Art and Criminology of the Border: The Making of the Immigration Detention Archive

Mary Bosworth and Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll

To cite this contribution:

Bosworth, Mary, and Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll. ‘Art and Criminology of the Border: The Making of the Immigration Detention Archive.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 1 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/art-criminology-border-making-immigration-detention-archive/.

Introduction

This article describes a cross-disciplinary art project based at the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford, in which the two authors came together to create and work with items produced by immigration detainees. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll joined Mary Bosworth on a year long residency in July 2015 to work with and extend the immigration detention archive that Mary had established in 2013. She ran film and Photoshop classes for detainees, took documentary photographs, video and sound, digitised and catalogued the growing archive at Oxford. Khadija also made a short film using interviews, paperwork and drawings from the collection, and wrote and directed a play inspired by it.

Gathered together as a physical collection, the immigration detention archive contains a range of items including detainee drawings, paintings, papier mâché and mudrock models, origami and jewelry, and documentation. In addition to pieces produced by staff and detainees, the collection includes photographs and fieldnotes made by a small group of researchers directed by Mary. It is part of an on-going long-term research project on everyday life in immigration detention that commenced in 2009, when Mary first obtained permission to enter these sites. Since that time, she has remained the only academic in the UK who is allowed to enter them freely. She is able to extend this access to students and researchers working with her.1

1. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Media Room with trompe-l’oeil of London skyline in Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre, 2015, digital photograph, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

1. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Media Room with trompe-l’oeil of London skyline in Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre, 2015, digital photograph, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

The Context

At the time of writing, around 3500 men and women are held each day in one of nine Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs, which are also referred to as detention centres, removal centres and deportation centres) scattered across the UK.2 Most IRCs are located in the South East of the country, clustered around the two main airports of London. An additional sum of people may be held for brief periods in Short Term Holding Facilities (STHFs), many of which are located in ports and airports. They may also be confined in police stations, mental hospitals and in holding rooms in any Asylum reporting centres. Finally, those who have completed a prison term may be held post-sentence in prison, under Immigration Act powers, until they are either released, deported, or relocated to an IRC.

Although there is a national immigration detention system, there is no sole national provider. Rather, the Home Office contracts out the management of these sites of confinement to different providers. At the time of writing, there are five different custodial businesses running these institutions: HM Prison Service, Mitie, GEO, G4S and Serco.

Foreign citizens may be detained following a prison sentence, or for an immigration violation such as overstaying their visa or entering the country without papers. They may also be detained for identification purposes, or while their asylum claim is underway. The vast majority of those detained (90%) are men, and most are from former British colonies or sites of recent conflict. The top five nationalities of those leaving detention in March 2016 were: Pakistan, India, Albania, Bangladesh and Nigeria.3

One of the defining characteristics of the British detention system is that, unlike the rest of the EU, there is no statutory upper limit to the period for which a person can be detained, unless they are pregnant or if they are under 18 and held with their parents. Members of those protected groups can only be held for 72 hours, or, with Ministerial approval, for as long as a week. Although the vast majority of people are either removed or released within four months, and indeed the majority of them go much sooner, each centre houses people for much longer.4

In part because of the uncertain duration of detention, IRCs run a limited regime of activities. In a system where around half the occupants leave within a month, it can be difficult to plan a series of sustained workshops or events. Language and cultural barriers, as well as the high levels of anxiety and depression exhibited by the population, can all be obstacles to their participation. Such matters are further compounded by cost-cutting exercises and, most crucially, by the logic of a system of expulsion. If detainees are destined for elsewhere (even when 50% are not removed), it is difficult to justify spending public funds on their education, work or training.

Under these circumstances, IRCs have developed a pared-down provision of services, offering access to the internet, gym, English as a second language, and art and craft. Most also have a ‘cultural kitchen’, which detainees can book to spend time together to cook their own food. There are usually some limited opportunities for paid work, in cleaning or serving food, while some centres are experimenting with offering limited online qualifications in a restricted number of educational offerings.

