Counter-factual Provocations in the Ethnographic Archive

Alyssa Grossman

To cite this contribution:

Grossman, Alyssa. ‘Counter-factual Provocations in the Ethnographic Archive.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/counter-factual-provocations-ethnographic-archive/.

Introduction

As recent decades have seen museums increasingly becoming the focus of scholarly attention, curators have responded to new developments in museum theory by experimenting with innovative conceptual frameworks to address the politics and poetics of museological representation.1 As the field of anthropology continues to wrestle with its own colonial foundations, the search for ‘decolonizing’ methods has also become a central concern for contemporary ethnographic museums.2 The Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt, the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, and the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC are but a few examples of institutions which, with varying degrees of success, have begun to reflexively incorporate decolonial praxis into their exhibition strategies. Such work has laid critical foundations for challenging essentialist and racist depictions of the ethnographic ‘other’, and for dislodging deeply rooted imperialist hierarchies of categorization, interpretation, and display.

Here I wish to redirect the decolonial gaze toward the archives, catalogues, and storage facilities – spaces where ethnographic objects are first identified and contextualized.3 While the acts of organizing and labeling these items render them scientifically legible and accessible for further research, these activities are ultimately limited, trapping the objects within bounded ideological categories. Historically, rhetorical strategies for comprehending the significance of non-Western materials and life-worlds have alternated between applying ‘scientific’ standards to gauge their research value, and ‘artistic’ criteria to calculate their aesthetic worth.4 How might present-day researchers avoid such binary reductionism as they return to the artifacts that have been sitting for decades (and often centuries) in ethnographic museums? If Western practices of classification prioritize bureaucratic, imperialist forms of knowledge, systematically excluding other worldviews and understandings, how could scholars address the moral and political consequences of these practices, while embracing artifacts’ diverse narratives and corporeal subjectivities?5 How could it be possible to ‘unlearn’ these objects’ given histories, and relate to them as dynamic entities, tied not just to the past but to the continually unfolding present and future?6 How might such expanded approaches to understanding the histories of museum objects help forge alternative paths through the broader projects of anthropological and academic research?

In exploring the potential of ethnographic artifacts to take on new meanings and iterations through their ongoing material processes of becoming, I propose to bend the decolonial project to a slightly different – herein described as ‘counter-colonial’ – angle. As scholars have noted, decolonial curatorial approaches involve reflecting upon the brutal effects of colonialism,7 as well as incorporating competing cultural narratives, including indigenous voices and ideologies, into interpretive work.8 Following Linda Tuhiwai Smith, who argues that decolonizing methodologies must recognize the academic setting as a site of struggle between historically authoritative and disempowered voices,9 I define a counter-colonial museological approach as one that challenges institutional narratives by reclaiming research practices that previously have been used to essentialize and alienate the other, but that also draws upon poetic or artistic tactics to disrupt, and reconfigure its own modes of scientific and academic expression.

Many contemporary artists have been caught up in the ‘archival impulse’ outlined a decade ago by Hal Foster, who critiqued museological histories through evocative upheavals of representational paradigms and novel forms of defamiliarization.10 Such work, however, is primarily regarded as belonging to the artistic domain, rather than that of academic research. Projects by artists such as Renee Green, Maryam Jafri, Georges Adéagbo, Jimmie Durham, Lothar Baumgarten, and Fred Wilson have thoroughly explored the mechanisms of scientific classification and display, poignantly dissecting the colonial origins of the ethnographic museum and archive. However, parallel developments within the context of academia are scarce; as the archaeologist Doug Bailey notes, most academic work attempting to bridge artistic and scholarly boundaries is hindered by the assumption that it must adhere to a scientifically representational logic.11 Yet the more compelling research, he writes, is that which is rooted in academia but explores an entirely new interface of artistic-academic inquiry, one that breaks with the ideas of ‘scientific interpretation and explanation’ as primary scholarly goals,12 and ‘embraces misunderstanding, seeks complexity, and creates what is difficult (perhaps impossible) to digest, explain, or interpret’.13

Such work is urgently needed, for it is the very tensions between adhering to scholarly conventions and pushing the limits of those conventions that can challenge existing hierarchies of legitimacy and lead to radically new forms of knowledge. In this vein, and using my skills as a visual anthropologist, I outline an experimental investigation of a contemporary ethnographic museum collection that operates not through uncovering or translating the meanings behind the objects, but rather by adding new visual, textual, and material layers to them. Instead of explicating or contextualizing these artifacts, this work challenges their established histories through deliberately blurring their outlines and distorting their boundaries. It aims to bypass art/culture dichotomies, dissolve the divisions between art and artifact imposed through the development of specific academic and ethnographic discourses over the past few centuries, and create a new critical form that defies fixed interpretive boundaries. Such a move not only complicates meanings cast through the colonial interpretive lens, it also builds a research agenda that destabilizes the configurations of power and authority that have restricted the scope of what is generally viewed as valid academic practice.

The project that I outline here currently exists in material and conceptual fragments, having taken the form of pilot studies, conference presentations, workshops, and research applications. Consequently, the writing in this article invokes multiple forms of text, images, and objects, as well as existing and imagined configurations of practices, materials, and spaces. Using this work-in-progress as a case study, I consider the implications of combining surrealist-inspired methods of ‘bricolage’ with the emergent museological practice of ‘curature’14 to contribute new counter-colonial means of unsettling and reassembling the ‘entangled inheritance’ of ethnographic archives.15 In mapping out the key conceptual underpinnings, I also evoke wider questions around the underlying academic validity of such endeavors. In line with Tuhiwai Smith’s call for developing ‘alternative knowledges’ to critique colonialism’s analytical tools and cultural formations,16 I examine the risks and possibilities of research that shuttles between the accepted aim of unpacking the stories behind institutional collections of ethnographic artifacts, and the political and artistic questions that arise when constructing new (and sometimes impossible) stories about these objects through affective, evocative, and counter-factual provocations.

