practice that also comprises an imbrication of traces, documents, testimonies and autobiographical memories, whose validity may equally be questionable. One story sheds light on the drifting between real account and fable. It took place during the summer of 1975, when fighting was sporadic and talked about as ‘the events’ rather than ‘war’: My father, Sarkis Buchakjian, and I – I was four years old – were driving on the airport road. Palestinian warriors intercepted the car and abducted us. We were taken to the camp of Chatila, and held for approximately six hours before being released. In 2015, my father confessed the airport road incident didn’t happen as we were told for forty years. According to his new version, a military vehicle slightly hit our car on a ride back from the airport. My father, who was still accustomed to living in a ‘normal’ country, required reparations. The militiamen answered that we should see their chiefs. They lead us inside the camp. Upon our arrival, a parade was taking place, and all were busy. It took hours for my father to meet someone. He received apologies, but no financial compensation. On his way home, my father, in an act of conscience over the recklessness of the gesture which may have jeopardized our lives, improvised the ‘official’ abduction narrative, which corresponded to events many experienced at the time, and therefore was more convincing than the ‘real’ events.

The facts explored in this paper are extracted from a project on abandoned dwellings. The subject is rooted in autobiographical memories, as my family was expelled from their home twice, in 1982 and 1986, and had to find refuge elsewhere. It started in 2009 as a photographic series, and grew like a rhizome of storytelling, following the ‘principles of connection and heterogeneity’ and the ‘principle of multiplicity’21 fed by intersecting documents, archaeological findings and testimonies that frequently provided conflicting results, as is the case in the present story. The work also took shape in a PhD dissertation in Art History defended on June 20, 2016.22 It was questioned whether Art History was a good disciplinary fit. The PhD was undertaken under the supervision of Jean-Yves Andrieux, a specialist of architectural heritage and its identity. In the course of its progression, it integrated artistic, literary and cinematographic representations of Beirut produced during the so-called war (1975–1990) and post-war (after 1990) periods, so that ‘Art Histories’ would have been a more appropriate label. With the dissertation being almost as dispersed as its subject, one could have seriously wondered if it were ‘a disciplinary text according to academic disciplines?’ ‘No’, affirmed jury member Catherine David. In her remarks, David perceived the piece as ‘not a discourse of authority, it is porous and open to doubts and questions’, while acknowledging a proximity of approach with Jacques Rancière’s descriptions of modes of connexions and forms of intelligibility.23 In a country where historical narrative is a subject of conflict – the publication of a history schoolbook has been debated for decades – and at times when global politics evolve into seemingly unexplainable directions, art and research might provide something of a methodology for coping with contradiction, retrieving Rancière’s argument that ‘writing history and writing stories come under the same regime of truth’.24 Ultimately, what matters is neither the initial subject – or how wars and crises affected Beirut’s residential buildings – nor the will to write a history of contemporary art in Lebanon or a history of Lebanon. What matters is how abandoned dwellings and the stories they generate could be an instrument to re-appropriate cities that are confronted by various forms of violence, ethnic segregation, authoritarian surveillance and control, and neoliberal policies.

A House, Opposite the Library

One day, in the reading room of the ‘Bibliothèque Orientale’, a librarian asked what my study was about:

– Abandoned houses, I answered.

– I must show you something, she said.

As we walked to a window, she pointed towards an elegant neoclassical façade crowned with Roman style sculpted garlands and lions. She asked if I knew about it.

– Everybody knows.

Owned by the H., a Syrian family who settled in Switzerland, the graceful construction was notorious because Pierre Gemayel (1905–84) inhabited its third floor. Nicknamed ‘Sheikh Pierre’, this pharmacist was the founder of the ‘Kataeb’, a right-wing Christian party, and father of Bachir and Amine Gemayel, who were successively elected at the Presidency of the Republic.25 In 1975, a demarcation line divided the city within two belligerent sectors: ‘West Beirut’, controlled by Palestinian and leftist movements, and ‘East Beirut’, dominated by Christian parties, including the ‘Kataeb’. The H. building and the ‘Bibliothèque Orientale’ were on the eastern side, a few yards away from the front. The ‘Kataeb’ fortified the area, henceforth-designated ‘As-Sakhra’ (the rock), which was Pierre Gemayel’s nom de guerre. Despite its uncanny location, the H. building was not on a gunfire axis and persisted. As war went on, Gemayel terminated his rent agreement and moved to the clan’s estate in Bickfaya, in the heart of the ‘Christian stronghold’.