For staff and detainees, the lack of activities and the rapid turnover of the population is boring and painful. For the researcher, it can be challenging.5 Gaining trust is particularly difficult, compounded by linguistic barriers and cultural differences. Detainees often have poor mental health, and rates of depression are extremely high.6

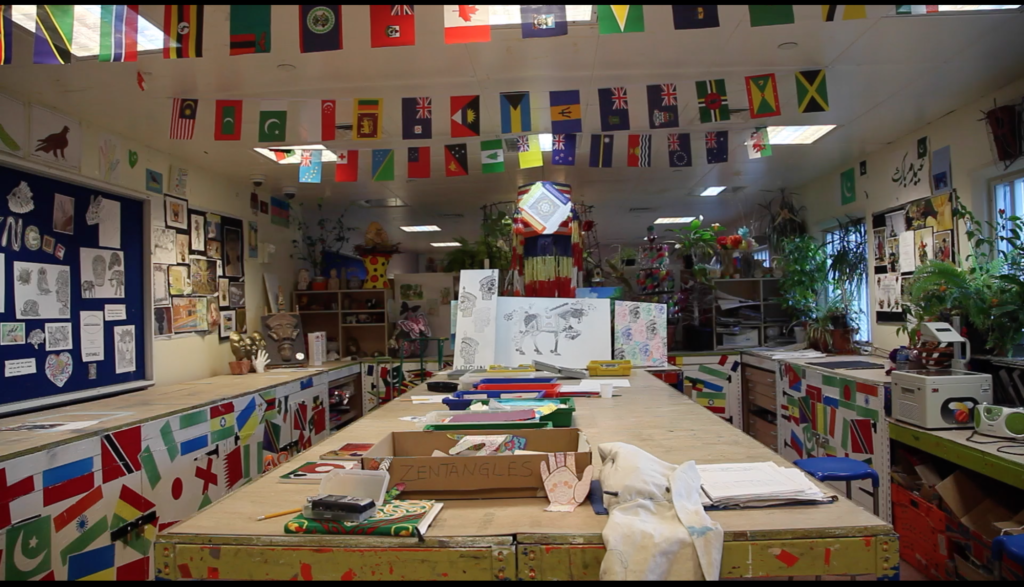

It is common practice in custodial research to spend time in the education block. These areas, which, in detention, include the art and media rooms (Fig. 1 and 2), are usually somewhat more relaxed than elsewhere in the institution. They may be staffed by ‘civilian’ teachers, or by officers who advocate a more ‘rehabilitative’ or ‘therapeutic’ approach to custody, than their more security-concerned colleagues. The archive has its roots in this aspect of research, as Mary gravitated towards the art rooms as places where she could have quiet conversations in a more relaxed environment.

2. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Art Room of Campsfield House, 2015, video still from Artists in Residence, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

2. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Art Room of Campsfield House, 2015, video still from Artists in Residence, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

Art Rooms in Immigration Detention

Although all IRCs have art rooms, they vary somewhat in their provision and instruction. The two that were most important for this project were located in Campsfield House, outside Oxford, and Colnbrook, adjacent to Heathrow Terminal 5. Whereas Campsfield House employs a full-time, trained art teacher, Colnbrook predominantly relies on the labour of a selection of detainee custody officers. The teacher at Campsfield House emphasises artistic methods, while Colnbrook has a range of equipment for media and music, much of which is under-utilised. At the time of the research, the part-time art teacher in Colnbrook largely offered the men colouring pencils, as well as access to a sewing machine.7

The art room is more purgatory than Zen in its décor. Swathed in flags from the multicolour of nationalities and poorly affixed artworks, this has horror vacui: the fear of emptiness expressed by filling entire surfaces with drawings. The effect is not calming, and is amplified by the noisy radio and din of different conversations echoing over the cheap partition walls.

Nevertheless, detainees speak approvingly of these spaces. The materials provided seem to absorb at least some of their free-floating fears. Some can lose themselves in the details of their project, relaxing from the anxieties of their immigration case. The rhetoric of redemptive self-improvement justifies these sites, even as their staff are often the first to be deployed when problems arise elsewhere.