Bricolage, Surrealism, and Anthropology

Bricolage is described in contemporary museological literature as a tool for developing new meanings from assemblages of collected materials.17 Yet the concept has a longer anthropological and sociological history. According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, both bricolage and processes of anthropological understanding involve ordering and making sense of the world through specific underlying structures of classification. As the bricoleur’s ‘universe of instruments is closed and the rules of his game are always to make do with “whatever is at hand”’,18 including leftover things from individuals and society, these novel combinations of materials give rise to new objects and material subjectivities. In Michel De Certeau’s sociological framing, bricolage is a form of cultural resistance, involving the subversion of dominant traditions through the processes of salvaging and re-interpreting,19 and is described by other writers as ‘tinkering with and recycling cultural givens’.20

In the 1920s and 1930s, the French surrealists explored the principles of juxtaposition and recomposition through bricolage, collage, and assemblage,21 recontextualizing forgotten and outmoded bits of culture using varied materials and forms. Their work played with indexical codes, appropriating and inverting conventions of scientific documentation to call attention to the notion that reality is made, rather than given. From literary-journalistic texts such as André Breton’s Nadja and Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant, to Brassai’s and Eugène Atget’s poetic realist photographs of Paris, to the pseudo-ethnographic films of Luis Buñuel, the surrealists alternated between ‘cool descriptive exactitude and poetic effusion’22 to record everyday life, but also to reveal the artificiality of practices of representation.23 By adhering to realist techniques – first inspiring belief in these images, then subverting what is ordinarily done with such images – they could provoke a more jarring awareness of the instability of claims to representational truth. As surrealism was as much a political movement as it was an artistic one,24 they also viewed these practices as cultural critique, problematizing the broader ideological assumptions of bourgeois society.25

The Parisian surrealists had a contradictory relationship with the discipline of anthropology, simultaneously reverent and critical of its methods and objects of analysis.26 Surrealist publications and exhibitions frequently drew upon anthropological themes and methodologies, reinterpreting and adapting them to meet their own artistic needs and desires. Many Frenchbased anthropologists and scholars during that era were also active in surrealist and avant-garde circles, including Carl Einstein, Michel Leiris, Paul Rivet, and Marcel Griaule. The journal Documents, founded by the ‘dissident’ surrealist Georges Bataille in 1929, published a provocative mixture of articles by surrealists and experts from European ethnographic museums.27 Challenging conventional categorizations of material culture through fragmentation and assemblage, the journal served as a ‘playful museum’ of cultural criticism.28 In the Parisian museum context, in response to the 1931 Colonial Exhibition, local surrealists collaborated with the French communist party to create a ‘counter-colonial’ protest exhibition critiquing the ethnographic processes of commodification and exoticization.29 Juxtaposing displays of so-called ‘tribal art’ with objects of European art and surrealist ready-mades, the exhibition featured visceral collisions of ‘concrete thing, physical sensation, and disordered logic’,30 aimed at bodily disturbing the viewers and prompting them to question the established workings of the colonial gaze.

This history of surrealist incursions into the field of anthropology, however, is a topic that remains under-explored in current anthropological literature. Over the past decades, a few scholars have invoked surrealist perspectives and methodologies in relation to ethnographic practice;31 more recent work has probed the boundaries between artistic and anthropological practice, analysis, and performance.32 Most of these discussions peaked during anthropology’s ‘writing culture’ debates in the 1980s and early 1990s, when there was a widespread focus on the ways in which reflexive experiments with narrative could expose and contest the social constructions of anthropological knowledge.33 In contemporary scholarship, aside from Julia Kelly’s extensive research in the field of art history,34 the broader implications of the crossovers between surrealist and anthropological forms of inquiry have not been thoroughly examined.35

Curature in the Archive

I propose a return to surrealist legacies, particularly to the notion of bricolage, to reconsider its potential for unsettling the colonial foundations of anthropological collections. I set this historical approach in dialogue with the newer concept of curature, coined by Carolyn Hamilton and Pippa Skotnes36 as an innovative decolonial approach to working with archives. Moving beyond the idea of curating as simply ordering and managing existing collections, Hamilton and Skotnes posit curature as an expanded practice that revisits archives’ colonial histories to reformulate how these histories relate to the contemporary, globalized world. A curative approach acknowledges the authority and power accompanying the practice of handling collections, and interrogates these forces through experimenting with novel material arrangements, juxtapositions, and connections.

As a form of ‘recuperative care’,37 curature critically evaluates the archival potential of collected images, objects, and texts, as well as the material culture of curatorial work itself.38 Through enacting new approaches to the standard activities of labeling, photographing, inscribing, digitizing, and exhibiting, a curative methodology appropriates these practices to reformulate a collection’s significance. It proposes that archival artifacts be read not only through their cultural histories (looking at objects as sources of information), but also by foregrounding their corporeal and affective qualities. Archival encounters may, thus, be re-conceptualized as phenomenological experiences, involving embodied and sensory means of reconfiguring historical and colonial narratives.39

In imagining a museum system that treats its possessions as diasporic, composed of discursive, material, and sensory elements, curature also intersects with assemblage theory, relocating the idea of agency from individual acts and things to distributions across collectives.40 Through developing surrealist-inspired practices of curature in the archives, and employing new visual and textual interpretive approaches, the researcher may become an ‘assembleur’, experimenting with form using a contained body of content. The speculative and unpredictable nature of such work contributes to unsettling the authoritative position of the ethnographic researcher. As George Marcus and Erkan Saka write, the ‘time-space [of assemblage] is inherently unstable and infused with movement and change’;41 while this practice dismantles interpretive hierarchies, it simultaneously builds up alternative taxonomies, opening up space for other, decolonizing stories to unfold.

