A Geography Without an Author: Unreliable Facts, Fantastical Fictions

Fiona Curran

To cite this contribution:

Curran, Fiona. ‘A Geography Without an Author: Unreliable Facts, Fantastical Fictions.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/geography-without-author-unreliable-facts-fantastical-fictions/.

Everyone trusts the narrator but the narrator can be wrong.1

– Pierre Huyghe

Pierre Huyghe’s 2002 exhibition L’Expédition scintillante: A Musical at the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria presented a scenario for a future expedition. Each floor of the museum space staged a moment of an imaginary journey with each level corresponding to one act of a musical tale. The exhibition blended fact with fiction incorporating real-time events with static objects and documentation taken from a range of historical references. This paper takes Huyghe’s exhibition as a starting point to reflect on a broader network of correspondences between this work, Edgar Allan Poe’s 1838 novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and the work of the French philosopher Michel Serres. It is Serres’s ‘general theory of relations’ and ‘philosophy of prepositions’2 that acts as an errant guide to the connections being drawn between these different historical works. It is also Serres’s questioning of science as the traditional and dominant discourse of reason that informs my response to the theme of validity. Serres’s philosophy is dense with metaphor, which is liberally used in order to disrupt disciplinary boundaries and conventional epistemological frameworks. As readers, we are called upon to follow his prepositional mode, and to keep moving within and between different configurations of knowledge, forming new connections as we travel. These approaches to dispersed, relational, aleatory, and speculative forms of knowledge production can be seen to circle and contest notions of validity as a means to ground or substantiate knowledge. This approach to the formation and reformation of thought follows a topological method that is spatial in extent – a device that Huyghe also deploys in his practice.

This paper will involve lengthy descriptive passages that seek to restage/recall the visual and textual events/objects under discussion at the same time as calling further references into the frame. Faithful description, reproducibility, and replicability are empirical conventions linked to traditional methods of validation in the natural and social sciences. However, when description leads away from ‘authentic’ and exhaustive transcription towards speculation, association, and allusion – methods more frequently present in literary and artistic forms of practice – these validatory tools are exposed as necessarily partial and fragmentary, always subject to excess.3 Huyghe frequently sets up ‘laboratories’ for human and non-human actors to play out scenarios that resist resolution. He can be seen to tarry with aesthetic forms of validation through, for example, his use of the hypothesis, documentation, and testimony, but to simultaneously undermine any notion of truth or authenticity that these aesthetic forms might seek to establish or reinforce. The emphasis on open-ended relations can act as a provocation to engage with material in new ways at different historical moments and to challenge accepted forms of interpretation. Rather than seeking the closure of representation and the foreclosure of knowledge, adopting more speculative and open-ended approaches to the formation and the reformation of knowledge might resist notions of validity as established by specific disciplinary conventions and frameworks of practice. Equally however, the emphasis on open-ended relations can leave us, as readers and viewers, having to do extensive work in order to resituate histories and to activate them for the present. From this perspective, Huyghe’s seemingly disruptive tactics might signify ‘a reluctance to synthesize and organize’ information resulting in a position that ‘forsakes interpretation’.4