Nowadays, an external single passenger elevator, assembled for the politicians’ use, evokes his past presence. It is out of order, as the whole construction is in a state of dereliction, with the exception of one flat on the second floor, where tenants who live abroad come sporadically. One reason for which the H. building haunted the librarian was the fact that, from time to time, she suddenly saw traces of human presence, such as lights on or carpets on the balcony.

– There is a mystery.

– Indeed. But, it’s neither Gemayel nor the people who turn the lights on. It’s Victoria.

Meet Victoria

In order to explain who Victoria is, I must first introduce Valerie, and more broadly, my photographic practice. When shooting inside abandoned dwellings, I asked people to ‘inhabit’ the deteriorated spaces. This was a repeated re-enactment from a sequence of Maroun Bagdadi’s Hamasat (Whispers), a 1980 film documenting lives and thoughts of the Lebanese during the war. In the opening scenes, the camera follows poet Nadia Tueni wandering in the ruins of Beirut’s centre, lamenting on its annihilation. Tueni appears as an epitome of elegance and dignity in the middle of disaster. Tueni died three years after the film was made and the movie was not released until the 2000s. As a consequence, her fragile presence in the filmed images and her recorded voice is something of a post-mortem apparition.

Disappearance, death and living remains are among the themes Rebecca Schneider explored in ‘Performance Remains’, where she argues that performance can be engaged as what remains, rather than what disappears.26 Though it is inevitably promised to disappearance, the body can become ‘an archive and host to a collective memory’.27 Moreover, Schneider insists on the fact that ‘performance becomes itself through messy and eruptive reappearance, challenging, via the performative trace, any neat antinomy between appearance and disappearance, or presence and absence’.28 This is particularly relevant with Tueni’s appearance in Hamasat that haunted me for years. Though, when I decided to re-enact her action in abandoned houses, there was no question of reproduction or imitation. Each person behaved in accordance to her body, her sensibility, and her interaction with the space.

Another source of inspiration for these living presences came from Aby Warburg’s reading of Renaissance painting. Warburg evokes Ninfa, the auratic heroin. The ephemeral movements of her hair and draperies are seen as displaced indications of the pathos of images.29 In our case, pathos relates to catastrophes that happened and catastrophes to come. In the early 2000s, the Arab world was already the ‘part of the planet where man has the least chances for self-fulfilment. And a fortiori, woman’.30 A year or so after the beginning of the photo series, the region fell into a cataclysmic spiral that devastated countries and displaced millions of civilians. In the wake of these unfolding events, while inside spaces that were damaged during a previous conflict, and eventually served for military command, snipers, bunkers and torture, the human presence injected a dialectic between life, death and survival.

On November 28, 2010, writer and theatre director Valerie Cachard came for a photo session inside a modernist edifice designed in the 1950s by Polish architect Karol Schayer. A man was guarding the building. Neighbourhood rumours suggested he was ‘Syrian intelligence’. We told him we were gathering evidence for the international probe of the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri that took place in the vicinity. Our argument was not very credible, as Valerie was wearing a costume she fabricated for Matriochka, a performance she staged two weeks earlier about femininity and memory, but he let us in. In the aftermath, Valerie expressed a wish to write an essay about the photographs. She organized interviews aiming to establish links between my personal history and abandoned houses. Afterwards, she accompanied me on the ground. Unexpectedly, Valerie’s uncle inhabited the first building I randomly selected, before he immigrated to Brazil. She searched for belongings of his household, but found only traces of others, mainly police records. This visit paved the way to one year of informal archaeological missions. Many buildings were filled with objects, furniture, and papers. We established a protocol according to which we would retrieve official documents and personal artefacts (letters, photographs, diaries, artworks) that could provide evidence on the lives of the former inhabitants and eventual illegal occupants (squatters, warriors…). We recovered, cleaned and archived approximately 700 relics with the aim of either returning them to their heirs or transferring them to a public institution.

Gregory Buchakjian, Valerie Cachard exploring Victoria K.’s former apartment, 2011, digital photograph.

On September 7, 2011, at 8PM, we came to the H. building. On the first floor, we found a closed door pierced on the bottom by a hole. We crawled through the opening and entered a central hall apartment. It was dark and one could barely see anything except three-arched windows and filthy curtains. Valerie lit a flashlight and moved from one room to the other, illuminating the ground covered with papers, clothes and fashion accessories. She evolved very fast, as if she didn’t want to miss anything. Her displacements made the flashlight irradiate abruptly. This optical phenomenon made me anxious. Visiting abandoned spaces is already illegal and thrilling; doing it after dawn was another thing. I was standing, incapable of doing anything but begging her to leave. While she ignored my requests and kept on examining the belongings, my anguish worsened. Ultimately, I managed to convince her to leave, but not without promising a forthcoming visit.