Cataloguing Culture

The study I outline here developed as a collaboration between my work as a social and visual anthropologist, and that of Selena Kimball, a multi-media artist based in New York. Over the past decade, we have conducted a number of art-anthropology projects, resulting in texts, films, and installations.42 As groundwork for our current research on museum archives,43 we conducted a pilot study using a randomly selected ethnographic museum catalogue as our source material. The catalogue, Being Object, Being Art: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Museum of World Cultures, Frankfurt am Main44 was part of an exhibition of the same title, which ran from 2009–10 at the Frankfurt Weltkulturen Museum.45 The catalogue features 130 artifacts from Africa, Oceania, the Americas, and East and Southeast Asia, including woodcarvings, metal sculptures, textiles, gourd vessels, headdresses, and leather figurines. These objects are portrayed in glossy color photographs, surrounded by dramatic halos of light that emphasize their formal details and elaborate craftsmanship. A passage of contextualizing commentary accompanies each image, containing information about the objects’ materials, manufacturing techniques, conditions of acquisition, and significance within their communities of origin.

The book’s promotional blurb claims that the goal of this exhibition was to ‘undermine’ traditional ethnographic designations of objects, and instigate new means of reading them as both anthropological artifacts and artistic pieces.46 As the Weltkulturen Museum’s website explains, ‘[T]he beholder is meant to discover the extraordinary, the elaborate, the different, the perfect, the harmonic or even the disturbing in the objects concerned’.47 The actual exhibition featured an additional room with pieces by contemporary ‘artists of the so-called diaspora’,48 but the printed catalogue does not include this work. Its text explicitly locates the museum at the forefront of debates on the ‘status of ethnic artifacts’, arguing that the exhibition and resulting publication address a central concern to ‘reorient the taxonomies of [the museum’s] collections’.49 Presumably construed as a corrective to existing discussions about non-Western objects that use ‘either/or’ language to distinguish between the artistic and the ethnographic, the website states that the exhibition’s curators embrace the more inclusive language of ‘as well as’ to confirm the objects’ membership in both artistic and anthropological worlds.50

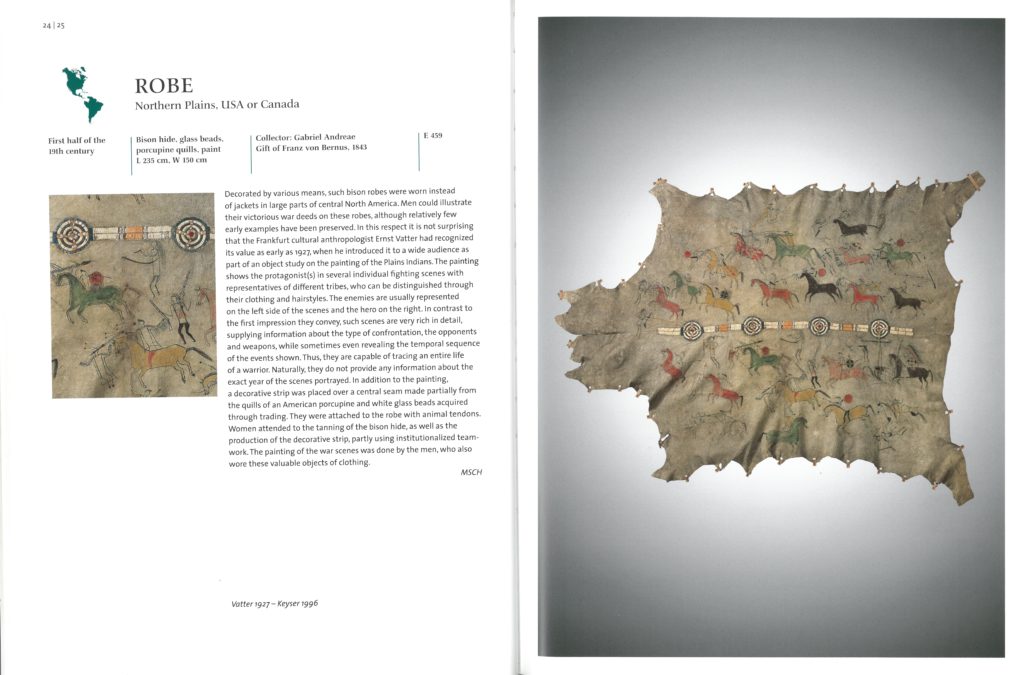

‘Robe: Northern Plains, USA or Canada’, collected by Gabriel Andreae, gift of Franz von Bernus, 1843, image from Being Object, Being Art: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Museum of World Cultures, Frankfurt am Main, ed. Achim Sibeth (Tübingen: E. Wasmuth Verlag, 2010), photo: Stephan Beckers, Frankfurt am Main, 2009; image courtesy of Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