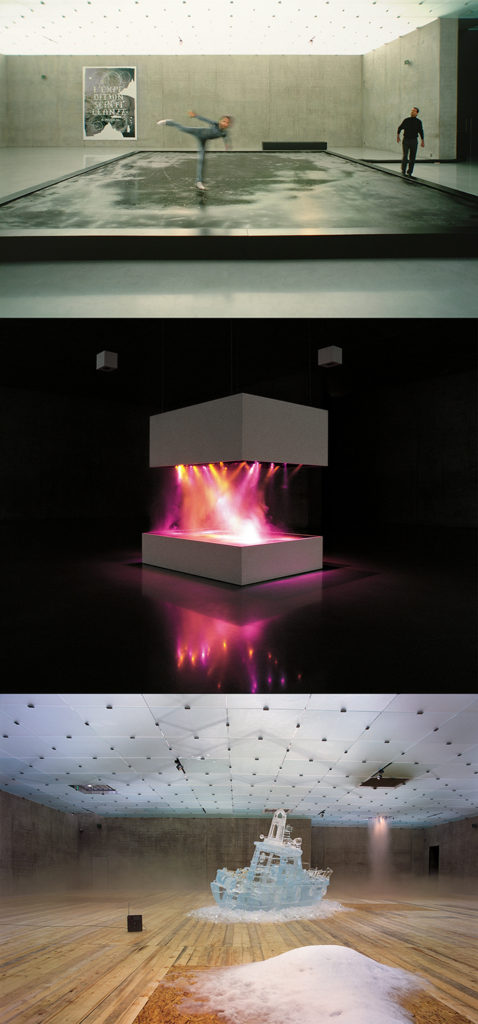

Pierre Huyghe, L’Expédition scintillante: A musical, 2002, mixed media, installation view at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria, image courtesy of Markus Tretter, Pierre Huyghe and Kunsthaus Bregenz.

Act 1 on the first floor of L’Expédition scintillante: A Musical presented the viewer with a life-sized boat intricately carved from ice that would gradually melt throughout the duration of the show. This boat presented both the means of travel as well as a material embodiment of the destination for the proposed expedition, the frozen continent of Antarctica. A radio emitted sounds from John Cage’s Radio Music score, as well as broadcasts from the two offshore pirate radio stations from the 1960s, Radio Caroline and Radio Veronique, stations that circumvented broadcasting licencing laws by situating themselves in international waters beyond any individual state jurisdiction. This indeterminate political geography mirrors that of Antarctica itself, which is currently held under the terms of the Antarctic Treaty System (1959). The treaty legally suspended any territorial claims to the land by any individual nation state in favour of a collective custodial approach by a number of states, many of which were, and continue to be, in dispute with one another over the validity of prior claims to the territory.

The last continent on Earth to be formally charted and framed into organised systems of knowledge, the Antarctic stood for thousands of years as an imaginary place on the maps of ancient civilisations, the mythical terra australis incognita or unknown southern land. Climate conditions prevented its full mapping by satellite images until as recently as 1997, indicating the uniqueness of the continent’s extreme meteorological conditions and its resistance to formal capture in codified systems of knowledge and visual representation.5 Ancient astronomers believed in the existence of a great southern land as a necessary counter-balance to the northern continents. The great terra incognita of the planet held out its mysteries until the late eighteenth century circumnavigations of the globe. However, even the circumpolar expeditions at the end of this ‘great’ age of exploration could not provide any certainty of the existence of the southern landmass, which remained elusive as conflicting reports of sightings of land emerged, and facts were difficult to verify. Voyagers to the Antarctic were challenged by extreme weather conditions and the presence of sea ice that could prevent further travel entirely. Natural forces disrupted attempts to impose systems of verification based on empirical measurement.

A final element of the opening act of L’Expédition scintillante: A Musical was a dramatic series of changing weather conditions that emerged from controlled vents in the ceiling. Real snow, rain and fog appeared sequentially in the gallery space. These meteorological effects were derived from Edgar Allan Poe’s 1838 book The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, which provides a series of further clues to the exhibition’s content and to Huyghe’s overall method. Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym presents an account of a fantastical journey to the Antarctic continent. The novel is famous for its experimental structure in which the author/character ‘Pym’ introduces the story in the first person claiming, in a letter written as a preface, that it is a factual account of events that took place and that he has persuaded the author, Mr. Poe, to write up the truth ‘under the garb of fiction’.6 After an abrupt ending to the narrative that leaves the story unfinished (and therefore open to future interpretation and speculation by other writers, such as Jules Verne in his 1897 Le sphinx des glaces) the book then closes with a note by Poe where he recounts the sudden and distressing death of Pym following his miraculous return to America. From the outset, the narrative is beset by uncertainty over authorship and over its veracity. The story follows the twists and turns of a journey south by Arthur Gordon Pym, beginning with his stowing away on a whaling ship belonging to his best friend’s father, and moving through a mutiny and violent killing of members of the ship’s crew, extreme weather conditions, his best friend’s death, cannibalism, rescue, encounters with lands and peoples depicted as ‘strange’, more violent deaths and the witnessing of a transcendental white figure. The original subtitle of the novel helps to frame its many acts:

Comprising the Details of Mutiny and Atrocious Butchery on Board the American Brig Grampus, on Her Way to the South Seas, in the Month of June, 1827. With an Account of the Recapture of the Vessel by the Survivers; Their Shipwreck and Subsequent Horrible Sufferings from Famine; Their Deliverance by Means of the British Schooner Jane Guy; the Brief Cruise of this Latter Vessel in the Atlantic Ocean; Her Capture, and the Massacre of Her Crew Among a Group of Islands in the Eighty-Fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude; Together with the Incredible Adventures and Discoveries Still Farther South to Which that Distressing Calamity Gave Rise.

The book was written in the mid nineteenth century, when the Antarctic continent was still officially undiscovered but on the cusp of The United States Exploring Expedition to the region to be led by Captain Charles Wilkes, who would controversially claim to have sighted Antarctic land. Wilkes was later accused of ‘immoral mapping’ and of fabricating his records based on the ‘assumption of land’ rather than any actual sighting.7 Poe’s tale is therefore a curious blend of fact and fiction drawing from historic myths and speculation that circulated about the White Continent, and included popular theories of a hollow earth proposed by authors such as John Cleves Symmes and explorers such as Jeremiah Reynolds. The novel was also influenced by factual accounts of arctic expeditions, including William Scoresby’s 1822 Journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale-Fishery; Including Researches and Discoveries on the Eastern Coast of Greenland. Scoresby’s report documented in elaborate detail the weather conditions at the Pole and the disorientating impact of the polar environment on the senses.

Writing against this backdrop of exploration and discovery, the interesting thing about Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym is that instead of journeying to unknown lands in order to acquire knowledge and bring it back to the centre, Pym finds himself spiralling into an ever-greater web of uncertainty and unknowability. Thus, the tale consistently calls into question our ability to read reality empirically through the senses or through language, both of which are challenged to the point they break down as reliable sources of knowledge acquisition. The novel can be seen to explore and contest the perceived differences between fact and fiction, illusion and truth, reason and imagination, appearance and reality, blurring the distinctions between these binaries and exposing the provisional nature of language as a tool of communication. J. Gerald Kennedy notes that what distinguishes Pym from the traditional adventure novel

Is the author’s subordination of sensational events to an implicit analysis of the process by which human beings construct rational interpretations to protect themselves from unsettling ambiguities. Arthur Gordon Pym himself performs interpretative acts throughout the narrative, making inferences and drawing conclusions which his experiences repeatedly overturn. His inability to decipher problematic texts…parallels his failure to comprehend physical phenomena on which his fate seems to depend.8

With the later ‘heroic’ age of exploration in the nineteenth century, when humans finally set foot on Antarctic land and became physically acquainted with it rather than viewing it from the ocean, the mysteries of the continent were still in place and its myths, far from dissipating, only began to grow and expand in the imagination of those who encountered its vastness and impenetrability. As environmental historian Stephen J. Pyne notes,

The problem was not solely the formidable physical geography of the ice terranes: the Ice also challenged the philosophical precepts, artistic genres, and scientific systems by which the era had understood the metaphysics (and metahistory) of nature. The abundance of the observed world was stripped away…The Promethean desire to embrace everything lost its meaning in a landscape of nothingness. In place of increasing information, there was less. In place of abundant objects, there was only ice; and in place of tangible landmarks, such as mountains and lakes, there were only abstract concepts, such as the poles of rotation, magnetism, or inaccessibility, all invisible to the senses.9