Two weeks later, we accomplished a proper inspection. From the archive Valerie collected surfaced the character of Victoria K. Victoria was born on January 6, 1910.31 She never married, and devoted her life to the ‘Collège Protestant Français’ as a teacher and supervisor. Very meticulous, she kept her notebooks and correspondence with children’s parents, colleagues, administration, and two successive principals, Louise Wegmann and Françoise Bordreuil, who both hailed her dedication to her work. One of the most precious pieces we rescued is her certificate of the Academic Palms, granted by France’s Minister of Education on January 28, 1957. As my mother Annie was a ‘Collège Protestant’ alumna, I asked her about Victoria and showed her some pictures. Annie immediately recognized her former tutor:

– Such a straightforward and authoritarian figure!

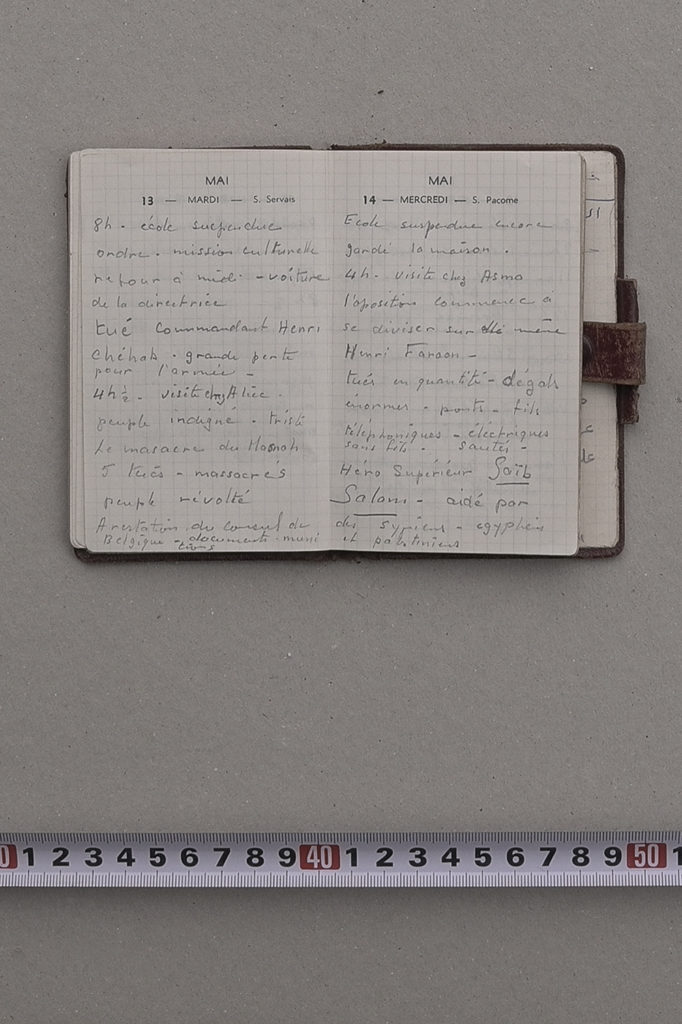

Victoria K.’s agenda for the year 1958, opened on May 13-14, rescued from Victoria K.’s former apartment.

Victoria’s wars

Victoria witnessed the crisis that shook Beirut in the spring of 1958, and was somehow premonitory of the bigger one to come. Her agenda of that year shows her thoughts and political views.

Sunday, May 11

(…) Strange sensation:

Lebanese Phalangists [‘Kataeb’] discover preparation for demonstration (coup d’état) of the Syrians-Egyptians.

Monday, May 12

8 AM – class and normal life in Beirut

8:30AM, worried parents withdraw their children.

Noon: empty classes

2:30PM. External personnel evacuated.

Tormented night. Fire.

Curfew

Tuesday, May 13

8AM – school suspended (…)

Killed, commandant Henri Chehab. Great loss for the army.

People outraged – sad

Massacre of the Masnah

5 killed – massacred

People revolted

Arrest of the Belgian consul – documents – ammunitions

Wednesday, May 14

School suspended still (…)

The opposition starts to divide itself

Numerous killed – enormous damage – bridges – telephone and electricity cable destroyed.