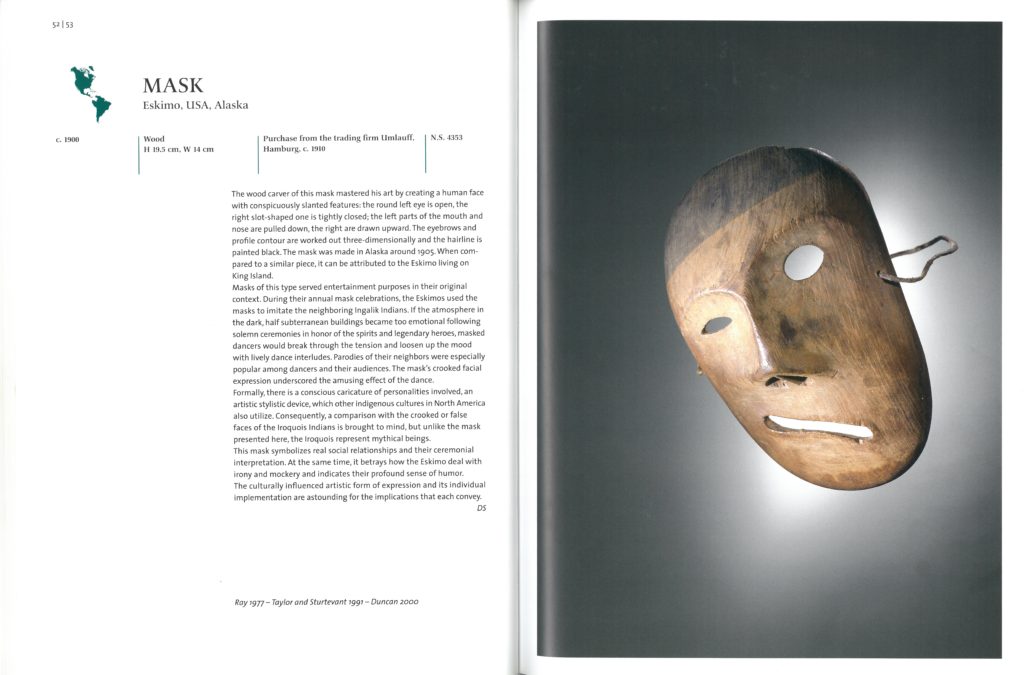

‘Mask: Eskimo, Alaska, USA’, purchased from trading company Umlauff, 1910, image from Being Object, Being Art: Masterpieces from the Collection of the Museum of World Cultures, Frankfurt am Main, ed. Achim Sibeth (Tübingen: E. Wasmuth Verlag, 2010), photo: Stephan Beckers, Frankfurt am Main, 2009; image courtesy of Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

The move to reframe these objects as simultaneously ‘artifact’ and ‘art’ can be read as a response to anthropology’s long history of dividing material culture into artistic versus cultural taxonomies of categorization. As James Clifford outlined in his classic book, The Predicament of Culture,51 until the 19th century, Europeans primarily classified tribal objects as either ‘antiquities’ or ‘grotesques.’ By the early 20th century, they had begun defining these objects as valuable ‘cultural witnesses’ (according to relativist anthropologists), or as fine examples of ‘primitivist art’ (according to modernist scholars and art experts). Subsequently, as Clifford argued, the framing of ethnographic artifacts alternated between the mutually exclusive categories of the ‘authentically cultural’ or the ‘authentically artistic’.52 By advocating a hybrid framework that recognizes cultural artifacts as legitimate works of art, the Weltkulturen Museum curators are attempting to bridge this dichotomy and thereby create new taxonomical possibilities.

Having become a high-profile anthropological institution in recent years, this museum has experimented broadly – and somewhat controversially – with the role of art and art practitioners within the ethnographic context.53 In many ways the museum has both challenged and amplified standard practices of anthropological interpretation. In the case of this catalogue, however, the presentation of the objects as both art and artifact collapses these two categories without critically deconstructing how they might be mutually constituted through specific modes of representation and display.54 It additionally overlooks the underlying cultural assumptions of artistic practices themselves.55 By labeling its ethnographic artifacts ‘artistic masterpieces’, the Being Object, Being Art rhetoric continues to appropriate and exoticize the ‘things, facts, and meanings’56 of the ethnographic other, ultimately reasserting the museum’s institutional power to define artifacts of indigenous cultural production in persistently Western terms.

Yet such objects need not be gathered under the single umbrella of cultural artifacts and contemporary art, as the Weltkulturen Museum catalogue suggests. What would happen if we gave them space to become neither cultural artifacts, nor works of contemporary art, but something else entirely? What could an artifact do or say if it defied such categorizations? Returning to Clifford,57 he suggested understanding ethnographic objects not as cultural signs or as artistic icons, but as deeply personal, non-exoticized fetishes. As he noted, instead of expecting museum objects to edify and inform us, recognizing them as fetishes allows us to acknowledge their power to disconcert us through their very resistance to classification, thereby making us more attuned to the constructed and arbitrary ways in which we attempt to define and set order to the unknown.

The concept of the fetish has captivated the intellectual imagination for centuries; as a subject of investigation into non-Western religious belief systems, classical anthropologists defined fetishism as the ‘primitive’ idea that spirits could take up residence in inanimate material objects, endowing them with living souls.58 Many French surrealists also viewed artworks as fetishistic, describing their sculptures and assemblages as objectifications of the living, dynamic qualities of memory and desire.59 Drawing on surrealist-psychoanalytic interpretations of material culture, as well as Roland Barthes’ semiotic concepts of the fetish as an item ‘of strictly personal meaning unformed by cultural codes’,60 Clifford proposed this alternative take on museum artifacts as a viable direction for the future, though he offered no suggestions for how this might play out in practice. Since the publication of his text thirty years ago, this possibility has not been seriously examined, at least not in the literature on museum anthropology. In the passages below, I discuss how my collaborative work with Kimball takes up this challenge, not by claiming to produce ‘artistic interpretations’ of ethnographic artifacts, but by materially confounding and complicating these artifacts’ classificatory and explanatory potentials, while still remaining rooted within an ethnographic/archival/academic framework.

A ‘Curative’ Bricolage

If we return to the artifact pictured in Figure 1, the text identifies it as a robe of the Northern Plains Indians, made in the early 19th century. The text describes the object as manufactured from bison hide, glass beads, porcupine quills, and paint. It explains the imagery as depicting fighting scenes between the ‘protagonists’ and ‘enemy tribes’. It informs us that the paintings convey important information about weapons, confrontations, and the lives of warriors. We learn that the women performed the work of tanning the bison hides, while the men were the ones to paint the war scenes. We also find out that the ‘value’ of this type of robe was recognized by the German anthropologist Ernst Vatter, who ‘introduced it to a wide audience’ in 1927, thereby helping to spread knowledge about the Plains Indians.

The text in Figure 2 is written in much the same tone. It identifies the piece in the photograph as a wooden Eskimo mask from Alaska, made around 1905 and purchased by a German trading firm in 1910. The voice is didactic and informational, offering visual and formal evaluations of the piece, as well as outlining its social functions. We are told that the mask ‘symbolizes real social relationships’ and that it reveals how the Eskimos deal with issues such as irony and mockery. At the same time the narration betrays value judgments that go beyond objective facts, praising the mask’s ‘astounding’ artistic form of expression, and revealing its connections to the Eskimos’ ‘profound sense of humor’.