Huyghe took up the themes from Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym in the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Bregenz as both framing device and source material. Apart from the symbolic presence of the melting boat, the weather conditions in Act 1 were taken from a careful transcription of Poe’s descriptions of weather events in the tale. These meteorological episodes were translated into data, which then controlled the actual weather conditions in the gallery. In French, le temps refers to both weather and time, and the opening act of the exhibition seems to play with these entangled meanings. A small textual chart of the weather patterns was also included in the gallery space. Fiction became phenomenon and fact in a reverse order of transcription. Huyghe notes: ‘I took the weather report and I set it in motion as you would a musical score. From the ceiling of the museum, I created an authentic climate: real falling rain, snow, and fog. But all the while it’s fictional weather. A romantic time capsule’.10 Beyond the poetics however, these comments are unsettling. Huyghe’s gestures of appropriation and (re)creation hint at forms of mastery and control that frequently manifest in his practice as the delimiting of spaces for carefully orchestrated actions or events to ‘play’ out. Specific sets of actors (human and non-human) inhabit a set of conditions akin to a living laboratory whilst he appears to step back in order to observe and record what unfolds. We might question the validity of this approach in a practice that gives the appearance of critiquing traditional epistemological frameworks yet, at times, seems to uncritically replicate traditions of knowledge production that subscribe to a belief in an external point of objectivity. As numerous philosophers of science and feminist, queer and critical race theorists have shown, however, such positions occlude the presence or situated particularities of the observer under the cloak of a perceived sense of impartiality.11 In the context of a work referencing historical exploration, Huyghe’s positioning might be additionally troublesome in this respect as, particularly when read in relation to his later voyage to Antarctica in the work A Journey That Wasn’t (2006), it replicates colonial exploratory practices of ‘discovery’ and observation.12

In Act II, on the second floor of L’Expédition scintillante: A Musical, the visitor encountered a music box in a darkened room playing out ‘a concert for penguins’. Two boxes mirrored one another above and below with coloured lights inside that shifted in response to the sounds of Erik Satie’s 1888 composition Gymnopédies. A thick fog of dry ice permeated the space and, at the end of each musical sequence, the lights in the gallery were brought up to bathe the space in a warm pink glow mimicking a sunrise or sunset. The music machine also referenced a ‘psychedelic experience’ suggesting a further space to confound the senses and disrupt perceptual frameworks and linear flows of time via drugs, colour, music, and excessive sensory stimulation. In Act III, the final stage of the journey in the museum, the visitor arrived in a room with a large black ice rink and a solitary ice skater looping in rhythmic circles around the ice. Several books were distributed around the gallery space on this level with an image of penguins on their covers. The books contained further images and text arranged to reflect the journey just undertaken through the museum space and future journeys to come. The book’s preface began with the following text, set against an image of Giotto’s fresco of St Francis’ Sermon to the Birds (1297–99): ‘The invention of a no-knowledge zone. The real means to discover it. The call of birds to Saint Francis. The Poetic Expedition’.13 This dense overload of visual and textual references came with no interpretive panel or guide. The poetic text in the bound volumes served only to further obscure the references on display through the introduction of new ones. Claire Bishop has critiqued what she refers to as the ‘transhistorical’ use of objects and information within contemporary art practices, arguing that the ‘oneiric mélange of data…keep[s] things opaque’ and ‘labors to keep meaning withheld from the viewer’. For Bishop, this approach fails to ‘mobilize history as a powerful cultural weapon from which we might draw inspiration for present-day battles’ and instead reduces the poetics of the past to ‘information as ornament’.14 These concerns question the validity of Huyghe’s methods to instigate open-ended spaces of emergence as, once again, he continues to place himself in a position of mastery over the information selected and presented without offering us any explicit critique, historical interpretation or associative connection between the multiple references on display.

Huyghe’s later, related work, A Journey That Wasn’t (2006), presents an artwork that evolved over a considerable temporal duration, across multiple platforms of presentation. The project combined a journey to Antarctica that was undertaken by Huyghe, a small crew and a group of six invited artists on board a specialist research vessel. The journey was filmed by the cinematographer Maryse Alberti, one of the artists on board, and the footage was later combined with that of a second film shot in Central Park, New York, where Huyghe subsequently staged a recreation/translation of the journey as a spectacular musical event for a live audience. The combined footage from these two events was then released as a video installation for gallery display. A written text ascribed to ‘The Association of Freed Time’ that documented the journey was also published in Artforum International in 2005, between the Antarctic trip and the event in Central Park. In this essay, the narrative begins in a style that seems to mimic Poe’s authorial tricks calling into question the true nature of the account. At the same time, the opening of this text reflects on the mechanisms and the formal procedures by which information is communicated as a means to dispel doubt. In problematising the foundations on which ‘validity’ rests as a concept – is the story believable? Is the argument convincing, well grounded? Can the conclusion be logically deduced from the premise? – Huyghe’s doubling of Poe’s narrative style could be seen to reveal the fragile bases of any truth claim:

The extraordinary events and unlikely phenomena to which sailors bear witness are not easy to record. The narrative must be precise, or it runs the risk of being taken for a fabrication. For the maritime storyteller this would be unthinkable, as he and his story are inseparable. The truth, therefore, must be made believable. One way is to understate the story by weeding out exceptional details, however factual. Another option is to dress the truth in the costume of fiction by using those same details to elaborate the story.15

The frontispieces from Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and Verne’s Le sphinx des glaces also appear as images in the books of Act III of L’Expédition scintillante, as well as photographs of the Radio Caroline boat; Caspar David Friedrich’s 1824 painting The Sea of Ice; film stills from Steven Spielberg’s 1978 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind; a text in the style of a script for the three acts of the exhibition; and a glossary outlining the geographical features and principles of place naming.16 L’Expédition scintillante exists as an exhibition in the present but also as a script for a future scenario, a future journey, a future work. Huyghe presents these disparate historical and geographical reference points leaving us to draw multiple inferences from their (sometimes unfathomable) juxtapositions. Any appeal to taxonomic certainty or rational ordering that might function to structure cultural formations is disrupted by the presence of imaginative, romantic, libidinal, and ‘irrational’ counter forces. There is, perhaps, an implicit refusal to accept the order of things in Huyghe’s work being valuable as a method of practice seeking to explore the spaces and movements between objects, subjects, and epistemologies that are usually kept distinct from one another. His uses of the poetic and of spectacle, and his mobilisation of the affective encounter, whilst opening his work to some of the questions concerning mastery raised earlier, equally offer us multiple sensible experiences that bring the human into contact with non-human forces and, therefore, displace the human at the centre of things. Huyghe himself has described the exhibition as ‘a living entity’, referring to the show as ‘a kind of organism. L’Expédition scintillante can be translated as “The Blinking Expedition”…One situation can be transformed into another without losing something in the translation. It can be different but also equivalent. Something may appear then reappear somewhere else. So it is a blinking organism’.17

This exhibition-event, therefore, embodies a form of restlessness in its construction, in the range of human, material and immaterial forces that play their part across its staging. Everything is in a state of flux and is undergoing change or movement from one state to another: ice melts, weather conditions come and go, music plays as coloured lights seem to dance in response. Even when the music ends, the gallery is bathed in a moment of simulated sunshine before the show returns; the ice-skater moves rhythmically around the ice rink in and out of time to more music. In the later work, A Journey that Wasn’t (if we are to believe the ‘traveller’s tale’ as recounted via the journal entry in Artforum and film footage of the trip), the passengers and crew also encountered events beyond their control. Extreme storm conditions on board the boat affected their radio communication and navigation systems sending them off course into unknown waters and disrupting their planned destination and journey times. These experiences of the weather and time are described in terms of perceptual and sensory disruptions that echo Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and the spectacular, sometimes hallucinatory scenes encountered on Pym’s voyage, where the presence of Antarctic light and atmosphere play tricks with his ability to read reality through the senses. Empirical methods of verification and validation are questioned, different forms of meaning and systems of epistemological certainty are sought. In this uncertain space ‘no-knowledge zones’ emerge:

[R]eality is not what it used to be; it has become relative. As always, it has to be invented. As geography toyed with their senses, chemical elements and natural phenomena would conduct their movements. Perhaps they would need to invent a chemical language or ingest a drug that would alter the real rather than its perception. The journey would encounter islands and then make them disappear, producing no-knowledge zones that would emerge whenever the capacity for language to seize reality would end. The elsewhere remains a story, and the rest is exoticism. If language fails to recount the experience, an equivalence, topologically identical to the occurrence, has to be invented.18

Herein lies the heart of Huyghe’s practice – an exploration of the politics of knowledge production and a desire to translate the experience that transcends language and resists representation into a topologically equivalent event. Such events, as suggested, might be seen to function as examples of the excessive, libidinal, sensory and ‘transcendent’ realm beyond the contained and ordered domains of the rational, the logical. Perhaps the point of suggesting translation as a method is precisely because something is always going to be ‘lost’ in the process. Rather than seeking to continually ground knowledge through orthodox validatory practices such as those of reproduction and replication, translation adds a further layer of complexity to the movements of thought.