Superior hero: Saïb Salam, helped by the Syrians, Egyptians and Palestinians.34

In 1975, Victoria spent some time in the mountains before returning home, after the deployment of the Arab Deterrent Force, created by the Arab League, in October 1976, to supervise the truce. In 1977, her friend Marie, the widow of a prominent Lebanese painter, wrote from her retirement in Alsace:

During the past two years, not a single day passed without thinking and praying for you. As I knew who inhabits your house [Gemayel], I was sure you had nothing to fear from guns and artillery, and that food and water would be supplied to you without fault.35

Personal belongings rescued from Victoria K.’s former apartment.

Victoria’s Disputed Death

Gathered papers corroborate the life of Victoria until the 1990s. Subsequently, there is a 770 USD invoice the Elie Saab funeral service company issued on December 12, 1997, ‘for the inhumation of the late Victoria K.’, who was less than a month from her 87th birthday. The bill comprised formalin injection, clothing, coffin, hearse, and fees for undertakers (all for 650 USD), and flowers (for 120 USD). The account was settled three days later. But, there is a complication to this seemingly conclusive trail of evidence pointing to her death. Medical prescriptions and bills processed with her name, dated years later, appear to directly contest this assumed proof:

– September 13, 2001: Prescription for Caltrate 600 (1 pill/day), and Maltofer (3 pills/ day, after meals), Dr. Emile F., M.D.

– January 31, 2002: Radiology (Thorax, facial), Haddad Hospital.

– January 31, 2002: Blood test (Complete blood count, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, Urea, Creatinine, Blood sugar, electrolytes, T3, T4, Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone), Haddad Hospital.

At this point, Valerie Cachard and myself were confronted by unearthed items of hypothetically indisputable authenticity that provided contradictory knowledge. In order to find an explanation, we constructed plausible scenarios based on the established facts or suppositions.

Explanation 1: ‘There must be a writing / typing error’.

Everyone can make a mistake, except that it is incongruous to write or type 1997 in 2001 (or 2002), and vice versa.

Explanation 2: ‘There must be more than one Victoria K’.

Victoria didn’t have children, nor did her brother Antoine who passed away in 1977. Yet, Antoine’s wife was named Victorine. According to Marie O.’s above-mentioned letter, the two sisters in law were like ‘real sisters’.36 But while their names were alike, they were not identical and it is highly improbable that a mix-up would have occurred. No family would accept the name of a deceased person being replaced by a living member, and no patient would tolerate being assimilated with the dead.

Explanation 3: ‘Someone stole Victoria’s identity after her death’.

Who, why and how? An illegal immigrant? Someone who wanted to benefit from her medical insurance? How did this person manage to cheat the authorities and the insurance companies?

Theoretically, each of the hypotheses to explain the contradiction in Victoria’s death might have happened. In reality, all are very unlikely, such that the contradiction seems irresolvable. Archives and histories are riddled with contradictions caused by disputable evidence and competing interpretations. The case of Victoria’s death is in this way exemplary rather than anomolous. Foucault identified two levels of contradictions: ‘that of appearances, which is resolved in the profound unity of discourse; and that of foundations, which gives rise to discourse itself’.37 The contents of the funerary bill and the medical prescriptions are not discourses that could have been contradictory in the epistemological or theoretical sense, but are pieces of evidence whose outcomes contradict in such a way that they contest the validity of the overall research – as one or both must be false, the research lacks coherence. What if our investigation was a criminal probe? Would the court adopt Nolle prosequi? Or, would they pick up one of the three stories; elevating it into reality, and dismissing the others two as less likely hypotheses and probable fictions? These explanations appearing accurate but not plausible, the situation positioned itself as the precise reverse of parafiction, as ‘parafictioneers produce and manage plausibility’, as the opposite of accuracy.38 Instead of rooting Victoria’s story in reality, archeology was transmuting it into fiction.