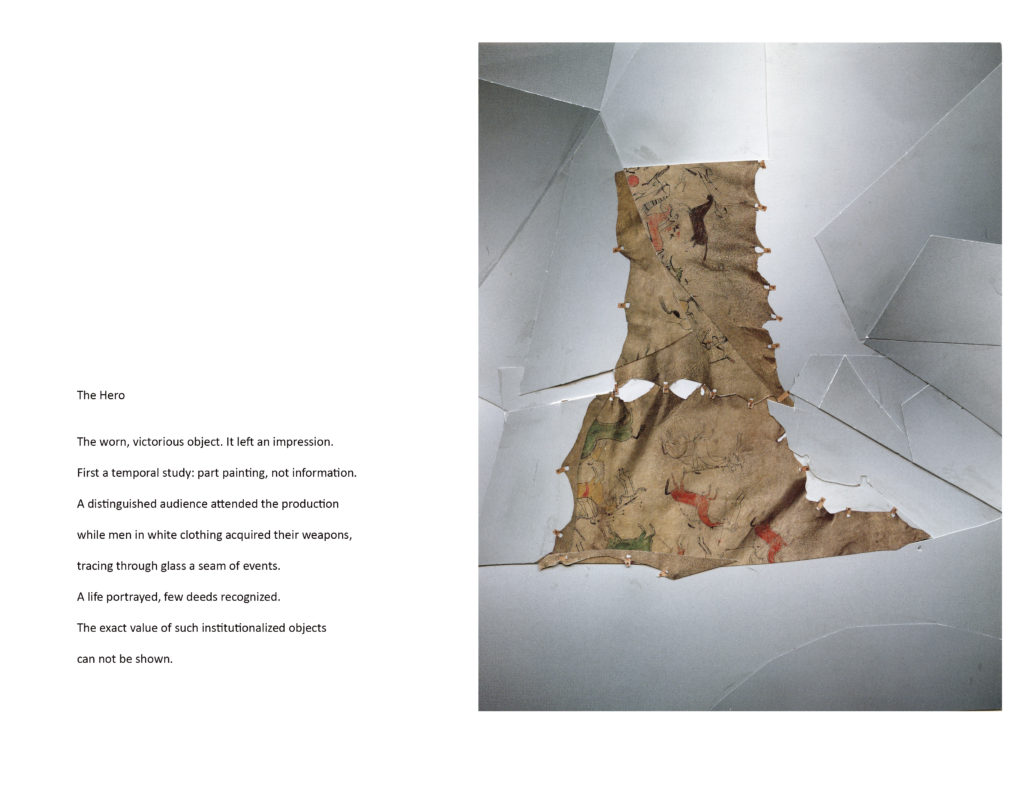

In our treatment of these anthropological documents, Kimball and I followed a simple set of practical guidelines. Kimball began by literally cutting up the image of the object, in a similar way that she would cut up any other material she works with in her broader practice of collage. Using scissors and glue, she then reassembled parts of this material into an image of a new artifact. In response to her object, I cut up the original explanatory text, and reassembled a selection of these words into a text that referenced the new object (see Figures 3 and 4 below). In using the original text as my raw material, I treated the written narratives in the catalogue not just as sources of historical or scholarly information, but as physical found objects in and of themselves.61

Each new visual and textual work that we produced was to consist only of elements from the original materials; no new words or images were to be added. Kimball transformed the bison robe into a patchwork of painted hide with a vaguely animalistic bearing, its two hollow eyes positioned against a background of fractured shadows. My text, entitled The Hero, reads:

The worn, victorious object. It left an impression. First a temporal study: part painting, not information. A distinguished audience attended the production while men in white clothing acquired their weapons, tracing through glass a seam of events. A life portrayed, few deeds recognized. The exact value of such institutionalized objects cannot be shown.