In repeated interviews with the artist and texts written about him, this reference to topology as a method of practice has surfaced as a profoundly significant element of his overall project. Topology is a method of mathematical geometry that is not concerned with exact dimensions or measurement of Euclidean qualities such as angles, lines, perspective and surfaces, but with spatial relations. A connection can be traced here to the work of philosopher Michel Serres, where topology is used as a method of practice to generate new thought. Serres initially trained in Mathematics, and his interest in topology as a philosophical method dates from this period. As a philosopher of science, he is committed to questioning its status as the dominant discourse of reason, preferring to assemble a range of disparate, and often competing discourses that defy ideas of progress in terms of any linear notion of time. For Serres, ‘time doesn’t flow, it percolates’,19 and he takes great delight in presenting a series of visual and material metaphors that help his reader to understand this notion, from references to rivers, pleats, folded handkerchiefs, and a baker kneading bread.20 Time is seen to fold in on itself, points that initially seem distant in time and space are crumpled together (as when two points are drawn at a distance on a handkerchief and it is scrunched into a ball resulting in the points occupying the same physical space). As with Huyghe’s practice, in mapping disparate discourses together within the same space of the text, Serres seeks to reveal equivalent structures in them that allow the unexpected to emerge and a transformation in knowledge to take place. At root in these speculations, therefore, is an attempt to theorise new forms of spatiality that allow new forms of thinking to take shape. Serres’s interest is to avoid any notion of fixed identities – of disciplines or ideas, of any totalising discourse or method of validation – and to attend to the possible, to the mutable relations between disparate fields of knowledge across the sciences, arts and humanities. Paul Harris comments on this approach and on Serres’s use of fiction in his work:

In the greater ecology of Serres’s work, literary texts do indeed function as ‘formal turbulences’ or ‘energy pathways’. They are embedded in a transdisciplinary setting where they serve as what Serres calls ‘operators’, nodes that establish links across scales and levels of life and between domains of experience and knowledge.21

It is in this shaping of thought via a non-Euclidean mapping or folding of space and time that it is possible to trace a connection with Huyghe’s work and his use of topology as method. For Huyghe, as well as the spatial relations afforded through thinking topologically, there is also the possibility for new forms of temporality or multiple temporalities to emerge. The question of time for Huyghe is also tied to systems of thought and the conditions under which knowledge is able to emerge and to grow. The use of an explicitly organic and ecological metaphor here is clear. The appeal to ‘natural’ forces opens thought towards the non-human and therefore questions any model of validation as intrinsically anthropocentric. This has become increasingly evident in the artist’s more recent work, such as Untilled (2012), the garden ecosystem he produced for documenta 13, and In.Border.Deep (2014), a multi-layered and multi-object work that includes living aquariums, a film depicting insects frozen in amber, and a further, deeply unsettling film that presents a monkey wearing a human face mask who has been trained to work as a waitress in a Japanese café. These works, and the most recent project After ALife Ahead (2017), which presented a bio-technical system at Skulptur Projekte Münster, build on the earlier projects under discussion from Huyghe’s practice in attempting to establish sites of correspondence across human and non-human timeframes and across multiple platforms and spaces of (re)presentation.

L’Expédition scintillante: A Musical existed as a script or scenario for a possible future journey, which then became an actual event with a voyage to Antarctica in search of an unknown island and a mysterious white penguin. These events recalled prior historical expeditions to the unknown southern land and the history of the continent as a shifting and contested physical and political geographical space. The entanglements of both works with Poe’s extraordinary tale and further literary, musical, film, and visual art references situate Huyghe’s works in an extended network of narrative relations that offer a ‘vibrating temporality’.22 A question however, still hovers over whether the journey to Antarctica ever actually took place. The title of the piece, A Journey that Wasn’t, already introduces a moment of doubt in relation to the event. Huyghe himself has, over time, been deliberately evasive when questioned about the trip, and has often provocatively played into his questioner’s uncertainties: ‘We don’t even know if I even went there – if I saw this island or the albino penguin. Maybe I did. Maybe it’s a special effect. I don’t care’.23 Fact and fiction, inside and outside, subject and object, figure and ground, here and elsewhere, Huyghe’s work, according to Amelia Barikin,

strives to keep structures open to potential: to maintain ambiguity by manufacturing moments of elegant irresolution. The individual’s ability to get a handle on the present – to experience duration, to resist the codification of time as product – has been a continued and ongoing concern of his practice.24