Post-Mortem: Self-Proclaimed Guardians of Beirut’s Abandoned Houses (and Their Dead Dwellers)

The conclusions of our investigation were very annoying at first hand. Contradictions contested the archive as a reference of validity and the story itself wasn’t even relevant to be told as a fable, being deprived of a consistent and satisfying ending. However, in the long run, Victoria’s death is a symptom produced by the city, among innumerable others. Whatever the qualities of each of these symptoms or fragments, the validity of the whole research relies on the gathering into a rhizome of these symptoms that, as Jacques Le Goff has advocated, must arise from a multiplicity of provenances:

But just as the twentieth century has criticized the notion of historical fact… today it criticizes the notion of document. The document is not innocent, raw material…the document is what remains. At the same time, the range of documents has been broadened. Traditional history reduced it to texts and to the discoveries of an archeology too often separated from history. Today documents include spoken word, the image, and gestures.39

Most artists, writers and academics concerned by the histories of Beirut and its inhabitants were simultaneously researchers, observers and also objects of their own research, being themselves residents of the city. This kind of reciprocity is noticeable in Lamia Joreige’s Objects of War (2000), an installation comprising videos in which interviewees were asked by the artist to talk about an object that had some significance for them during the war.40

Each person chooses an object, ordinary or unusual, which serves as a starting point for his / her story. These testimonials while helping to create a collective memory, also show the impossibility of telling a single History of this war. Only fragments of this History are recounted here, held as truth by those expressing them. In Objects of War, the aim is not to reveal a truth but rather to gather and confront many diverse versions and discourses on the subject.41

In addition to the filmed interviews, Objects of War discloses the objects. The repetition between the original artifacts and the filmed testimonies describing them gives the piece, according to Jalal Toufic, the value of a war memorial, and serves to strengthen its authority.42 As Susan Little writes,

treating recorded verbatim testimony as a ‘guarantee of reality’, which may be inserted into a production to frame it with documentary authority, appears tantamount to retroactively securing value in ontology. This configures testimony as proof of experience that was once present, rather than as something that can still transmit remains.43

While most people interviewed in Objects of War are acquaintances of the artist, in Here and perhaps elsewhere, Joreige travels through Beirut, asking people in the street, one question: ‘Do you know anyone who was kidnapped here during the war?’44 Taking as a departure point the above-mentioned disappearance of her uncle (Lamia and Khalil Joreige are siblings), she tries to recover a hidden reality through encounters. During the progression of the enquiry around abandoned houses, I integrated representations of positions belonging to various social sectors: media, scholars, artists (including filmmakers, writers) and neighborhood (dwellers, passers-by, beggars, janitors, refugees, partisans). In this last category, encounters were not scheduled, but sudden and unpredictable, thus affecting their trajectories. While walking in the street or taking photographs, someone would come and suggest going in a specific direction, ‘where more spectacular ruins are visible’, or eventually order ‘not to take pictures of that buildings’. These interferences correspond to Guy Debord’s ‘possible rendezvous’: ‘the element of exploration is minimal in comparison with that of behavioral disorientation’.45 Instead of clarifying the narration, they break its linearity into a multiplicity of possible paths.46 A part of their multiplicity, these encounters, while rooted in the city’s reality, produce stories that seem unreal. This happens with Lamia Joreige, as the answers to her questions were ‘stories that were both visceral and vague, and off the point. They slip between fact and fiction, between what seems to be a straightforward recollection of past events and what is clearly an interpretation of memories performed at the present’.47 In the case of Victoria, throughout the efforts to stitch together her story, emerged three ‘possible rendezvous’ with men claiming to be guardians of deserted edifices and protectors for their (dead) (former) inhabitants.

Gregory Buchakjian, Abandoned mansion in Zokak el-Blat, Beirut, central hall with a mural depicting ‘Hajj’ Zouheir Shehadeh, 2013, digital photograph.

Guardian 1: The ‘Sheikh’ and the ‘Hajj’

Victoria used to spend summer vacations in Bickfaya (the same town as Gemayel), leasing the property of a certain Mr Kl. Mr Kl. was the grandfather of Karen Kl., another person who played a role in my project. In November 2009, a friend, Philippe, told me about the house of his grandparents that was looted and heavily damaged during the strife. Philippe wanted me to see the property before its expected demolition. The space was compelling for its lost grandeur, and unsupportable, with the scent of dirt, accumulations of shoes and the skeleton of an unidentified animal. Wondering what could be done in this wreck, I ran into Karen Kl. Karen was an illustrator who moved to Barcelona. For a period of time, she lived there without a residency permit, and squatted in informal dwellings. Her story made her the perfect candidate to be the first person to inhabit my pictures. The house was located around Zokak el-Blat, on the western edge of Beirut city centre, in the opposite side of the front line during the war. After the session with Karen, that had more to do with performance than photography, I searched for other locations in the same vicinity. My walks led me to a nineteenth century mansion crumbling under a Ficus tree. An old man, resting in an armchair, prevented me from entering. Very politely, he announced himself as the sentinel of the area, outlining his religion (Shia Muslim), his origin (South Lebanon), and his profession (pharmacist).