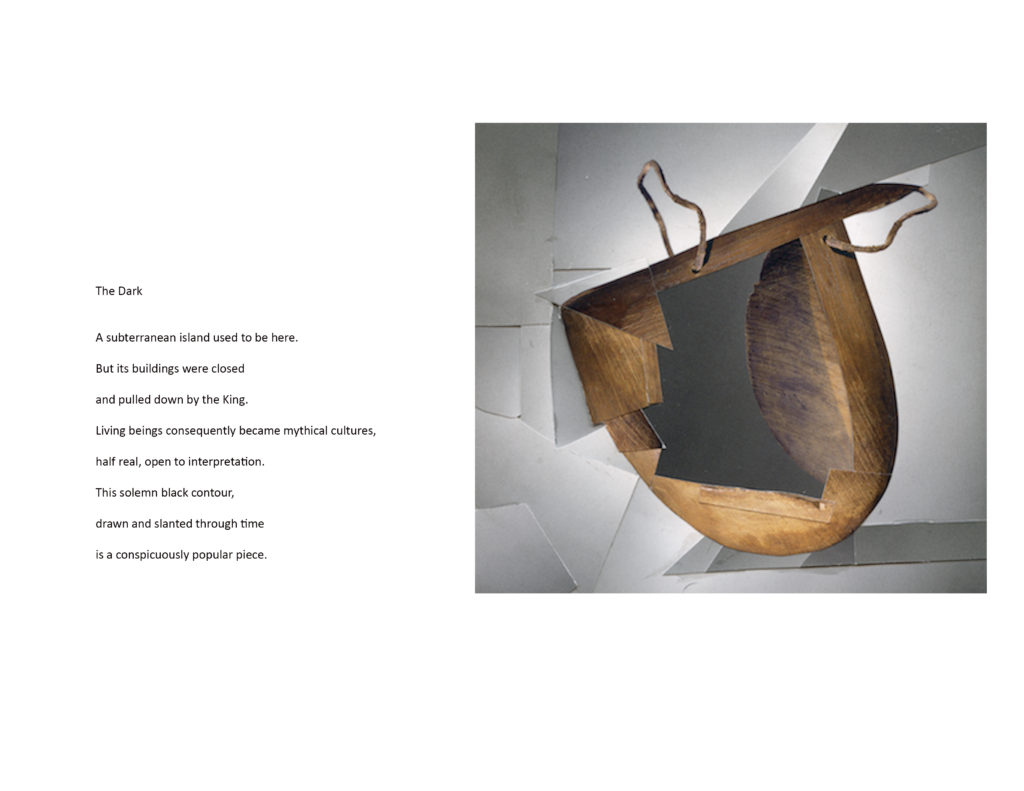

Kimball turned the photograph of the mask into an image of a cavernous frame, precariously balanced on one rounded edge, hinting at the existence of other worlds beyond its external surface. My accompanying narrative, entitled The Dark, reads:

A subterranean island used to be here. But its buildings were closed and pulled down by the King. Living beings consequently became mythical creatures, half real, open to interpretation. This solemn black contour, drawn and slanted through time, is a conspicuously popular piece.

Resisting Classification

Using only the images and words from the museum catalogue to create new objects and narratives, Kimball and I assume the role of bricoleurs, experimenting with form using a self-contained body of content. By combining this practice with principles of curature, we create a counterpoint to the suggestion that the objects in this collection should be defined in solely ‘scientific’ and/or ‘artistic’ terms. In this framework, artifacts can no longer be slotted into the categories of either ‘scholarly’ research material, or ‘creative’ forms of craftsmanship. Through turning photographs of artifacts and their interpretive narratives into semi-fictional objects and accounts, unchaining the collected specimens from their previously assigned descriptive labels, we propose an archival inventory that rejects naming these items according to standardized facts and knowledge, obfuscates their given social and historical trajectories, and hints at subjective, provocative, and counter-factual stories.

As the Surrealists long ago noted, destabilizing and altering the established functions of an object can provoke disorder and confusion, giving the object a certain fetishistic power and causing a crisis in the nature of experience. The capacity of fetishes to propel the body to grapple viscerally with their presence points to their disruptions not merely as cognitive acts, but as contributions to new affective and sensory states. According to the surrealists, such incitements of dream-like emotional and physical states give rise to new kinds of socio-political awareness, as well as space for imagining alternative (counter-colonial) cultural orders. Returning to these ideas nearly a century after they were first proposed is not so much an attempt to resurrect fixed formulas from a static past, but rather an exploration of how to incorporate politically grounded artistic concerns into new dialogues with contemporary cultural configurations and curatorial theories. In addition, broadening the scope of the Surrealists’ original focus lays important groundwork for the further development of novel forms of anthropological research and practice.

Selena Kimball (image) and Alyssa Grossman (text), The Hero, 2015, collage (paper on paper), 18.5 cm x 14.5 cm, image courtesy of Selena Kimball and Alyssa Grossman.

Selena Kimball (image) and Alyssa Grossman (text), The Dark, 2015, collage (paper on paper), 12cm x 13 cm, image courtesy of Selena Kimball and Alyssa Grossman.

As noted above, this collaboration currently takes the form of an evolving pilot study, an emerging blueprint to be developed in a number of potential directions. As we continue to produce an expanded series of collage objects and texts, Kimball and I will collate this work into its own ethnographic catalogue, presenting a collection of unlikely things and narratives as legitimate (albeit non-existent) artifacts of research. As another output of the endeavor of curature, this publication would not only reframe museum discourses and recast colonial legacies, but also question the genre of the academic exhibition catalogue itself. Through adhering to certain research protocols and accepted formulas of museological presentation, yet also deliberately making those formulas strange and unfamiliar, it will highlight the complexities and contradictions inherent in a product commonly assumed to contain traditionally ‘valid’ scientific accounts. Neither a work of art, nor an ‘output’ of scientific research, the project as a whole resists attempts to label or categorize its form, function, and meaning. Through eluding the conventional mechanisms of academic evaluation, we wish to compel viewers to reconsider their own perceptions of both the affective value and the scholarly significance of artifacts drawn from colonial contexts.

Although the work described here risks being read as a formal exercise in visual and textual collage, rather than a social and cultural critique of normalized museum conventions, this is precisely why it is essential to keep such a project rooted within the academic domain and in dialogue with ethnographic and museum researchers – so that anthropologists, archivists, curators, and their publics can continue to reflexively examine their practices, and develop new possibilities for the forms and methodologies of scholarly practice and knowledge production. In countering expectations that an ethnographic catalogue should offer explanatory or comprehensive histories to its readers, our work challenges assumptions that the tasks of curators and anthropologists should primarily be to clarify, illuminate, and instruct. While some might question the decision to distance these particular museum artifacts from the data serving as longstanding scientific records of their (colonial) identity, this strategy shifts the source of authority from seemingly fixed archival ‘facts’ to an emerging and fluid repository of materials that do not answer to the usual terms of institutional validity. Such an approach opens up the potential for objects of colonial inquiry to take on Clifford’s role as disconcerting fetishes, which defy established modes of categorization and become part of an evolving set of material encounters in the present.

In the contemporary framework of global controversies surrounding the politics of artifact repatriation, restitution, and access to digitized collections, there is a pressing demand for novel approaches to museum decolonization. As unprecedented numbers of people and objects are currently moving precariously across national boundaries, the need to reconsider the relationship between ethnographic collections and their source communities has become an even greater moral imperative. While it is essential to continue the development of curatorial methods critiquing the institutional power structures and political mechanisms behind the processes of collection and display, new terms for research must be considered within the post-colonial archival context. Through reassembling ethnographic materials in ways that highlight their resistance to conventional classificatory schemes, and by proposing counter-factual, surrealist-inspired interfaces with archival realms, this project breaks with the traditional academic drive toward scientific explanation, in order to reframe ways of engaging with the entangled issues of cultural heritage, colonial history, and curatorial and anthropological processes of interpretation.