The images and artefacts in the archive challenge the traditional divide between modernist definitions of artistic freedom (which also underpins ideas in art therapy), and the culturally embedded practises of crafting gifts. The Oxford collection began with a bunch of origami flowers and a large swan given to Mary by women in the Yarl’s Wood Centre, followed a ring and some birds she made in the art room at the Tinsley House centre. Such items predominate in these spaces, where most participants turn their hand at craftwork for the very first time. Unused to ‘spare’ time, or ‘leisure’, people in detention turn to activities they may have never done before, or left long ago in their childhood. While most of them are untrained, they are sometimes joined by craftsmen, jewellers, or weavers, who had sought new opportunities in Britain, away from the tasks of their fathers and their fathers’ fathers. Still others, just a handful, are academically trained.

A striking example in the archive can be found in the work of one Chinese man who was held in Campsfield House Immigration Removal Centre. While writing this piece, we struggled to reconcile the conventions of our two disciplines, namely criminology and art practice and thory. His case in many respects captures the potential and the tension in this kind of cross-disciplinary project. For Mary, his name had to be withheld, as we had not obtained his permission to use it, because he had already been deported. For Khadija, naming him returned him his agency, lost by his confinement, honouring him as an artist, rather than ‘another research subject’. As a compromise, we settled on the first part of his name, Fang.

Detained in 2012, Fang became ‘the most enthusiastic artist that Campsfield would ever have’, according to the institution’s newsletter. Profiled in a document produced for internal circulation only, Fang was asked about how he saw his future with his artistic skills from art school in China. ‘I would like to do better in future to improve my current skill if I have the opportunity here in the UK’,8 he replied. We were permitted to copy the interview for our collection, on the condition that we taped over the photograph of the artist himself.

Fang painted the Queen and Prince Charles, before turning to Prime Minister David Cameron. He sent them their portraits with a letter setting out his case for British citizenship. Perceiving that horse portraits also appealed to the ruling classes, he painted horse heads for good measure. His works have the photorealism of press photographs and the brilliant authenticity of a perfected mimicry. His skills, we were told, were acquired from working in China as a counterfeiter.

As a recent conference on Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting stated, although the visual impact of counterfeits contrasts with their negative connotation, they are still considered as fraud, faken – shadows of a creative act. There is a great irony, hence, in using photorealism to prove the artistry and authenticity necessary to be a skilled economic migrant. Yet forgeries can also be an ‘embodiment of an aesthetic patriotism’, and Fang’s portraits can be read as interpretations of the press photographs on which he based his paintings.9 In his images, the establishment show the harsh public face presented to the press. It is the dignified, official icon of the queen that Fang chooses to represent, not the paparazzi’s scoop of her eating from plastic Tupperware in private. She is a decorated and upright figurehead, with the raised eyebrow of a judge in action. Like many others in detention, Fang assumed she has power in the UK, the way a hierarchical figurehead might. Of course, he was mistaken.

3. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Boardroom of Campsfield House, 2016, digital photograph on poster, 84 x 118 cm, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

3. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Boardroom of Campsfield House, 2016, digital photograph on poster, 84 x 118 cm, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

Fang’s portraits are not uncontroversial in the detention centre. While the Queen sits proudly in the centre’s boardroom (Fig. 3), David Cameron has been returned, unwanted, to the art room. ‘It was an election year’, we were informed, and like the BBC, if the centre were to hang a portrait of the incumbent, they would have needed to represent the other political parties as well.

This photograph is from a series of posters made by Khadija, with Fang’s letters in parafictional form.10 The text was recreated from interviews about the letters Fang wrote to accompany his paintings (the originals remain with the recipients while the replies were taken by Fang when he was deported). In them, the polite replies from Charles and the Queen are recreated to form a sequence. Apparently, it all ended after Fang sent his portrait and letter to David Cameron. He was never seen again, deported once the gift arrived at number 10.