– I was the assistant of the ‘Sheikh’!

– Which ‘Sheikh’?

– ‘Sheikh Pierre’ [Gemayel]!

Three years later, I came back and managed to step inside. The once sumptuous central hall with a stucco ceiling had been transformed into a sanctuary devoted to ‘Hajj’ Zouheir Shehadeh, commander in the ‘Islamic Resistance’, a paramilitary group fighting the Israelis in South Lebanon. On a wall, over a fresco imitating marble, militants painted a mural depicting Shehadeh as a martyr (he was killed on February 21, 1986, while undertaking an operation), a landscape depicting a prisoner’s camp with an observation tower, a warplane (reminiscent from WWI), flames and a red sun. At the end of the day, the same man was a self-proclaimed custodian for both the (Christian) ‘Sheikh’ and the (Muslim) ‘Hajj’.

Gregory Buchakjian, Man trying to smash a door, 2013, digital photograph.

In March 2013, Valerie Cachard bumped into a man in his sixties. Claiming that he ‘grew up with “Sheikh Bashir” and was a bodyguard of “Sheikh Pierre”’, he promised to introduce us inside Gemayel’s former apartment, which had remained inaccessible. Though, instead of going towards the upper floor, which Gemayel inhabited, he intruded through a window, inside the kitchen of Victoria’s home. A locked door separated the kitchen from the rest of the habitation (which meant that someone who had the keys came and closed doors). The former bodyguard unleashed all his strength against the door, trying to destroy it by any means. The situation was incongruous: what was behind was reachable from the main entrance. Our bodyguard didn’t know where the entrance of this apartment was. He also ignored the floor Gemayel had inhabited. Or, perhaps, knowing that there was no access, he tried to fool us. In any case, his violent attempt to crush the door was unbearable for Valerie, who felt he was killing Victoria for the second (or first? Or third?) time. She begged him to stop.

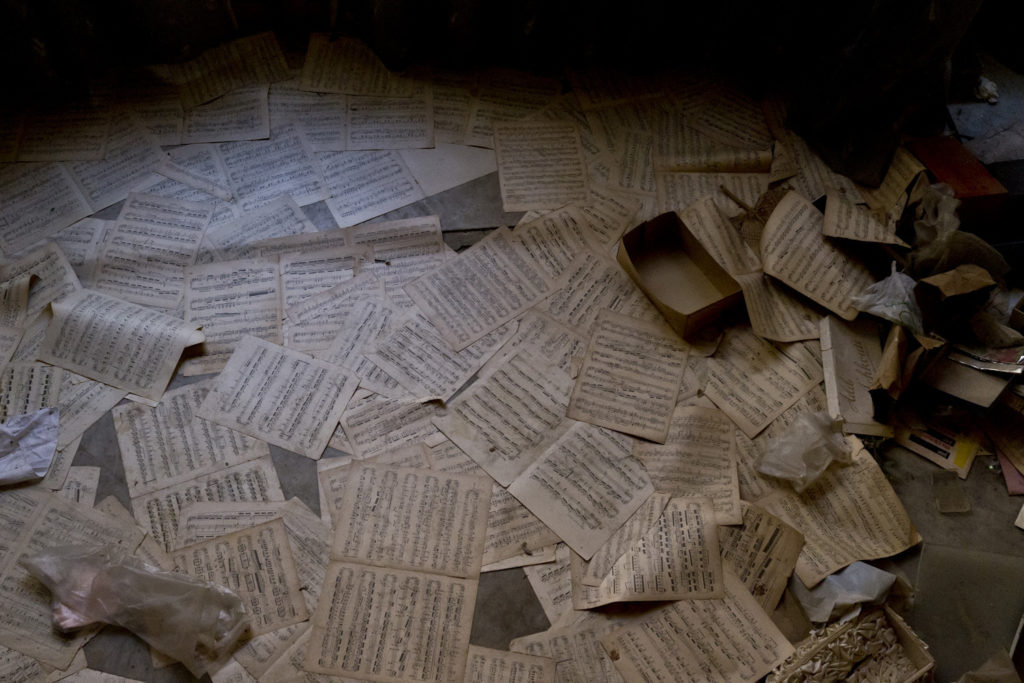

Gregory Buchakjian, Dismantled musical scores in the central hall of Victoria K.’s former apartment, 2012, digital photograph.