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to the editors and reviewers of OAR for their insightful and detailed feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I am grateful to the Frankfurt Weltkulturen Museum for permission to reprint images and texts from their exhibition catalogue. Thanks also to John Brode, for his comments on the text, and to Selena Kimball, for her longstanding contributions to our collaborative work and its theorization.

1. See Luca Basso Peressut, et al., European Museums in the 21st Century: Setting the Framework, Vol. 1 (Milan: Mela Books, 2013); Sharon Macdonald and Paul Basu, eds., Exhibition Experiments (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007).

2. See Felicity Bodenstein and Camilla Pagani, ‘Decolonising National Museums of Ethnography in Europe: Exposing and Reshaping Colonial Heritage (2000–2012),’ in The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History, ed. Iain Chambers, et al. (London: Ashgate, 2014); Annie Coombes and Ruth Phillips, ‘Introduction: Museums in Transformation, Dynamics of Democratization and Decolonization,’ in The International Handbook of Museum Studies, Vol. 4: Museum Trans formations, ed. Sharon Macdonald, et al. (London: Wiley Blackwell, 2015); Klas Grinell and Lotten Gustavsson Renius, ‘The King is Dead. Long Live the King! Uninheriting Modern Ethnography While Inheriting Objects of Ethnography,’ in Beyond Modernity: Do Ethnographic Museums Need Ethnography?, eds. Sandra Ferracuti and Elisabetta Frasca (Rome: Espera, 2013); Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

3. For discussions of the ethnographic catalogue and other storage mechanisms shaping the frameworks of museum display, see Fritha Langerman, ‘Cover to Cover: The Contribution of the Book to the Reproduction of Linear, Hierarchical Models of Natural History,’ in Uncertain Curature: In and Out of the Archive, eds. Carolyn Hamilton and Pippa Skotnes (Johannesburg: Jacana Press, 2014); Hannah Turner, ‘Decolonizing Ethnographic Documentation: A Critical History of the Early Museum Catalogs at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History,’ Cataloging and Classification Quarterly 53 (2015): 658–76; Nancy Parezo, ‘The Formation of Ethnographic Collections: The Smithsonian Institution in the American Southwest,’ Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 10 (1987): 1–47.

4. For an in-depth discussion of this ‘art-culture system’, see James Clifford, ‘On Collecting Art and Culture,’ in James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988): 94–107.

5. See Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star, Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), and Martha Lampland and Susan Leigh Star, eds., Standards and Their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

6. Madina Tlostanova and Walter Mignolo, Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2012).

7. Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums.

8. Daniel Cull, ‘Subjectivity as Treatment: Neurosis and the Roots of Contemporary Ethnographic Conservation,’ Conservation, Exposition, Restauration D’Objets d’Art 4 (2009); Claire Wintle, ‘Decolonizing the Museum: The Case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes,’ Museums and Society 11:2 (2013): 185–201.

9. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2006), 39.

10. Hal Foster, ‘An Archival Impulse,’ October 110 (2004): 3–22.

11. Doug Bailey, ‘Art//Archaeology//Art: Letting-Go Beyond,’ in One World Archaeology II: Collaborations, Conversations, Criticisms, eds. Ian Russell and Andrew Cochrane (New York: Springer, 2014), 246. Some examples of such work cited by Bailey include a project by the archaeologists Christopher Tilley, Barbara Bender, Sue Hamilton, as well as work by the artist and archaeologist Aaron Bender

12. Doug Bailey, ‘Art//Archaeology//Art,’ 241.

13. Idem, 235.

14. Hamilton and Skotnes, Uncertain Curature.

15. Idem, 22.

16. Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 34.

17. See Anwar Tlili, ‘Encountering the Creative Museum: Museographic Creativeness and the Bricolage of Time Materials,’ Educational Philosophy and Theory 48:5 (2016): 443–58.

18. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 11.

19. Véronique Altglas, ‘“Bricolage”: Reclaiming a Conceptual Tool,’ Culture and Religion 15:4 (2014): 475.

20. Anna Dezeuze, ‘Assemblage, Bricolage, and the Practice of Everyday Life,’ Art Journal 67:1 (2008): 34.

21. ‘Collage’ refers to aggregations of two-dimensional materials, practiced since the advent of papermaking as early as 200 BC, but was not specifically coined as an artistic term until the early 1900s. ‘Assemblage’ involves the combination of three-dimensional found, bought, and made objects, first developed by the Dadaists and surrealists in the early 20th century. See Emily Bell, ‘Collage,’ The University of Chicago:: Theories of Media:: Keywords Glossary:: (2007), accessed 1 July, 2017 at http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/collage.htm.

22. Ian Walker, City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 12.

23. See also Linda Williams, Figures of Desire: A Theory and Analysis of Surrealist Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981).

24. In the First Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, André Breton wrote that one of surrealism’s primary concerns was to undermine positivism, emancipate the imagination, and ‘liberate humanity from the ideological shackles that enforce the contradiction between dream and waking life’, see: Franklin Rosemont, André Breton and the First Principles of Surrealism (London: Pluto Press, 1978), 20–21. Influenced by Marxist politics, Freudian psychoanalysis, and German and occult philosophy, the early surrealists viewed the realms of ‘poetry, dreams and unconscious life [as containing] solutions to the gravest problems of human existence’, see idem, 24.

25. Michael Richardson, ‘An Encounter of Wise Men and Cyclops Women: Considerations of Debates on Surrealism and Anthropology,’ Critique of Anthropology 13:1 (1993): 58.

26. Julia Kelly, Art, Ethnography and the Life of Objects, Paris c. 1925–1935. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012).