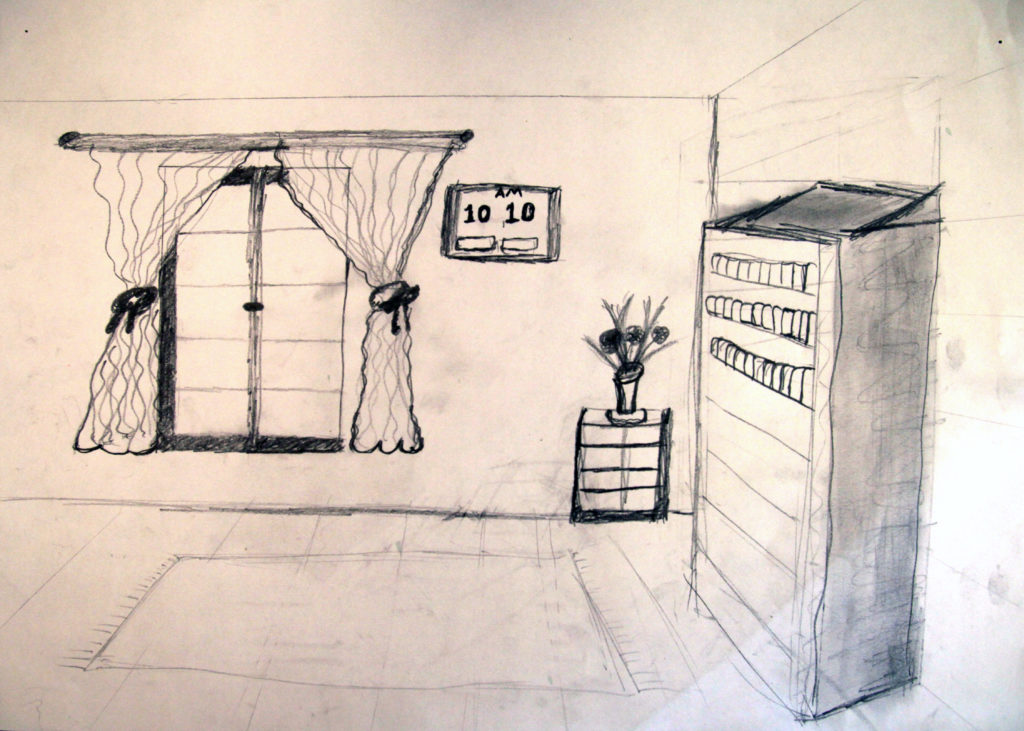

According to the art teacher, many of the men seek to make a perfect, realistic image, and easily become frustrated with the process, failures, and naivety of the drawings they produce. A clear image, a future where there is a sun shining on an English Garden, they will sign (and perhaps more likely take with them from the art room when they leave). What is left in these art rooms are piles of unfinished pictures that have frustrated their makers, or do not fit into their restricted luggage home. Those we watch in their endeavours are almost always producing gifts for their girlfriends and mothers. Their items are included in the digital version of the archive as documentary photographs, while the objects themselves are mailed out or passed over in the visits hall.

During the workshops in Colnbrook IRC, Khadija took portraits of the residents when they requested them, even though she was subsequently unable to share them with the men.11 Images of empty visits halls, or of abandoned objects, exhibit only the biography of material culture that, it has been argued, ‘emerged as a response to the 1980s crisis of representation and the deeper postcolonial critiques that accompanied this crisis’.12 As Severin Fowles has also pointed out, as it became more difficult to study and make claims about non-Western people, anthropologists and scholars in related disciplines began to explore the advantages of treating non-human objects as quasi-human subjects. Things proved safer to study than people and the popularity of ‘thing theory’ grew, at least in part, for this very reason. ‘More importantly, the analytical shift of focus from people to things had the effect of salvaging – and, indeed, greatly amplifying – the representational authority of Western scholars at the precise moment when that authority seemed to be evaporating’.13

The Sites, and the Play Off-Site

External border controls require, generate and reflect internal ones. An IRC is both a site within the nation state and a means of ejecting people from it. For those people crossing borders without documents, the detention centre is always a potential destination, unless they can prove their right to remain.

By creating the archive, we hoped to generate new engagements with these sites of confinement. Documents and artefacts lend themselves to different uses than words and testimonies. The digitisation and projection of them in video literally brings to light otherwise largely invisible objects. While some may stand alone, others need interpretation. In the back and forth between word and image, the images provide an untranslated immediacy for the conceptual frameworks construed in language.