Guardian 3: The Sleeper

The third and last encounter with a self-proclaimed guardian took place on Sunday October 4, 2015, at noon, inside Victoria’s place. I went there with Maya Akiki, whose mother was another former pupil of Victoria. When we arrived, the door was open and the central hall empty. Previously, in 2012, an astonishing spectacle had occurred: hundreds of dismantled musical scores covered the ground. An unidentified person took the time, for unclear reasons, to unstitch pages from Victoria’s repertoire, disseminating Chopin’s Nocturnes and Beethoven’s sonatas. While this anonymous and ephemeral installation had vanished, another surprise greeted us: a young man was sleeping; lying on a mattress placed in the middle of a bedroom, with, next to him, a pair of shoes, a bottle of mineral water, and other belongings. Our presence woke him up. He said hello and explained he was here to look after the place:

– This is the residence of ‘Sheikh Pierre’!

He ignored that Gemayel had been the tenant, not the landlord of the residency. As for the bodyguard, he also ignored the fact that Gemayel didn’t inhabit this apartment. The lack of knowledge shared by the two partisans is representative of the approximate way people engage and read the city. When giving an address, most people don’t mention street names and numbers but provide a path based on informal landmarks that can be public or religious monuments, banks, supermarkets, or even ‘the old dog sleeping on the sidewalk’. In the case of Gemayel’s residence, imprecision may be due to the absence of physical indication, like doctor’s signs. Though signs can be misleading. For instance, the door adjacent to my studio in a mixed-use building bears a sign for Dr Mounzer S., endocrinologist. I have never seen Dr S. in person, sometimes his secretary. Dr S.’s door is closed most of the time, so that for nine years, his patients have been ringing to my door searching for him. When Walid Raad came to visit, he recognized the sign of Dr S.: It appears in Livre d’or, Notebook volume 57. Allegedly attributed to a certain Dr Fakhuri who, between 1976 and 1978 ‘exposed a frame of film every time he came across the sign for a doctor’s or dentist’s office’;48 Livre d’or is a component of Raad’s Atlas Group. Consequently, I couldn’t conclude if my neighbour’s clinic really existed.

Back to the young man sleeping in Victoria’s house: what was even more surprising than his spatial confusion, was his relation to time. He seemed unaware that the ‘Sheikh’, about whom he was speaking as if he would come back after five minutes, died thirty years ago, which was much before his own birth. The young man also précised he was defending the edifice from burglars, thugs, drug dealers and people coming to do ‘unclean things’. As he pursued his exposé, I shot Maya moving between the curtain and the three-arched window. He indicated that he gathered the books that were in acceptable condition and brought them to a religious charity. Then, he described how he intended to repair the whole structure whilst he didn’t know who the proprietors were. Before we left, he said we were lucky that we had managed to enter: before going to sleep, he had forgot to padlock the door. I warned him it might be dangerous to sleep in an accessible deserted site. He answered:

– Don’t worry; the house protects me!

1. Juillet, mois de la photographie au Liban (Beirut: 1998), 168.

2. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Latency,’ in Home Works. A Forum on Cultural Practices in the Region. Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria, April 2–7 2002 (Beirut: Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts Ashkal Alwan, 2003), 40–49.

3. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Tayyib Rah Farjik Shighli (Fine, I Will Will Show You My Work),’ Al Adab 49:1–2 (2001): 36.

4. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, ‘Lasting Images,’ in Home Works II. A Forum on Cultural Practices, October 31–November 6, 2003, ed. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie et al. (Beirut: Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts Ashkal Alwan, 2005), 142–43.

5. Hal Foster, ‘An Archival Impulse,’ October 110 (2004): 3–22.

6. T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2013), 182.

7. Arab Image Foundation, Mission Statement, accessed 23 June, 2017, at http://www.fai.org.lb/Template.aspx?id=1.

8. ‘Building City and Nation: Space, History, Memory and Identity,’ organized by Samir Khalaf, American University of Beirut and Order of Architects and Engineers of Lebanon, 1–3 July, 1999.

9. Walid Raad, ‘The Atlas Group Archives,’ accessed 27 February, 2017, at http://theatlasgroup.org.

10. Also known as Sidon, city in South Lebanon, from which both Madani and Zaatari are native.

11. Akram Zaatari, ‘Photographic Documents/Excavation as Art,’ in The Archive, ed. Charles Merewether (London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 181–84.

12. Ibidem.

13. Sarah Rogers, ‘Out of History: Postwar Art in Beirut,’ Art Journal 66:2 (2007): 9–20.

14. ‘Interview: Walid Ra’ad by Alan Gilbert,’ Bomb Magazine 81 (2002), accessed 28 June, 2017, http://bombmagazine.org/ article/2504/.