At other times, however, Huyghe suggests in relation to the expedition that the event did take place, although he downplays the significance of the destination itself, preferring to focus on the social aspects of the collective experience of the journey. In an interview with Mark Godfrey at Tate Modern in 2006, Huyghe talks about building up a fiction in order to ‘to give yourself the means to verify it’, thus opening up a disrupted field of truth and fiction and the role of verification.25 He repeatedly notes that he is not interested in documentary, in any process that faithfully captures the event or the experience but rather prefers to work with notions of re-scripting, re-defining, inventing and re-inventing reality. Within this framework the production of the artwork as both event and encounter offers an alternative chronological platform and a non-linear mode of history that folds, pleats, percolates, and vibrates.

Huyghe’s works present a constantly shifting set of coordinates without resolution. He uses fiction as a device for speculation and a departure point for the imagination stating: ‘What interested me was how a fiction, how a story, could in fact produce a certain kind of reality. An additif of reality’.26 His interest in the idea of the script or scenario is not about the finished object or the validation of an idea but the space of the hypothetical and the movement towards it. The journey proverbially becomes more significant than the destination and, as with the shifting geography of Antarctica, the map can never be a faithful reproduction of the territory. Serres and Huyghe ‘trace out the unpredictable, even vagrant itineraries through landscapes not given in advance’.27 The use of the ‘scenario’ might offer a counterpoint to the traditional ‘hypothesis’ of academic research in the natural and the social sciences, a form of practicing knowledge rather than seeking to reveal, disclose, or acquire it. In this form, practice is not to be confused with any linear sense of improvement or ‘making perfect’. Rather, this is a practice without a teleology and one that resists any impulse to be validated. Huyghe explores the time of potentiality, within which we can continue to speculate rather than seek to validate. This opens a space for practice based research that seeks to challenge dominant epistemological frameworks in order to allow no-knowledge zones to emerge. The topological mode, with its unfaithful approach to replicability, resists the fulfilment and validation of the possible and instead seeks a displacement and contestation of ‘fact’:

There are facts and constructions that have been part of history for a long time, which have become linked through language and a dominant sense of the imaginary. These facts are shaped by language. It’s important that the present remains speculative. That’s the idea of zones of non-knowledge, understood as something that cannot be exhausted by discourse – that can remain a reality, not in the sense of something occult, but in the sense of something that opens up the realm of possibility, even if chaotically. I’m interested in un-telling…I pursue a kind of incongruence and, as a result, tend more toward vitality, toward what grows.28

1. Cheryl Kaplan, ‘The legend of Two Islands: A Conversation Between Pierre Huyghe and Cheryl Kaplan,’ Db Artmag (2005), accessed 6 October, 2017, at http://db-artmag.de/archiv/2005/e/7/1/385.html.

2. Michel Serres and Bruno Latour, Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time [1990], trans. Roxanne Lapidus (Michigan: Michigan University Press, 1995), 127.

3. For a further discussion on the role of excess in representational practice and the use of ekphrasis in art history see Volume 0 of OAR on the theme of Response.

4. Claire Bishop, ‘History Depletes Itself,’ Artforum International 54:1 (2015): 324–29.

5. Kathryn Yusoff, ‘Visualizing Antarctica as a Place in Time,’ Space & Culture 8:4 (2005): 381–98.

6. Edgar Allan Poe, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket [1838], ed. Harold Beaver (London: Penguin Books, 1975).

7. Kathryn Yusoff, Arresting Vision: A Geographical Theory of Antarctic Light (PhD diss., Royal Holloway, University of London, 2005), 10–11.