27. Julia Kelly, ‘Discipline and Indiscipline: The Ethnographies of Documents,’ Papers of Surrealism 7 (2007): 1–20.

28. James Clifford, ‘On Ethnographic Surrealism,’ Comparative Studies in Society and History 23:4 (1981): 551.

29. Janine Mileaf, ‘Body to Politics: The Surrealist Exhibition of the Tribal and the Modern at the Anti-Imperialist Exhibition and the Galerie Charles Ratton,’ Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 40 (2001): 239–55.

30. Idem, 251.

31. In ‘The Modernist Sensibility in Recent Ethnographic Writing and the Cinematic Metaphor of Montage,’ Visual Anthropology Review 6:1 (1990): 2–12, George Marcus cites Michael Taussig’s Colonialism, Shamanism, and The Wild Man as an example of an ethnography that makes use of montage to approximate the effects of shamanic performance. In The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), Paul Stoller describes the surrealist influences of improvisational methodologies and the fusion of art and science in Rouch’s films.

32. See recent work by Michael Taussig, including The Corn Wolf (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), which experiments with poetic dimensions of ethnographic storytelling; see also projects by Annie Danis and Annie Malcolm at Unive risty of California, Berkeley; Lucy Suchman and Laura Watts at Lancaster University; and Joe Dumit’s work at University of California, Davis.

33. For example, see Vincent Crapanzano, Tuhami: Portrait of a Moroccan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); Dennis Tedlock, The Spoken Word and the Art of Interpretation (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983); and Marjorie Wolf, A Thrice Told Tale: Feminism, Postmodernism, and Ethnographic Responsibility (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992).

34. See Kelly, ‘Discipline and Indiscipline’; Kelly, Art, Ethnography and the Life of Objects; and, Julia Kelly, ‘The Ethnographic Turn,’ in A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, ed. David Hopkins (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

35. Related work, such as Clifford, ‘On Ethnographic Surrealism’, Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), Roger Sansi, Art, Anthropology and the Gift (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), and Stoller, The Cinematic Griot has largely remained at the margins of contemporary mainstream anthropological debates.

36. Hamilton and Skotnes, Uncertain Curature.

37. This phrase ‘recuperative care’ could be put into dialogue with ‘reparative knowing’, described in Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Knowing: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003): 150–51, which she defines as critical, communal, intertextual discourses that ‘succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture – even of a culture whose avowed desire has often been not to sustain them’.

38. Hamilton and Skotnes, Uncertain Curature, 9.

39. See Sandra Dudley, ‘Museum Materialities: Objects, Sense and Feeling,’ in Museum Materialities: Objects, Engagements, Interpretations, ed. Sandra Dudley (London: Routledge, 2010), and Janice Baker, Sentient Relics: Museums and Cinematic Affect (London: Routledge, 2017).

40. Rodney Harrison, ‘Reassembling Ethnographic Museum Collections,’ in Reassembling the Collections: Ethnographic Museums and Indigenous Agency, eds. Rodney Harrison, et al. (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2013).

41. George Marcus and Erkan Saka, ‘Assemblage,’ Theory, Culture and Society 23:2–3 (2006): 102.

42. See Alyssa Grossman and Selena Kimball, ‘The Memory Archive: Filmic Collaborations in Art and Anthropology,’ Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 9:1 (2009): 1–38; Alyssa Grossman, ‘Forgotten Domestic Objects: Capturing Involuntary Memories in Post-communist Bucharest,’ Home Cultures 12:3 (2015): 291–310.

43. In 2017, I submitted an application to the Swedish Research Council to develop a related project within the archives of the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden.

44. Achim Sibeth, ed., Being Object, Being Art: Masterpieces From the Collections of the Museum of World Cultures, Frankfurt/ Main (Tübingen: E. Wasmuth Verlag, 2010).

45. Kimball first found the catalogue in a second-hand bookstore in New York, and suggested we use it as material for our collaboration, knowing nothing at the time of the history of the Weltkulturen Museum, or that I had been reading about its recent experiments in artistic-anthropological curatorship.

46. See: http://www.artbook.com/9783803033383.html, accessed 1 July, 2017.

47. See: http://www.weltkulturenmuseum.de/en/ausstellungen/archiv/56?page=3, accessed 1 July, 2017.

48. Stefan Eisenhofer, ‘Being Object. Being Art: Masterpieces from the Collections of the Museum of World Culture (Frankfurt am Main),’ African Arts 44:1 (2011): 83.

49. See: http://www.artbook.com/9783803033383.html, accessed 1 July, 2017.

50. See: http://www.weltkulturenmuseum.de/en/ausstellungen/archiv/56?page=3, accessed 1 July, 2017.

51. Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, 103.

52. Ibidem.

53. See Clémentine Deliss, ed., Object Atlas: Fieldwork in the Museum (Frankfurt Am Main: Weltkulturen Museum, 2012).

54. For a detailed discussion of this topic in relation to surrealist sculptural work, see Julia Kelly, ‘The Found, the Made, and the Functional: Surrealism, Objects and Sculpture,’ in Found Sculpture and Photography from Surrealism to Contemporary Art, eds. Julia Kelly and Anna Dezeuze (New York: Ashgate, 2013).

55. This is a critique that has been leveled at the Weltkulturen Museum in broader terms; see for example Haidy Geismar, ‘The Art of Anthropology: Questioning Contemporary Art in Ethnographic Display,’ in The International Handbooks of Museum Studies: Museum Theory (1st ed.), eds. Andrea Witcomb and Kylie Message (West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, 2015).

56. Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, 98.

57. Idem, 104.

58. See Hartmut Böhme, Fetishism and Culture: A Different Theory of Modernity, trans. Anna Galt (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014).

59. See Kelly, Art, Ethnography and the Life of Objects.

60. Clifford, The Predicament of Culture, 105.

61. As Hamilton and Skotnes note, while labels are often overlooked as archival objects, they are as much a part of the material culture of museum practice as any collection of artifacts or images, and should be acknowledged as such, see: Hamilton and Skotnes, Uncertain Curature, 9.