The collection grew in response to the inadequacy of words and arguments. Fieldwork is tiring and emotionally draining. Art promises a more direct emotional response, affective impact on the viewer, and therapy for the maker. Khadija sought to dramatise the experience of being inside in a performative script that obliquely interrogates the system responsible, gesturing to the invisible, inviting people in. This was rehearsed in a pilot video, posters, slide projection, lectures, and then expanded in a play that premiered on December 2, 2016.

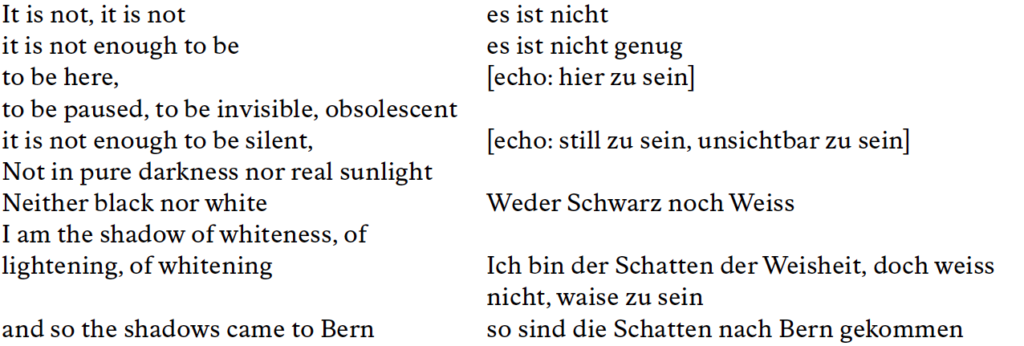

The play, ImIgrazie: In the Shadows, focuses on the feeling of despair in detention, the experience of time and waiting, anger and protest, propaganda and politics. It took these core challenges in the experience of detention, and drew them into a shadow play, enacted by puppets and people, with live music improvised with the enlivenment of the shadowpuppet world. The first scene opens with a haunting Macassar flute, and the last closes with a song Gandrung, a mantra used on the other side of the sea border of Australia before a journey, anticipating arrival and return. The first puppet, a hairy angel, arrives with a poem whispered into it, to bring it to life:

The script is in German, English and Bahasa Indonesian. It had a double premier, in the Konzerttheatre Bern in March 2017, and the Pesta Boneka Fesival in Jogjakarta, following our development of the script with the Swiss writer Jurg Halter and Indonesian composer J. Mo’ong Santoso Pribadi. The cast of puppet characters and the host of instruments were made in Indonesia out of recycled waste materials. Gongs made gas bottles, bagpipes of plumbing offcuts, a biscuit tin sitar, a PVC pipe elephant trunk roaring, flute of plastic waste, toothbrush guitar fret, broken window pane gamelan. These are not visible in In the Shadows, only audible: the recycled waste is a material echo of displaced people, discarded immigration requests.

It was only far from the UK research sites that this play, ImIgrazie: In the Shadows, could begin to develop a response free from the rules set by the residency inside the sites of detention. Shadow puppets have long been used as propaganda imparted to the multilingual masses of the archipelago of Indonesia. For instance, in Indonesian puppetry (Wayang Kulit) during the Soharto regime, there was an hour interval in the epic story that was devoted to propaganda about the dictatorship. It was entertaining and contemporary, different from the classical Ramayana and Mahabharata stories. Until today people stay to watch the performances late into the night, in order to see the favourite part of some, this interval. This part is called Goro Goro, and is the genre that ImIgrazie: In the Shadows conceptually mimicked.

Border studies have been accused, particularly from those within critical race studies, of producing a pornography of misery. There is a danger, not only to us, but also to the agency of those inside, of contributing never-ending stories of woe. Images and artefacts can open a different kind of story, one that abstracts and thereby sharpens the institutional critique in ways that are absorbing and affective. In the Shadows’ final scene, for example, paints a redaction of immigration paperwork in a performative gesture of erasure. Backlit on an overhead projector, my hands turn the bureaucratic form, line by line, to black.