8. J. Gerald Kennedy, ‘Introduction,’ in Edgar Allan Poe, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket and Related Tales (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), xi.

9. Stephen J. Pyne, The Ice (London: Weidenfield & Nicolson, 2003), 84.

10. Doug Aitken, ‘Pierre Huyghe by Doug Aitken (Artists in Conversation Series),’ Bomb Magazine 89 (2004), accessed 6 October, 2017, at http://bombmagazine.org/article/2669/pierre-huyghe.

11. In the context of this discussion see, for example: Bruno Latour, Science in Action [1987] (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988); and, Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ Feminist Studies 14:3 (1988): 575–99.

12. In relation to the site of Antarctica and colonial practices see: Klaus. J. Dodds, ‘Post-Colonial Antarctica: An Emerging Engagement,’ Polar Record 42:1 (2006): 59–70. For a further discussion of Huyghe’s work in relation to these themes see Fiona Curran, ‘Losing Ground in a No Knowledge Zone: Pierre Huyghe’s Antarctic Journey that Wasn’t,’ in ‘(Post)Nature / Natur(T)Räume,’ special issue, Kritische Berichte 2 (2017): 28–35. Huyghe’s choice of Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket should also be highlighted in the context of this discussion as the novel continues to be the subject of controversy due to the racial narratives contained in the text. Poe has been accused of both promoting and critiquing white supremacy and proslavery through his use of black/white symbolism and the racial stereotyping of the black characters within the novel. For more discussion of these themes see, for example: Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992).

13. The reference to Saint Francis also recurs in Huyghe’s later work, A Journey that Wasn’t (2006), where the artist staged a real expedition to Antarctica in search of an albino penguin. A Journey that Wasn’t helps us retrospectively to decipher the meaning of the earlier work as a ‘concert for penguins’. Reference is made to the strange device set up on an Antarctic island in order to communicate with the albino penguin, the device is described as something ‘not unlike a luminous, musical variation of Morse code or the vocal and visual displays animals use to communicate about their territories. Pierre called it Saint Francis of Assisi’. See: ‘El Diario del Fin del Mundo,’ Artforum International 43:10 (2005): 300.

14. Bishop’s discussion centres on Danh Vo’s installations ‘Mothertongue’ and ‘Slip of the Tongue’ at the fifty-sixth Venice Biennale. Her critique, whilst not addressing Huyghe directly, does broaden out to other artists using historical visual and textual references in their work, and see: Bishop, ‘History Depletes Itself,’ 324–29.

15. ‘El Diario del Fin del Mundo,’ 297.

16. This was a feature that would also return in A Journey that Wasn’t when Huyghe documented the coordinates of an unknown island discovered in the Pitt Islands Peninsula and named it Isla Iciosidad (Island of Idleness).

17. Huyghe in Aitken, ‘Pierre Huyghe.’

18. ‘El Diario del Fin del Mundo,’ 299.

19. Serres and Latour, Conversations, 44.

20. Idem, 58–60, 65.

21. Paul A. Harris, ‘The Itinerant Theorist: Nature and Knowledge / Ecology and Topology in Michel Serres,’ Substance 83 26:2 (1997): 46.

22. Pierre Huyghe in George Baker, ‘An Interview with Pierre Huyghe,’ October 110 (2004): 88.

23. Art21, ‘A Journey that Wasn’t’ (2005), accessed 6 October, 2017, at http://www.pbs.org/art21/images/pierre-huyghe/a- journeythat- wasn’t-2005-0.

24. Amelia Barikin, Parallel Presents: The Art of Pierre Huyghe (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 1.

25. Pierre Huyghe, ‘Artist’s Talk: A Discussion with Mark Godfrey,’ (5 July, 2006), accessed 6 October, 2017, at http://www.tate.org. uk/context-comment/video/pierre-huyghe-artists-talk

26. Huyghe in Baker, ‘An Interview with Pierre Huyghe,’ 84.

27. Steven Connor, ‘Topologies: Michel Serres and the Shapes of Thought,’ Anglistik 15 (2004): 105–07.

28. Pierre Huyghe in Marie-France Rafael, Pierre Huyghe: On Site (Köln: Walter König, 2013), 44–45.