15. Foster, ‘Archival Impulse.’

16. Walid Raad, ‘Files Type A,’ The Atlas Group Archive, 2002, accessed 4 July, 2017, at http://www.theatlasgroup.org/data/TypeA. html.

17. Carrie Lambert-Beatty, ‘Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,’ October 129 (2009): 51–84.

18. Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972), 127.

19. Walid Sadek, ‘Collecting the Uncanny and the Labor of Missing,’ in Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 211–24.

20. Walid Raad, email to the author, April 7, 2017.

21. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 7–8.

22. Gregory Buchakjian, ‘Abandoned Dwellings in Beirut: Wars and Transformations of the Urban Space, 1860–2015’ (Paris: Université Paris-Sorbonne, 2016).

23. Catherine David, comments during the PhD defense of Gregory Buchakjian, Université Paris IV Sorbonne, 16 June 2016.

24. Jacques Rancière, Le partage du sensible: esthétique et politique (Paris: La Fabrique, 2000), 61.

25. Bachir Gemayel was elected on 23 August 1982, during the siege of Beirut by the Israeli army. He was assassinated on 14 September 1982, and was succeeded by his brother Amine, who remained in office till the end of his mandate, 22 September 1988.

26. Rebecca Schneider, ‘Performance Remains,’ Performance Research 6:2 (2001): 100–08.

27. Ibidem.

28. Ibidem.

29. Georges Didi-Huberman, ‘Aby Warburg et l’archive des intensités,’ in ‘La ressemblance du visible/Mémoire de l’art,’ special issue, Études Photographiques 10 (2001): 144–68.

30. Samir Kassir, Considérations sur le malheur arabe (Arles: Actes Sud, 2004), 9.

31. ‘Collège Protestant Français de Jeunes Filles’, Inspection Bulletin, May 19, 1965. Document collected by Valerie Cachard from Victoria K.’s former apartment.

32. I also studied at the ‘Collège Protestant’, after Victoria’s retirement, but during the mandate of Mrs Bordreuil. I immediately recognized her signature that used to be on each of our monthly grade bulletins.

33. The 1958 Lebanon crisis was a social, confessional and political conflict and a proxy war opposing Muslim and Leftist rebellion supported by the United Arab Republic and pro-western government of President Camille Chamoun. This latter requested a U.S. military intervention to topple the opposition.

34. Victoria K., ‘Agenda 1958,’ 1958. Document collected by Valerie Cachard from Victoria K.’s former apartment. Translated from French by the author.

35. Marie O., ‘Letter to Victoria K.,’ November 15, 1977. Document collected by Valerie Cachard from Victoria K.’s former apartment. Translated from French by the author.

36. Ibidem.

37. Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge, 151.

38. Lambert-Beatty, ‘Make-Believe,’ 72.

39. Jacques Le Goff, History and Memory, trans. Steven Rendall and Elizabeth Claman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), xvii.

40. Lamia Joreige, Objects of War No.1, 2000, Tate, accessed 31 March, 2017, at http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/joreige-objectsof- war-no-1-t13247.

41. Lamia Joreige, ‘Objects of War’, accessed 30 June, 2017, at http://www.lamiajoreige.com/installationsDetails.php?OB JECTS-OF-WAR-9.

42. Ghada Sayegh, ‘Images d’après: L’espace-Temps de la Guerre dans le Cinéma au Liban, du «Nouveau Cinéma Libanais» (1975) aux Pratiques Artistiques Contemporaines (de 1990 à nos jours)’ (PhD Dissertation, Paris Ouest Nanterre la Défense, 2013), 238–41.

43. Susan Little, ‘Repeating Repetition,’ Performance Research 20:5 (2015): 44–50.

44. Lamia Joreige, ‘Here and Perhaps Elsewhere,’ accessed 2 July, 2017, at http://www.lamiajoreige.com/filmsDetails.php?HOU NA-WA-ROUBBAMA-HOUNAK-13

45. Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the Dérive,’ Les Lèvres Nues 9 (1956), trans. Ken Knabb, accessed 9 March, 2017, at http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/theory.html.

46. Ibidem.

47. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, ‘Contemporary Art Practices in Post-War Lebanon: An Introduction,’ in Out of Beirut (Oxford: JRP|Ringier/Modern Art Oxford, 2007), 81–89.

48. Raad, ‘Files Type A.’