4. Khadija von Zinnenburg Caroll, [Great Britain] – Interview & Highlight Performance, 2016.

Redaction and Pixelation

The intersection of art and criminology of the border makes a contribution to contemporary artistic practises that deal with the aesthetics of redaction, with the censorship of documentary material, like embedded journalism and press reportage of crimes. In so doing, it echoes with works elsewhere. In recent collages, for instance, Thomas Hirschhorn makes ‘pixelation’ into the medium of the faceless crimes of the state, embodied in press coverage. He appropriates these by cut-pasting victims of war, and suturing his juxtapositions with pixels. The lines literally blur between the spectacular and the criminal, the sex and the death that sell commercial photography. But it also refreshes the discourse around agency in the social sciences by asking who has the power to pixelate, and who gets pixelated. In the exaggerated manipulation of images, Hirschhorn can reveal the authority of photographic objectivity and of editorial and political decisions. ‘The time in which we live is a pixelation’, Hirschhorn says, to refer to the faceless abstraction of information as a strategic measure. He historicises pixels to the mid-century abstraction that German fascism categorised as ‘degenerate’ in the work of artists such as Otto Freundlich.14

Hirschhorn’s cutting up of fashion magazines and online reportage is in fact a purely artistic and socially disengaged practise, but it has visual similarities with the necessary redaction of the images in archives such as ours. The Home Office bans photography of recognizable individuals, ‘for their own safety’. As a result, any public use of the portraits we took inside Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre would have to pixelate or black out the face. The infamous Black Square that the Russian Supremacist Kazimir Malevic hung on the site of the Madonna icon is the avant-garde referent for the contemporary aesthetics of redaction. The black squares that stretch into long rectangles on redacted documents and photographs have caught the attention of several artists that work with classified material. They also became important referents for the work we were doing in Oxford, as censorship began to play a part in the way we thought about what was possible, legally and artistically – what was necessary abstraction, and what is necessary documentation.

Sometimes pixelation draws attention to the ‘criminal’ in a standardised way that can be thematised through baroque pixilation, black squares, or indeed through different strategies of visualisation. For the viewer, it is through the censorial pixelation that the crime is made significant: it is factualised in the moment it is redacted. The redaction reads as a validation of the power of a fact, hence it has to be hidden. It may also protect the identities of those locked up, especially those who continue to challenge their asylum status and may, therefore, be vulnerable to the authorities in their country of origin.

The invisibility of immigration detention is a central theme in many of the visual artworks and films on the subject. Virtual Reality has become a technology of visualising detention with heightened immersion of the viewer. The Guardian’s virtual experience 6×9, VR City’s project Invisible, and David Rych’s work Border Act use VR in very different ways to represent incarceration. Rych is interested, as a filmmaker and an activist, in the multiperspectival nature of filming VR that finally removes the one-point perspective of the traditional camera, and turns that into a filming of space. Strapped to the face, empathy is produced also through the physical proximity of the screen wrapped about the head.

Cutting

5. Anonymous, Gentleman’s Club, ca. 2014, design for a mural in Campsfield House IRC, A3, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

5. Anonymous, Gentleman’s Club, ca. 2014, design for a mural in Campsfield House IRC, A3, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford.

The Photoshop cut-paste gets used by detainees to place themselves into the London they migrated to. They have access to two computers, and can purchase a photograph of themselves to send to their family. Photoshop workshops were run also before ours by the photographer Nana Varveropoulou, whose No Mans Land and Life is Good Here reflect on the aesthetics and empowerment of cutting and pasting.15 This practice brings the evidentiary power of the portraits – which the detainees were most keen to produce with us – together with fictions of success, prestige, and security in Britain. The backgrounds, often provided by the art teachers, present fantasy stately homes, Georgian mansions, English gardens, and the image of London’s skyline.

In an art room exercise to produce a design to be painted in trompe-l’oeil on the wall of a common room to ‘cheer it up’, one of the residents won the £5 competition with the design of an English Gentleman’s Club (Fig. 5). The Gentleman’s Club, as with the London skyline, are interpolated into the prison architecture, also for the purpose of selfies (ironically, in a place where no cameras are permitted, because no images of inside are permitted out). Similarly, in the Media Room digital exercises, the selfie and social media conscious population – who are banned from using social media inside – use careful costuming, portraiture and elaborate backgrounds to create an image. Cutting and pasting is the 2D equivalent of migration. It brings the body to an ideal destination. Visually, Photoshop cannot often make this cut realistic. Larger than even the skyscrapers and mansions, the figures hover insistently and, indeed, indeterminately in detention.

6. Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Artists in Residence, 2016.

Conclusion

The immigration detention archive at Oxford and artist residency in Border Criminologies came about through the vision of Mary Bosworth that art could be a form evidence in criminology. There is no disciplinary training in either criminology or art history for using or interpreting the material culture of immigration. Indeed, while there is a small field of ‘visual criminology’, where colleagues analyse images, for the most part criminology is not a visual subject, nor is it one familiar with artistic production. And yet, as this article has shown, art and imagery in criminological analysis of border control have an unexplored cross-disciplinary potential to ask and answer new questions, and to reach new audiences.

The artistic strategies that emerged from Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll’s residency in the IRCs is particular to this collaboration. The access gained, research shared, and emotional responses traced through the process led to an archive and series of artistic responses that would never have come about without immersion in this field site.

While the workshops and dynamics of the institutions put productive limitations on the artist, it taught many important lessons about the real policy impact of public critique, manipulation by the press, the power of paperwork, and the representation of other, vulnerable voices on their behalf. Censorship, abstractions, digital manipulation of documentary photography, virtual reality, and political gift giving gained a new force in the context of immigration removal centres.

The traditionally trained artist is ill equipped to do research in a site such as a prison, charged with social implications that demand to be addressed before ‘art’ can be made. Research itself appears a perversion in the context of human suffering. Yet, our collaboration was of emotional response and intellectual understanding, another border that requires constant negotiation and dismantlement.

1. For more on the ethics and challenges of gaining and maintaining research access to these contested sites, see Mary Bosworth and Blerina Kellezi, ‘Doing Research in Immigration Removal Centres,’ Criminology & Criminal Justice (2016): 1–17. For more of Mary’s work on these institutions see Mary Bosworth, Inside Immigration Detention (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

2. Home Office, ‘Immigration Statistics: October to December 2015,’ London: HMSO (2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-statistics-october-to-december-2015.

3. Home Office, ‘National Statistics Detention,’ London: HMSO (2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-statistics-july-to-september-2016/detention.

4. Mary Bosworth and Marion Vannier, ‘Comparing Immigration Detention in Britain and France: A Matter of Time?’ European Journal of Migration & Law 8:2, (2016): 157-76.

5. Mary Bosworth and Blerina Kellezi, ‘Getting in, Getting Out and Getting Back: Access Ethics and Emotions in Immigration Detention Research,’ in Reflexivity and Criminal Justice: Intersections of Policy, Practice and Research, ed. Sarah Armstrong, Jarret Blaustein and Alistair Henry (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 237–62.

6. Stephen Shaw, ‘Review into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable People,’ London: HMSO (2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/490782/

52532_Shaw_Review_Accessible.pdf.

7. While Campsfield House only holds men, Colnbrook houses a small number of women in a self-contained housing unit within the facility. The women there do not have access to the art room. Instead, they may be provided with items to draw or colour-in upon request.

8. Fang cited (and translated from Chinese) in ‘Interview with an Orderly,’ Campsfield News, Immigration Detention Archive Oxford file, 6.

9. See for instance Tina Öcal, ‘Shape Shifters of Transculturation: Giovanni Bastianini’s Forgeries as Embodiment of an Aesthetic Patriotism,’ Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting, conference paper (Munich, 29–31 October 2015).

10. Carrie Lambert-Beatty, ‘Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility,’ October 129 (2009): 51–84.

11. Just as there is a radio station inside that never broadcasts to the outside world, there are headshots that can never be shared over email.

12. Severin Fowles, ‘The Perfect Subject (Postcolonial Object Studies),’ Journal of Material Culture 21:1 (2016): 9.

13. Idem, 9–27.

14. Thomas Hirschhorn, lecture at the Hamburg Academy of Fine Art (June 2016). For examples of these images see https://www.crousel.com/home/exhibition/600/.

15. See: http://www.nanav.com/album/no-man-s-land.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) / ERC grant agreement n°313362.